By Bob Liftig

I was born just after World War II, on the cusp of a new generation. I am now one of the few who, in fact and in distant memory, was held in the arms of my immigrant great grandparents.

Today, when those who want to flatter me try, they call me “The Family Historian.”

My great-grandparents, grandparents, and my parents are long since buried.

Like a tombstone, I remain to tell their stories.

Sometimes I get calls from the sixth or seventh generation of related Jews in America who are – choose one: part Irish or Scandinavian orb Italian or part “other.” These kids almost always need help on extra credit projects – especially related to their genealogy. They almost never call out of a personal passion for family history.

The conversation usually goes like this:

“The only family I haven’t traced is yours. I’ve already been to County Cork and seen our family castle. I took a side trip to Greenland and sat in a 1,000 -year-old sauna – the one my ancestor, Eric the Red, used before he discovered America. Then, I did the whole Scottish thing. I even went to the Games up in Edinburgh and met the chief of Clan McDonald. But all he wanted to talk about was how the Campbells massacred his family in 1692. Who cares? Boring! So, I told him my Mom is part Campbell; and he wouldn’t talk to me anymore! All I have left is your family. What can you tell me about the Bernsteins?”

“I think you mean ‘Greensteins.’”

“Whatever. Did they do anything famous?”

Kids’ attention spans are short these days, so I have to pick and choose which ancestor to tell them about.

I decide to talk about my great-grandfather, Sam Greenstein, of Spring Street, New Britain, in the 1890s, who lived long enough to hold me in his arms.

“Sam was known in the family as: ‘The Fisherman’; ‘The Greatest Storyteller on Earth – But Always Fish Stories,’ ‘The Funniest Fisherman in New Britain – But He Only Joked About Fish,’ ‘The Man Who Never Made A Lot of Money Because All He Ever Did Was Fish.”

Sam died in 1949, age 91, when I was two. He fell through a hole he cut in the ice of his favorite pond in the dead of a Massachusetts winter, and wasn’t seen again until March – when the ice broke. He had been living with his daughter in Agawam. He left two fish near his ice-fishing hole – Sam Greenstein’s last gift to his family.

That’s how the story was told to me, anyway, and that’s how I tell it.

I often sense at this point I am about to lose the attention of my great-great grand- nephew, or my second cousin three times removed, so I bear down hard on the facts.

“Sam was born in 1858 in Vilna, Lithuania, but was actually a latecomer to America. His Uncle Ben had come to New Britain first – in 1882 – practically on the Jewish Mayflower; and had set up shop as a kosher butcher. He was soon described in the local papers as ‘a businessman of this city.’

This was a big accomplishment.

Ben brought his 20-year-old daughter, Anna, with him, but she went back to Lithuania in 1884, because she “didn’t like it here.” Back in Vilna, she married her first cousin, Sam; and, in 1886, gave birth to their first son, my grandfather, Dr. Charles Jacob Greenstein.”

Something in all of this usually stirs some interest.

“Yes,” I say. “A lot immigrants DID go back because it was so different over here.”

And.

“Yes. It was accepted in those days to marry your first cousin. It was even something your parents WANTED you to do.”

When I hear, “Yuck!” on the other end, I know I’ve hooked them.

“Sam and Anna and their son Charlie didn’t get to this country until 1890 – when Sam was 32, Anna, 28, and Charlie, 4. Can you imagine all the changes they had to make? They had been used to another way of life, another government, another set of circumstances, another language!”

“Why didn’t they speak English like everybody else in the world?”

“Sam was a clockmaker, like his father; and Old Sam’s father, another Ben, who must have been born in the 1830s, was ‘The Official Watchmaker To The Czar of Russia!”

“What’s a watch? What’s a Czar? Where’s Russia? Were they hackers?”

“Ben must have worked for Czar Alexander II, who was known as ‘one the best friends the Jews of Russia every had’ – which, trust me, didn’t mean very much. An assassin threw a bomb, and that was the end of Ben’s boss. Only one Jew was even vaguely implicated, but the the Jews were blamed anyway, and the locals beat them up, looted all their businesses, and a lot of Lithuanian Jews left for America – including Ben.”

“What’s a ‘Jew’?”

“This happened in 1881. One year later, Uncle Ben, set up a kosher butcher shop in New Britain. Imagine how bad things must have been in Lithuania for Ben to pull up stakes, put his family on a steam ship, and travel 4,000 miles to get to a country he had never seen before. But, Ben got a foothold here in a wonderful new country and his daughter Anna and her husband Sam and their son Charlie joined him here. It was a good move because in Lithuania they were starving.”

“What’s ‘starving’?”

“There was a really bad depression going on in America in 1893; but the Greensteins managed to keep their shops going. Sam and Anna raised five children. All but his pretty daughter, Sadie, went to law or medical schools. One son became the District Attorney for Hartford County; another son became a judge in Norwich; and my grandfather was a doctor in New Britain for almost 60 years. They knew more prosperity than any other Greensteins knew in 2,000 years. And, when the brothers were drafted into World War I, they became Army officers! In Lithuania, they would have just been cannon fodder.”

“What’s ‘drafted’?”

“The kids never forgot their parents, and supported them the rest of their lives. Even after Anna died in 1934, Sam didn’t have to live alone in some cheap apartment. He moved in with his daughter Sadie in Massachusetts. She took care of him until the day he died, at the incredibly old age of 91.”

“Only 91?”

“Sam never forgot his Jewish heritage. In 1898, he established one of the first synagogues in New Britain – Beth Alom. He must have been very smart too, because he could speak and write in several languages, and he read the American newspapers every morning.”

“What’s a newspaper?”

“Sam was known as a terrific fisherman! And a wonderful storyteller. And a really skilled craftsman. We have one of his wall clocks, and it still keeps perfect time. Sam was a gentle man. He saw a lot of hard times, but he never gave up. He never gave in. He used his sense of humor to get through it. When he became an American in 1897, he was so happy, he danced a jig!”

“What’s a sense of humor?”

“But of all the wonderful things Sam did for his family, his biggest accomplishment was getting them out of Lithuania and getting them to the USA, so that his kids wouldn’t have to suffer. So that they could have a better life. Sam made a lot of sacrifices, and even though he didn’t know it at the time, he sacrificed for you.”

“Is this over yet?”

“Wait! I want you to say that, if Sam hadn’t been brave enough to take all the chances he had to take, you wouldn’t be here today; because Sam and his family, and a lot of your cousins, would have been killed in the Holocaust.”

“What’s the Holocaust?”

“Sam was an American Hero. You should be proud to say that Sam was your ancestor. He was grateful to become an American – and you should be proud to tell his story to everyone.”

“What’s an ‘American Hero’? I didn’t know we had any.”

“Good-bye now. I’m going to go to bed. Hugs to your mom and dad, and to your grandparents.”

Dr. Robert A. Liftig is an adjunct professor of ethics at Fairfield University and a freelance writer. He lives in Westport.

Readers are invited to submit original work on a topic of their choosing to Kolot. Submissions should be sent to judiej@jewishledger.com.

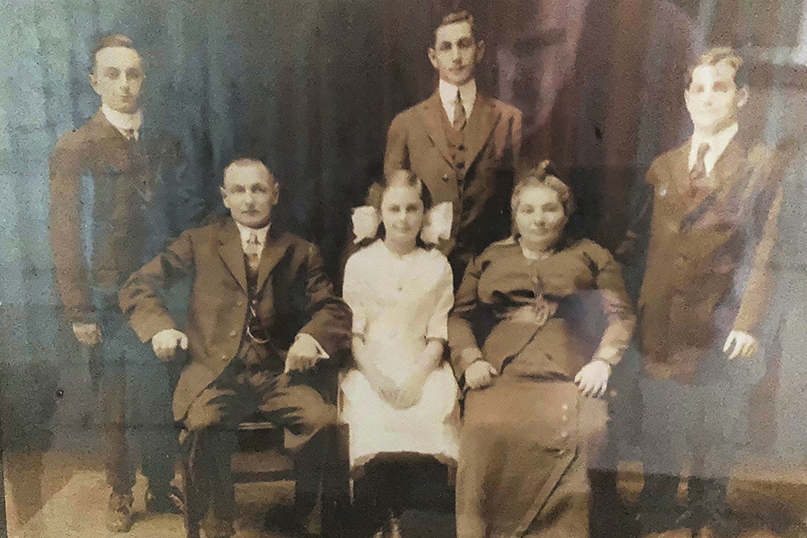

Main Photo: Members of Bob Liftig’s Greenstein family in an undated photo.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger