Theologian, author, and educator Dr. Richard Lowell Rubenstein died this past May in Bridgeport. The University of Bridgeport professor was known for his groundbreaking works on the meaning of Judaism, religious life, and contemporary civilization in the aftermath of the Holocaust and the rise of the state of Israel. His 1966 book, After Auschwitz: Radical Theology and Contemporary Judaism (1966;1992) was among the first to systematically probe the significance of Auschwitz for post-holocaust religious life and initiated debate which continues to this day. In 2016, on the 50th anniversary of its publication, Dr. Rubenstein discussed his landmark – and controversial – book After Auschwitz with Judith Shapiro. An excerpt from that interview is reprinted here.

JUDY SHAPIRO: After Auschwitz provoked considerable controversy when it was first published in 1966. When I asked you why, you gave me two reasons. The first reason was that you were asking the one question that major Jewish thinkers were avoiding. What question were Jewish thinkers avoiding, and why?

RICHARD RUBENSTEIN: They were avoiding the question of God’s special relationship to Israel. Belief in that relationship – in God’s Covenant with Israel – had sustained us for almost 2,000 years, in the face of expulsions, pogroms, and blood libels. The Covenant sustained us because it provided a rationale for our successes as a people, but also more pointedly, it provided a rationale for the catastrophes that befell us. The catastrophes were regarded as punishment for disobeying God’s commandments. Thus, the Prophet Amos (ca. 750 BCE), spoke of the Covenant: “You, only, have I chosen from among all the peoples of the earth; therefore I will visit upon you your sins.” (3:2)

The credibility of that rationale was severely challenged by the Holocaust. A pogrom could be seen as divine punishment; the Final Solution, whose objective was extermination, could not.

According to contemporary scholars, the centrality of the Covenant commenced with the reforms of King Josiah of Judah, the southern kingdom, (2 Kings 23) in the seventh century B.C.E. The Jews were still worshipping idols and Josiah used the Covenant with God to impress upon the Jews that they had to be quit of their pagan practices, which included child sacrifice and ritual prostitution, and return to God and his commandments. If not, God would surely punish them. On the other hand, if they obeyed God, they would be blessed. Those were the terms of the Covenant and the special historical role of the Jews as the Chosen People.

That is how both Jews and Christians came to understand the Covenant. The difficulty of maintaining belief in such a Covenant for Jews after Auschwitz struck me with full force when, as the guest of the Bundespresseamt, the Press and Information Office of the West German Government, I interviewed the German theologian and churchman, Heinrich Gruber on August 17, 1961, four days after the Berlin Wall went up, a very scary time. Gruber had opposed Hitler and spent three years in concentration camps for his attempts to help the Jews. He was no antisemite. After the War he became dean of St. Mary’s Church in Berlin.

What he said to me when we met was this: “It was God’s will to send Hitler to punish the Jews at Auschwitz.” What he was saying was no different from what Jewish theologians were thinking, even if they couldn’t say it outright. His words, after all, were in keeping with the traditional notion of the Covenantal relationship dating back to King Josiah. There was no way I could accept what he said.

JS: Does this mean that God’s Covenant with the Jews post-Holocaust no longer exists?

RR: It means that the Covenant with the Jews – the special status claimed for the Jews as the Chosen People, conditioned on their obeying the Holy Law or being punished for disobeying – was no longer credible. What worked for Josiah is not likely to work after Auschwitz.

Nevertheless, religion and religious ritual remain indispensable. This is especially true of lifecycle events such as the death of a family member with its rituals of leave-taking, the solemnization of a marital bond, or puberty rites, and in that sense the Covenant exists today as part of who we are; a social-psychological perception of what it means to be a Jew. That is why I go to religious services regularly. The Covenant as something that actually happened may no longer be credible, but the Jewish people must live, and there are times in our lives that remain sacred, that is, of decisive importance, to us, even if objectively we are not a Chosen People. We will not find that newly invented rituals can do for us what our traditional rituals can.

What matters now are our hallowed, ancient traditions, not because they are better than other men’s or because they are somehow more pleasing in God’s sight. We cherish them simply because they are ours, part of our family memory, and we would not with dignity or honor exchange them for any others. Every tradition has got to have rituals with which to deal with lifecycle events. We are no different.

JS: The second reason you gave for the book’s controversy was that you were making the case that religion played a larger role in the Holocaust than people wanted to admit.

RR: Yes, religion played a large role in the Holocaust and it starts with Paul of Tarsus and Augustine who wanted Jews to survive so that they could eventually come to recognize Jesus Christ as their Savior. Augustine said it best: “Jews must survive but not thrive.”

Hitler, however, was not interested in persecuting the Jews; he sought to exterminate them. He claimed that the Jew sought to destroy Christian civilization. What made his claim credible was that Jews had been among the leaders of the Russian Revolution and of Bolshevism, an intellectual movement that believed in an alternative, godless society. European Christians were already primed to view Jews as outsiders. It was not asking too much to have them now view the Jews as purveyors of godless communism seeking to destroy Christian civilization.

The future Pope Pious XII, who would be pope during World War II, witnessed the establishment of the Munich Soviet Republic in 1918 as the Papal Ambassador to Germany. The founder of this short-lived attempt to establish a socialist state in the Free State of Bavaria, was Kurt Eisner, a Jew. There were also Trotsky and the Red Army, etc.

JS: When the second edition of After Auschwitz was published in 1992 … chapters were eliminated, others were revised, and other new ones were added. At the time you explained that the first version contained a “spirit of opposition and revolt,” while the second contained a “spirit of synthesis and reconciliation.” I understand the “spirit of opposition and revolt” you felt in 1966. But can you explain the “spirit of synthesis and reconciliation” you were feeling in 1992.

RR: I’ll start with reconciliation. I am reconciled in the sense that I have more sympathy for those who opposed me and even attempted to deprive me of my vocation. I now realize how painful it was for them to hear what I was saying. And in that sense I am reconciled to the struggles I had as an outlier. The synthesis comes from my belief that we Jews are or should be all in this together. And in that regard I have to say that I feel that this congregation and this rabbi are part of my extended family. I have found my religious community. And for that I am grateful.

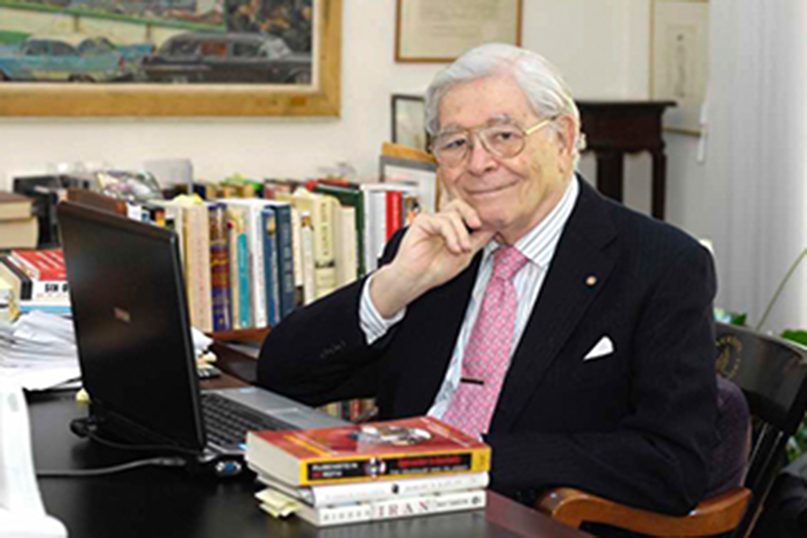

Main Photo: Dr. Richard L. Rubenstein

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger