By Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

She was a Hindu princess. Streena was one of the brightest students in my graduate school psychology class. We were a class of 12, and she and I were the only ones who actively practiced our faith.

In the afternoons, when it was time for the Mincha service, I would usually slip away to a small synagogue not far from the campus to daven. But there were times when instead I would make use of a small side room and pray in private. It was during one of those times that I discovered that I was not the only one to use that side room for prayers. Streena was there too.

The first time I noticed her there, I spotted her in the far corner of the room deep in prayer. She held a small object in her hand. I inquired about it and she showed me what looked like a small doll, only she referred to it by a Hindu name that meant that it was her deity, her God. Plainly and simply, it was an idol.

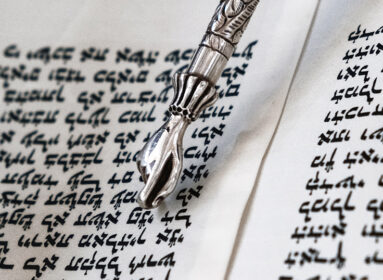

I told her that when I as a Jew prayed, I did not pray to any image, statue or portrait. I prayed to an invisible and unknowable God. She found that impossible to accept. “When I pray,” she insisted, “I must have some concrete visual image before me.”

The stark contrast between Streena’s mode of prayer and my Jewish conception of the way in which we are to conceive the Almighty is one of the lessons of the Golden Calf.

Moses ascends the mountain to receive the holy tablets. He is delayed in his return, and, in their impatience, the Jewish people collect gold, fashion an idol out of it in the shape of a calf, and worship it with sacrifices and an orgiastic feast. The sudden descent of the people from a state of lofty spiritual anticipation to the degrading scene of dancing worshipfully before a graven image confounded the king of the Khazars, a nation in Central Asia, whose search for religious truth is the theme of one of the most intriguing books of Jewish philosophy, Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi’s Kuzari. In the king’s dialogue with the Jewish sage who is his spiritual mentor, he condemns this behavior and challenges the sage to justify the apparent idolatry of the Jewish people. The sage, who is actually the voice of the author of the Kuzari, responds, in part: “In those days, every people worshiped images… This is because they would focus their attention upon the image, and profess to the masses that divinity attaches itself to the image… We do something like this today when we treat certain places with special reverence – we will even consider the soil and rocks of these places as sources of blessing… The objective was to have some tangible item that they could focus upon… Their intent was not to deny the God who took them out of Egypt; rather, it was to have something in front of them upon which they could concentrate when recounting God’s wonders…”

This is but one explanation of the motivation for what is one of the greatest recorded sins of our people. But it is an especially instructive explanation.

In our own inner experiences of prayer, we have all struggled with the difficulty of addressing an abstract, invisible, and unknowable deity. It is comforting to imagine that we stand before a mortal king, or a flesh and blood father figure, someone physical and real.

But we believe in a deity who sees but is not seen, hears but is not heard, and who is as far from human ken as heaven is from Earth. In this fundamental belief, we differ from many other religions.

Nevertheless, we can sympathize with Streena’s need to pray to her doll, and in the process we can come to grips with what must have been going on in the minds of our ancestors when they stooped to idolatry and committed the sin which the Almighty has never totally forgiven, the worship of the Golden Calf.

Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Weinreb is the executive vice president, emeritus of the Orthodox Union.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger