By Menachem Wecker

(JNS) One of history’s great literary revisionism discussions ensues when Moses and God converse after the Golden Calf fiasco. If God does not forgive the Israelites, “Erase me, now, from the book You wrote,” Moses says. In Exodus 32:34, God answers, “He who sinned against me I will erase from My book.”

Erasing people as punishment for their bad behavior has an extended history, from the Egyptian ruler Akhenaten (14th century BCE) erasing his predecessors from temples (and whose successors, in turn, erased him) to the Roman Senate’s damnatio memoriae—literally striking people from the historical record.

There have been many instances since, though the latest iteration surrounds the literature of British novelist, poet and screenwriter Roald Dahl (1916-90), probably best known for his children’s books.

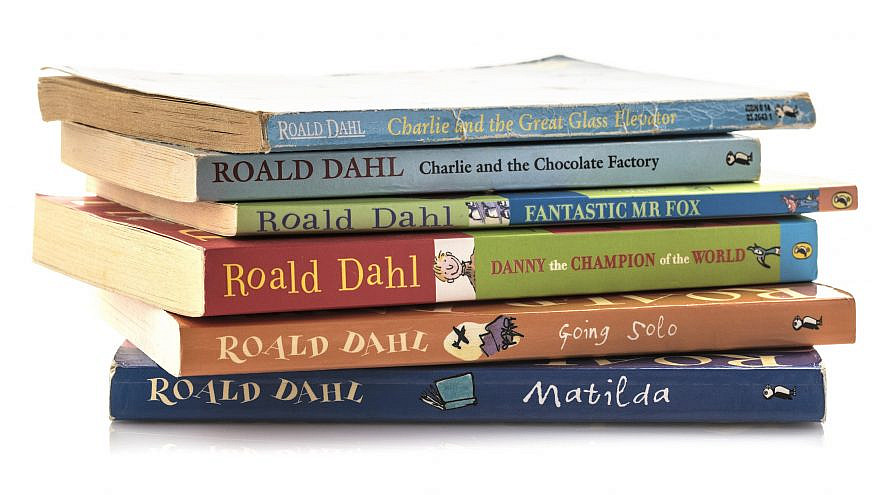

Many grew up or are growing up with Dahl’s books, such as James and the Giant Peach (1961), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964), The BFG (1982), The Witches (1983) and Matilda (1988). Several have been made into popular films. But the other side to Dahl was an openly anti-Israel and antisemitic writer of vivid prose.

“There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity,” Dahl once said, adding “even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.”

He claimed that Jewish publishers “control the media” and said, “I’m certainly anti-Israeli, and I’ve become antisemitic in as much as that you get a Jewish person in another country like England strongly supporting Zionism.”

The degree to which writers can be separated from their writings is subject to dispute. Penguin Random House’s Puffin Books has altered hundreds of words in the Dahl books it publishes, reports The Telegraph. Among the changes, per the London paper, are “Cloud-People” replacing “Cloud-Men,” and changing a reference from Rudyard Kipling to Jane Austen.

Elsewhere, “mothers and fathers” becomes “parents,” “maid” morphs into “cleaner,” and “red in the face” is rendered “hot under the collar.”

“It’s Roald Dahl, but different,” The Telegraph reports.

“These edits aren’t to passages that most readers would deem racist or misogynistic. Many of the edits are intended to bring the novels in line with DEI-approved views about gender and sex differences that are not mainstream,” Christopher Scalia, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who studies culture, told JNS. (DEI is diversity, equity and inclusion.)

The changes aren’t just a word here or there. “In many cases, significant passages are either removed or replaced. The quality of the writing suffers as a result—and in at least one case, the very moral of the novel changes, too,” said Scalia.

Those who would be offended by a character described as “fat” or “thin” (Puffin changed both) “are unlikely to like much else about Dahl’s very dark humor,” according to Scalia. “It’s enough to make you wish the people behind this decision suffer the fates of Veruca Salt or Augustus Gloop.” (In Dahl’s book, the former goes down a garbage chute, and the latter is squeezed through a pipe.)

’Bizarre to put words in his mouth’

Emily Jashinsky, culture editor at The Federalist and host of Federalist Radio Hour, told JNS that Dahl edited his books, including “Charlie,” to reflect better values. “Those changes were made in his own words,” she said. “Since he’s long gone, it’s bizarre to change historical documents and put words into his mouth.”

“Old art is old art. It often ages poorly, and healthy cultures are able to grapple with that without sweeping it under the rug, which makes it hard for us to appreciate our progress, because we lose points of reference,” she said. She called many of Puffin’s changes “excessively, laughably sensitive.”

Jashinsky notes an “Apology for antisemitic comments made by Roald Dahl,” issued by the Dahl family and the Roald Dahl Story Company. “It’s a part of him, and it’s a part of reading his work, like his awful depictions of race,” she said. “These are difficult subjects to address with children, his primary audience, but they also offer good and necessary lessons in how our culture has evolved.”

“It’s absolutely reasonable to acknowledge that so long as it’s done more with substance than performative groveling,” she said.

Not wanting to patronize living artists, who use their profits and reputation for evil, makes sense, according to Jashinsky, but she doesn’t understand avoiding the art of bad people because it could reflect their values. “Of course, it does,” she said. “We don’t read books to nod and turn the page. We read books to enter another person’s world for the purpose of entertainment and enlightenment.”

’Every artist falls prey to blind spots’

Karen Swallow Prior, research professor of English, and Christianity and culture, at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, N.C., sees things somewhat differently. Classical literary works are abridged and translated all the time, “even the Bible,” she told JNS.

“To alter language in such a way that it erases the history of its own context is to erase the work of art itself. Either the work of art passes the test of time, or it does not,” she said. “The audience ought to decide and will be no worse, but better, for doing so.”

Swallow Prior sees Dahl’s works as an in-between category, which passes the test of time for some revered qualities, but for which “the passage of time reveals the moral or aesthetic blind spots of the artist and his or her times.”

“Good art can definitely happen to bad people. Art history is replete with artists who lived reprehensible lives and produced great art. We ought not to ignore this or excuse such failings,” she said. “It is preferable to assign a work or artist to the dustbin of history, if such is deserved, than to soften or cover up what an artist got wrong. Doing so only makes us more susceptible to falling naively for the same errors.”

When an artist depicts harmful or incorrect imagery or ideas, readers ought to recognize that harm, or wrong, along with the good, she said. And looking back at past works also gives artists pause today about how future critics might judge them based on yet-unclear norms.

“One of the great gifts literature of the past offers us is the humble reminder that every age and every artist falls prey to blind spots,” said Swallow Prior. “We are no exception, and we must be mindful of that with every work of art we encounter and every artist we are tempted to revere.”

’Don’t know how our shared values will bend’

Michael Weingrad, professor of Judaic studies at Portland State University, told JNS that Puffin’s decision to “edit” the books “is an unconscionable violation of faithfulness to the written word—to any words and not just Dahl’s.” The decision is a “cuddly version” of George Orwell’s “1984,” in which bureaucrats constantly rewrite works “to conform to whatever the ruling authorities decree to be acceptable at the moment,” Weingrad said. “No one knows anymore what is real.”

Readers, rather than “faceless apparatchiks,” should decide which books are good and bad, according to Weingrad.

When Weingrad’s children were young, their elementary school inaugurated an annual celebration of Dahl’s birthday on Sept. 13. He figured the principal and teachers were unaware that Roald Dahl Day was celebrating such a “personally vile” writer who was an “open antisemite and general creep.” They were embarrassed when he alerted them, and they stopped celebrating the day.

“I was emphatic in my communications with the school that I think Dahl’s books should absolutely be read, and the teachers should keep assigning them,” Weingrad told JNS. “We don’t need to create a new birthday celebration for an antisemite, but neither do we need to cordon off his books.”

“The last thing we should be doing in 21st-century America is censoring books based on categories of judgment that were often invented a few years ago,” he added. “The people doing this have no idea what they don’t know and no sense of a literary or cultural or moral tradition that extends back before their own lifetimes.”

Jashinsky of The Federalist said that many think of the future as a moral arc, bending towards justice. “The truth is that we really don’t know how our shared values will bend,” she said. “But if we all create a culture that rewards artists who uphold human dignity, we’ll all help create a better incentive structure.”

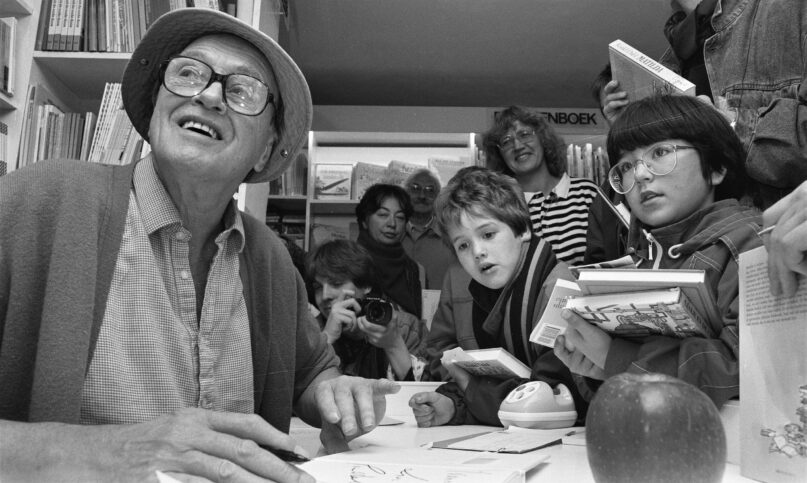

Main Photo: Roald Dahl signs books for children in Amsterdam on Oct. 12, 1988. Credit: Rob Bogaerts/Anefo via Wikimedia Commons.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger