By Stacey Dresner

WEST HARTFORD – Sharone Kornman was only 26 years old and new to West Hartford in 1990 when she first attended a meeting of the Hartford Holocaust Commemoration Committee.

“I didn’t know anybody but I knew someone through a family connection and she said you should come to this Holocaust commemoration committee meeting at the JCC,” recalled Kornman, who New Jersey native whose parents were both Holocaust survivors.

“Most everybody in the room was a survivor. I was really young and I wasn’t from here… The few 2G’s [Second Generation’s] in the room were in their 40s. And there were a lot of strong personalities – people with a certain way of wanting to do things.”

As a young newcomer – and perceived as a bit of an outsider – Kornman says she found the meetings to be a bit difficult, but she kept attending.

“I didn’t go because it was fun or a good way to meet people. I went because this was something I felt I had to do,” she says.

Kornman has not only stayed involved in the planning of the annual Holocaust commemoration in West Hartford for the past 30 years, but she is a founding member of Voices of Hope, the non-profit educational organization created by descendants of Holocaust survivors from across Connecticut.

Kornman will be Voices of Hope’s L’Dor V’Dor honoree at this year’s Evening of Hope fundraiser, “Celebrating 13 Years: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow,” on Nov. 17. The virtual event will be on YouTube Live at 7 p.m.

“Sharone is amazing. She is constantly brainstorming about how to engage people and how to get Voices of Hope out into the community,” said Adele Jacobs, a Voices of Hope board member and daughter of the Fred Jacobs z”l, a Holocaust survivor and longtime committee chair of the Hartford Holocaust Commemoration Committee. “She is an integral part of Voices of Hope.”

Second Generation

Kornman says that she just always knew her parents were Holocaust survivors.

“There is not a moment. There’s not a big reveal…you just know that about them,” Kornman said. “But I did not fully know the details. There was sadness, but they did not transpose that kind of trauma on us, which I know happened in other families.”

Growing up in Teaneck, New Jersey, her parents, Irene and Eugene Frisch who were both from towns in Poland that are now a part of Ukraine – had a group of friends who were also survivors from Poland and considered one another family.

Irene had only been 11 when the Nazis invaded her town of Drohobycz, Poland. It was the young Catholic Polish woman named Fania who was the nanny of Frisch and her two older siblings who ended up saving their lives.

When the war began, Frania had to leave the family because non-Jewish Poles were not allowed to work for Jews. Irene’s family was moved into the ghetto when she was 11. When Irene’s mother heard of a particular “Aktion” – a Nazi campaign rounding up and killing Jews in the ghetto – Irene’s mother knew that she needed to do something to protect her young daughter.

“During these Aktions they went after children and old people,” Kornman explained.

On Christmas eve 1942, Frania arrived at the ghetto knowing that the guards would be drunk and less watchful. She slipped Irene out of the ghetto and into her tiny apartment, where the little girl hid under a bed. After a few months, Irene’s mother and sister also made it to the apartment where they stayed hidden until they were liberated by the Russians near the end of 1944. Irene’s father had been hiding in the woods until he was captured. He spent time in several concentration camps before being liberated.

After spending time in Israel and then back in German, Irene followed her older sister, Pola, to the U.S. in 1961. It was Pola who fixed her sister up with a nice young man she had met in Israel, named Eugene Frisch.

Eugene was born and raised in Kolomyea, a more rural town in Poland near the base of the Carpathian Mountains. (His paternal grandparents were early Zionists who made aliyah to Israel in the 1920s). The Nazis invaded just after Eugene finished his first year in college. He tried to get home to his family, but could only get on a train Russia where he ended up in a work camp. He lost his mother and brother during the war.

“He didn’t talk very much about these things and we didn’t really know very much,” Kornman said.

After spending time in a displaced person camp in Italy after the war, Eugene went to Israel, then the U.S.

Three months after the two went out on a blind date, Irene and Eugene were married. They raised Sharone and her younger brother in Teaneck.

Kornman said that she was already an adult and married when her mother wrote her first story about her wartime experiences.

“Something possessed her to start writing and I can’t tell you what it was. But she sent the story into the New York Daily News and they published it on page 4,” Kornman said. “That really whet her appetite, so then she started to write a lot of stories. Later on, she would go and speak at schools after she retired.”

Irene’s stories have appeared in the Connecticut Jewish Ledger, Lilith Magazine, The Jewish Standard and several books.

Irene moved to West Hartford several years ago. By then, Kornman was ensconced in the West Hartford community with her husband Paul and their three children, Jacob, Israel, and Joseph. Kornman has practiced law in Hartford for 30 years. She and her family are members of The Emanuel Synagogue.

She has remained active in the Hartford Holocaust Commemoration Committee.

“I kept going because I felt an obligation, and eventually more 2G’s showed up. Some of the survivors passed away, or moved to Florida – some of them were just tired. Basically the 2G’s became more active.”

Thirteen years ago at a Holocaust Commemoration at the Connecticut State Capital, Alan Lazowski – son of survivors Rabbi Philip and Ruth Lazowski and owner of LAZ Parking – came up with the idea to form an organization of the second generation and families of survivors that would promote Holocaust education and remembrance. That was the beginning of Voices of Hope.

“The initial charge of the organization was to prepare us to tell our parents’ stories when they weren’t around anymore,” Kornman said.

Today, besides that important duty, Voices of Hope provides community outreach; Holocaust-themed films, art exhibits and book discussions; educator workshops, webinars and museum trips; scholarships and grants; curriculum and resources of educators; and organizes school speaking engagements with survivors.

And now, besides telling their parents’ stories, VOH members are working to tell their own stories as 2Gs. Kornman and other descendants have been trained via the Hartford organization “Speak Up” which holds workshops to help people craft their own stories for the stage. Kornman’s story was about her and her mother’s first trip back to Irene’s hometown.

“I was in the first grouping of that and it was very exciting to be part of that. That was where we really kind of learned that we have a story – the moment where I learned it is not my job to tell my mother’s story; that’s her story. My job is to tell my story, but when I tell it you should also learning something about my mother’s story.”

Kornman was also involved in Voices of Hope’s first conference for descendents, held at the University of Hartford in February of 2018.

“She was one of the co-chairs of the conference that we hoped would be an annual event. It was hugely successful, but it has been derailed by Covid,” Adele Jacobs said. “Sharone was also the idea person for the 2G Book Club. And she was also one of the idea people for the virtual speaker series that we’ve had consistently almost every month since Covid started. She kept us kind of in people’s faces, getting authors and speakers. She made it incredibly interactive and engaging.”

This year Jacobs is presenting the L’Dor V’Dor award to Kornman at the Evening of Hope, started several years ago to raise funds for VOH and to highlight the organization and its members.

“In my speech I describe Sharone as a force of nature,” Jacobs said “Voices of Hope wouldn’t be what it is today without Sharone.”

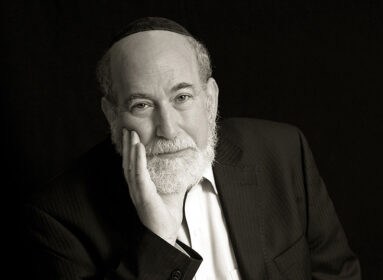

Main Photo: Sharone Kornman in front of a treasured framed display of photos of her parents lives during and after World War II.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger