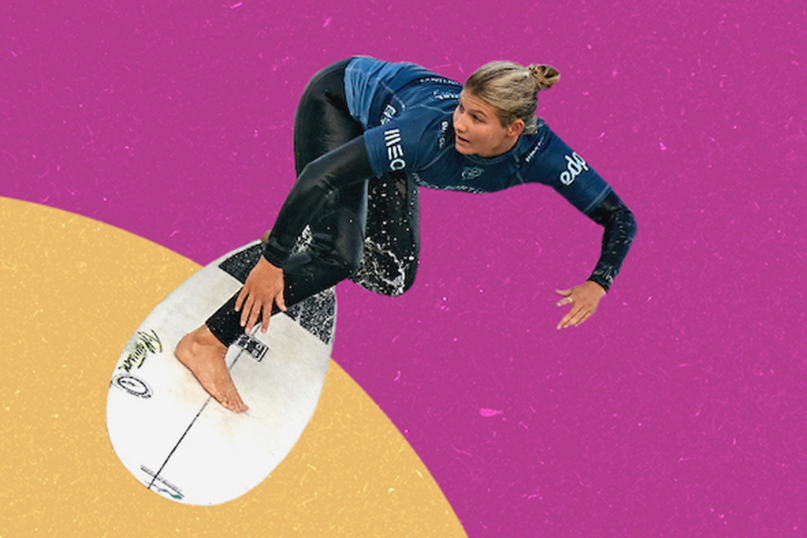

Israeli surfer Anat Lelior’s unlikely path to the Tokyo Olympics

By Anna Dimond

Anat Lelior’s first experience with surfing came at age five.

It was an inauspicious start to the sport that would become her career and, later this month, take her to the Tokyo Olympics.

Her father, Yochai, lay on the back of the board with her at their local beach in Tel Aviv and pushed both of them into a breaking wave. But instead of riding to the sand triumphant, the board nosedived. They tumbled off and the board shot into the air like an 8-foot, plastic-and-foam projectile. On its return trip it hit Anat on the forehead, splitting it open.

As blood ran down his daughter’s face, Yochai recalled, “all the people on the beach were looking at me like I was a murderer.”

Anat, however, was unfazed. After dripping blood across the sand and getting stitches at the hospital, she asked to go back to the beach. When Yochai took her back to the scene of the crime, the lifeguards there made her tea and she sat, stitched up and bandaged, watching the waves.

Despite her injury, it was the beginning of Anat’s love affair with the sport. She continued to surf, and eventually began entering regional contests run by the Israeli Surfing Association, or ISA. Soon she was not only winning, but catching the eye of the local surf industry. Artur Rashkovan, the owner of Klinika, a Tel Aviv surf shop and pivotal figure in the Israeli city’s modern surf culture, remembers the first time he saw her surf.

“I was announcing a local kids’ contest in Netanya, around 2007,” he said. “I saw this girl, like 12 years old, and she was laying back [a technical, snapping maneuver] and throwing water. I didn’t know her name and I freaked. I was like, ‘Who is this girl?!’”

That ability to throw water – the amount of spray coming from a board as a surfer turns it – requires strong legs, technical skills and confidence. In Anat’s case, it was just one indication of her power and prowess in the water.

In Israel at the time there were only a handful of other girls competing and Anat quickly ran out of people to surf against. According to Rashkovan, surfer Maya Dauber had come up against the same problem in the 1980s. Known as Israel’s first female pro, Dauber ended up competing against boys due to the lack of female opponents. But by the time Anat began competing and pursuing a surfing career, not only were there fewer kids surfing, but national interest in the sport was all but dead. The barrier to entry had become even higher.

“The European surfers started getting bigger sponsorships and the ASP circuit [the global organizing body] would go to Europe,” Rashkovan said. “There was a geographic connection for them, too, and we were, you know, at the end of the [Mediterranean], left out.”

So the idea of surfing becoming an Olympic sport – much less an Israeli competing in them – seemed more than a little far-fetched.

But in 2002, Rashkovan became the director of the Israeli Surfing Association. He dreamt of the day that Israel had a vibrant surf culture. However, while the industry as a whole was thriving, in Israel, competitive surfing was not.

Rashkovan went to work: He offered insurance and surf shop discounts as perks of membership. He threw a big relaunch party for the association, and brought in the major brands and registered new members. By the time he left the association in the mid-2000s, Rashkovan had reinvigorated competitive surfing, started to rebuild its membership roster and created the first events for girls.

In 2007, he and the ISA passed the reins to Yossi Zamir, an Israel native who had newly returned after nearly two decades living in Australia. Zamir had not only formed close industry connections there, but also saw a highly organized, government-sponsored approach to surfing with competition that created a kind of feeder system to the sport’s upper echelon.

Zamir’s first goal was to get more kids into surfing and put some structure, rules and standards into the competitions. Next up was to bring higher-profile, international qualifying contests to the country. And together with a top Australian coach, Zamir developed a coaching program and high-performance clinics for ISA surfers.

Like Rashkovan, he also remembers his first time seeing Anat surf.

“At the first clinic, Anat arrived with her sister,” Zamir said. “She was really young and we actually saw her potential already at that time.”

It was around 2012, when Israel had just four or five female competitors in the entire country.

“It was very hard to get to a high level when you don’t really have someone to compete against in Israel,” Zamir said. “Anat was working very hard; I respect her very much for what she did. And she has an amazing family supporting her.”

In fact, it was Anat’s father, Yochai, who lobbied the ISA to let her compete in the boys’ contests.

“In the beginning we said no,” Zamir recalled.

Eventually the association would relent. Anat joined the boys’ contests, then began to travel and compete outside the country against bigger pools of female athletes. At the same time, surfing’s popularity in Israel continued to grow, and more girls began to compete.

While Anat sometimes struggled to find the competitive resources in a system that wasn’t yet ready for her, her family filled in with support in every way. Not only did her parents supply her with equipment and occasional plane tickets but also with in-house training partners: her older brother, Ido, and her younger sister, Noa, who also competed until she was derailed by an injury. Having each other to surf with helped them up their games.

It was Noa who spearheaded Anat’s first visit to a much bigger stage in surfing. Now 18, when Noa was 12, she asked if, in lieu of a party for her bat mitzvah, the family could go to a surf contest abroad. Yochai and the sisters packed up and headed for their first Qualifying Series (QS) and junior-level contest in France – a massive step up from local competitions.

“It was such a treat,” Yochai said. “We did this competition and then we went to Pantin [Spain, which also hosts a QS contest]. The seed was planted. One event can make a difference for a person’s life in her journey.”

The trip was the family’s first to a higher-tier, international event, but far from their last. Anat continued to compete at home and abroad, and in 2019 she provisionally qualified as Israel’s entrant to the Olympics at the International Surfing Association’s World Surfing Games in El Salvador. A few weeks ago, the family was there again to cheer on Anat as she secured her spot in Tokyo.

In contrast to many of her Olympic peers, Anat’s formative years in the sport were largely a journey of one.

“It’s so hard to be so alone in this kind of a journey, to have to break so many barriers,” Yochai said. “You question yourself so many times. You are not in a community of surfers. To be a woman surfer with no competitions for you, and to be able to grow from that. To go to the army, and to go to school; this feeling that you always have to be in two places at the same time.”

Those who have watched Anat’s evolution in the water and out say that it’s not only her talent, work ethic and uniquely supportive family that have gotten her here.

“Anat has a very strong internal energy,” Rashkovan said. “She’s something else, she’s a different kind of person. She’s very strong-minded.” In other words, she has the kind of toughness required to forge her own way in a highly competitive, male-dominated sport.”

Anat’s road to the Olympics means more than just reaching the pinnacle of her sport. Yochai said.

“In a way, making the Olympics says yes, your work, your achievement, is visible. Yes, you are a woman. You are a surfer. You are an Israeli. You are Jewish. You’re a lot of things. But the Olympics, it’s confirmation.”

This article originally appeared on Alma.

Baseball Briefs

Baseball phenom Jacob Steinmetz becomes first Orthodox player drafted into MLB

By Rob Charry

(JTA) – The Arizona Diamondbacks drafted Long Island, New York native Jacob Steinmetz 77th overall in the third round of the Major League Baseball draft on Mon-day. He’s the first known observant Orthodox player to be picked the league’s draft.

MLB.com ranked the 17-year-old as the 121st best major league prospect, so he was picked far earlier than expected.

Steinmetz, a 6-foot-5, 220 pound pitcher, spent the past year at ELEV8 Baseball Academy in Florida, honing his pitching skills while attending The Hebrew Academy of the Five Towns and Rockaway in Long Island via Zoom. His fastball has reportedly reached as high as 97 miles per hour.

Steinmetz keeps kosher and observes Shabbat, but he also pitches on the Sabbath. To avoid using transportation on Shabbat, he has in the past booked hotels close enough to games that he can walk to them, the New York Post reported.

Starting pitchers in the big leagues only pitch every five days, so his schedule could theoretically be planned to skip Shabbat.

Steinmetz comes from an athletic family – his father Elliot played basketball at Yeshi-va University and is now the New York school’s basketball coach. He had coached the team to record success before the pandemic.

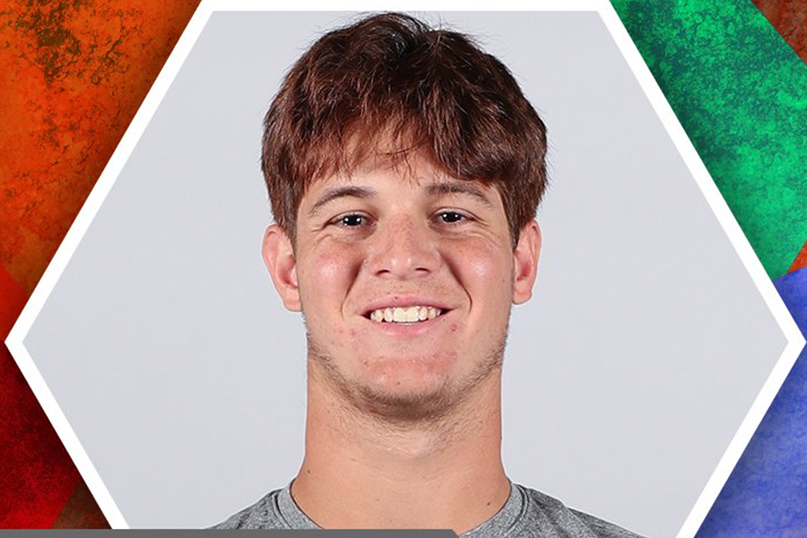

Elie Kligman is 2nd Orthodox baseball player drafted into MLB in 2 days

By Gabe Friedman

(JTA) – It has now become a doubly historic Major League Baseball draft.

The Washington Nationals selected Elie Kligman with their final and 20th round pick on Tuesday, making him the second observant Orthodox Jewish player ever drafted into the league – and the second in two days. The Arizona Diamondbacks picked 17-year-old Long Island, New York native Jacob Steinmetz 77th overall on Monday.

According to MLB.com, Kligman, 18, has moved towards becoming a catcher but has also played shortstop and thrown the ball 90 miles an hour as a pitcher. (The pitcher Steinmetz has reportedly touched as high as 97 miles per hour.) Kligman switch-hits as well, meaning he can bat righty or lefty, a skill that boosts his future value.

The Las Vegas native is also more observant than Steinmetz. While Steinmetz plays on the Jewish Sabbath – albeit in walking distance of his hotels on the road, so he does not have to use transportation – Kligman does not.

“That day of Shabbas is for God. I’m not going to change that,” he told The New York Times in March.

His father Marc is a lawyer and licensed baseball agent, and he represents his son. On Tuesday, Marc Kligman was traveling with Israel’s baseball team, currently on a pre-Olympics road trip full of exhibition games across the Northeast, when he heard the news. He shared it with the players on one of their buses.

The Times reported that Kligman’s recent switch to playing catcher could be in service of his professional goals. Even the best at the sport’s most physically demanding position are often given at least one day a week off – opening up the possibility that Kligman could line up his days off to be during Shabbat, from Friday night through Saturday evening.

Despite the excitement of being drafted, Kligman will likely look to first play at a Division I college program before a professional career, his father told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

“Here’s a kid who won’t put God second,” Marc Kligman told the Times. “But he believes that the two can coexist. He’s got six days of the week to do everything he can to be a baseball player, and if colleges and Major League Baseball aren’t inclined to make any changes, then we’ll take what we can get.”

Main Photo: Anat Lelior (Design by Grace Yagel/Getty Images)

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger