By Menachem Wecker

(JNS) Until recently, French Impressionism was a Cinderella story. Derided in the late 19th century and excluded from the French academy (Salon), Impressionism—whose name derives from a critic’s mockery—became one of the most beloved art movements.

Impressionist sections are among the most trafficked in art museums, whose gift shops hawk umbrellas, tote bags, ballpoint pens and other accessories decorated with works by Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro and others. Those artists’ fortunes rose so much that it became a mark of academic connoisseurship to scorn the popular movement as too pretty and superficial.

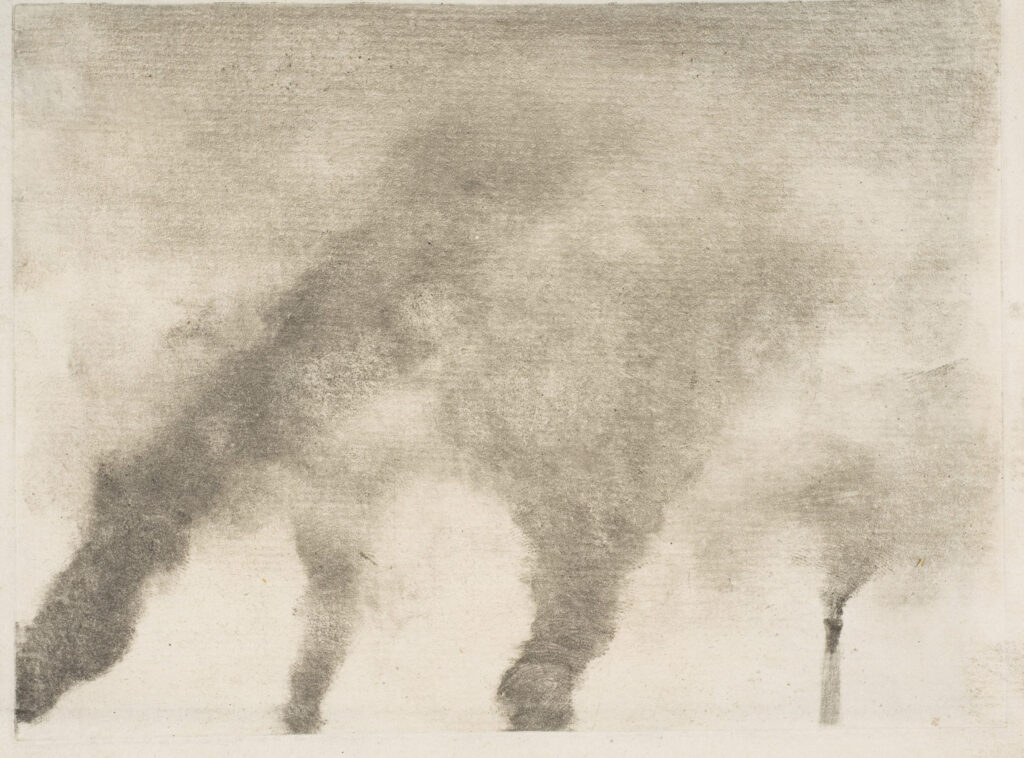

In recent years, Impressionism’s reputation has changed again. Museums often discuss not the pretty colors in Impressionist skies, but the way pollution made a Monet sunset look the way it does. They also include a call to arms for climate-change activism.

Writing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in December 2022, Anna Lea Albright of the Sorbonne University in Paris and Peter Huybers of Harvard University in Massachusetts studied the connection between industrialization, atmospheric changes and the painting styles of British artist Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) and French painter Monet (1840-1926).

“Our basic premise is that Impressionism—as developed in the works of Turner, Monet and others—contains elements of polluted realism. Over the 19th century, the atmospheric reality in London and Paris changed,” they concluded. “Turner, Monet and others document these changes in paint, yielding proxy evidence for historical trends in atmospheric pollution before instrumental measurements of air pollution become available.”

The Seattle Art Museum refers in a blog post to the “terrible pollution” that “created a very foggy atmosphere,” which Monet captured.

Describing Monet’s “Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect” (1903), the Denver Art Museum observes that “smog was like a veil over the city that changed colors with the light. Most people thought it quite dirty, smelly and disgusting, but Monet found it wonderful.”

Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario has mentioned pollution in wall labels that describe two Impressionist paintings in its collection. Pissarro “saw this scene as a celebration of the progress and productivity of French industry, largely unaware of the pollution that we might see today,” it notes of “Pont Boieldieu in Rouen, Damp Weather” (1896). Of Monet’s “Charing Cross Bridge, Fog” (1902), the museum adds, “Has pollution ever looked so beautiful?”

The Brooklyn Museum website tags Monet’s “Houses of Parliament, Sunlight Effect” (1903) and George Inness’s “Sunrise” (1887) with “pollution” and “smog.” It uses the “pollution” tag for Charles-François Daubigny’s “The River Seine at Mantes” (1856).

The National Gallery of Art’s website reflected on “Painting Climate Change in the 17th Century” in a blog post. “While we should urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions to minimize the eventual magnitude of global warming, we now have little choice but to adapt to a hotter and more extreme climate. We can find inspiration, and perhaps some reassurance, in 17th-century Dutch history and art,” Dagomar Degroot, associate professor of environmental history at Georgetown University, concluded in the post.

“But we must also remember the cost of Dutch successes. Climate adaptation must be just. It must reduce inequality, rather than exacerbate it. If it does, artists may yet paint hopeful vistas of our hotter future,” added Degroot. (Another National Gallery blog post shares “Five Artworks for Talking about Climate Change.”)

“This is not art history. It’s more like searching for contemporary relevance with a divining rod. It’s cloudy with a chance of meatballs,” James Panero, an art critic and executive editor of The New Criterion, told JNS.

Diana Furchtgott‑Roth, director of the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Energy, Climate and Environment, and fellow in energy and environmental policy, told JNS that Impressionist paintings are the opposite of climate-change cautionary illustrations.

“The air has indeed gotten much cleaner since the 19th century. As societies get better off, people demand—and society can afford—cleaner air,” she said. “With clean natural gas and unleaded gas, America has dramatically reduced air pollution.”

Not only does U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data from the past 20 years show that air is getting cleaner, but it has “vastly improved since the late 1800s, early 1900s, when coal was used for electricity generation and there were no scrubbers to clean up the particulates,” said Furchtgott‑Roth.

“So we can look at these paintings and say things are much improved,” she added.

As museums flag smog in the background of Impressionist landscapes, it is exceedingly rare that they address another timely subject, antisemitism, which plagued the Impressionists and which is reportedly surging currently.

Most museums identify Pissarro as Camille Pissarro, rather than with his given name Jacob-Abraham-Camille Pissarro. When they explain Pissarro’s biography, very few museums note that he was Jewish, and it is very rare for museums to share that Degas was virulently antisemitic.

In one of many antisemitic letters, some translated for the first time in Theodore Reff’s “The Letters of Edgar Degas” (2020), Degas wrote to a close friend in 1901 about the passing of retired military officer Édouard Lippmann, ostensibly a friend.

“So he is gone, the poor Wandering Jew. He will no longer be walking, and if we had been forewarned, we would have walked a little behind him. What did he think since the dirty Affair began?” wrote Degas of the Dreyfus Affair, referring to French Jewish Capt. Alfred Dreyfus, and his arrest in 1894 and sentence on false grounds of treason. (He was exonerated in 1906 and reinstated into the French army).

“What did he think of the awkwardness one felt with him, in spite of oneself?” Degas continued in the letter. “What was going on in his old Israelite head? Did he even think back to the time when we more or less overlooked his terrible race?”

Degas and Pissarro famously broke off their friendship over the affair, and Degas did not go to Pissarro’s funeral. Pissarro also wrote several times about Jewish subjects to his son Lucien, including when the latter was engaged to a Jewish woman, whose family was more observant than the Pissarros.

If museum officials believe that it is not shouldering too much responsibility to place the burden on their displays of improving major problems outside their walls, like climate change, presumably they could dispatch their collections, programs and exhibitions to tackle antisemitism, too.

Larry Silver, professor emeritus of art history at the University of Pennsylvania and author of many books and articles on Jewish art, including (with Samantha Baskind) “Jewish Art: A Modern History” (2011), told JNS that questions about the museological approach of bringing contemporary concerns into curation “touched a nerve.”

“I guess I should not be surprised that Jewish identity is obscured as a topic now since other identities are more important,” he said. “What if Pissarro was gay instead? Or perhaps his Caribbean origins might matter more to some commentators.”

Pollution might play a role in Impressionist works, including the poster child of the movement—Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise” (1872)—“but surely it is not a central issue or one that the artist deliberately singled out, even if his current observers now see that element anew,” said Silver.

As to museums educating the public about the Dreyfus Affair, “that is history, and today’s critics and students seem to be ‘presentists,’ ” or very focused on the contemporary moment, said Silver. He thinks a bit of history, including about the Holocaust, would help students.

“Obviously, I care that Pissarro was Jewish, albeit with a lot of self-hatred about that fact and a common-law Catholic French wife, but I am not sure that this is the most important thing about him either, except when such nuances are taken into account,” he added. “And as an anarchist, he bitterly satirized the Rothschilds.”

MAIN PHOTO: British “Houses of Parliament, Sunlight Effect” (1903) by Claude Monet. Credit: Brooklyn Museum, N.Y.’

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger