By Bat-Ami Zucker

A review of The Rabbi of Buchenwald by Rafael Medoff

(Yeshiva University Press; distributed by ktav.com; 502 pages., $29.95.)

There is a remarkable scene, early in The Rabbi of Buchenwald, which sounds like something out of a movie – and perhaps should be. It takes place in May 1945, soon after the American Army liberated that notorious Nazi concentration camp. The Swiss government has just offered to admit 350 Buchenwald children under the age of 16. The problem is that not enough children survived that Nazi hell to take full advantage of the offer.

An intrepid United States Army chaplain, Rabbi Herschel Schacter, tries to pass off a number of young adults as young teens so they can board the train taking them to a new life. A suspicious Swiss Red Cross inspector, one Sister Kasser, disqualifies many of the would-be passengers for exceeding the age limit. Rabbi Schacter finds a printer in nearby Weimar to create a rubber stamp bearing the Red Cross emblem. The rabbi and two confederates break into Kasser’s office, help themselves to blank cards of the type she gave to qualified passengers, and spend the night forging the signatures needed to confirm that the holder is of the required age. The next morning, as Kasser stalks through the train in search of stowaways, older children in cars ahead of her elude discovery by jumping from the train and running back to the cars through which she has already passed. In this madcap fashion, many more than 350 Buchenwald children make it to Switzerland.

Some years ago, I wrote a book about the American Jewish social worker Cecilia Razovsky, who aided Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis, and who was there in 1945 to help organize the Buchenwald children’s train. Now I see that the determined and resourceful Razovsky had her counterpart – and then some – in the young U.S. Army chaplain whom she assisted in Buchenwald.

Rafael Medoff’s new study, The Rabbi of Buchenwald, is at once a biography of Schacter and a history of postwar American Jewry, viewed through the lens of the many leadership positions Schacter held and the ways he impacted the community. During the course of nearly half a century in Jewish public life, Schacter was the rabbi of a successful synagogue in the Bronx and a pioneer in early U.S. Orthodox outreach efforts, as well as chairman of national Jewish organizations such as the Religious Zionists of America, the American Conference on Soviet Jewry and, most important, the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations.

Schacter was the first Orthodox Jew to chair the Presidents Conference, which, Medoff shows, represented a kind of coming-of-age for Orthodox Judaism in America. The old stereotype of Orthodox Jews as insular and unsophisticated gave way, in the 1960s, to a generation of young rabbis such as Schacter – impeccably tailored, speaking unaccented English, and entirely capable of leading the entire Jewish community, not merely its religiously observant minority.

Deeply researched through archival documents and numerous interviews, Medoff’s well-written narrative explores Schacter’s involvement in a slew of Jewish public controversies. Some of those conflicts will seem familiar to contemporary readers, from disputes over Israel’s Jewish identity to clashes with U.S. government officials who were pressuring Israel to make one-sided territorial concessions. We read of a rain-drenched Schacter picketing the Polish Embassy in Washington (to protest that government’s scapegoating of Jews), a magnanimous Schacter inviting Jewish militant hecklers to join him on the podium, and a rather chutzpahdik Schacter entangled in a comic incident involving the president of the United States and a pair of cufflinks – to mention a few of the many episodes in this scholarly but very readable work.

The Rabbi of Buchenwald illustrates Medoff’s versatility as a historian. Founding director of The David Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies in Washington, much of his earlier, critically acclaimed scholarship focused on how President Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Jewish leaders responded to news of the Holocaust. This story, however, begins where his earlier chronicles left off, just as the Holocaust is ending. It focuses on an American Jew who did not merely read about Nazi atrocities or watch newsreel footage of the liberated camps, but actually chose to spend 10 nightmarish weeks in Buchenwald, assisting the survivors as they tried to rebuild their lives.

The Rabbi of Buchenwald is not hagiography. Medoff presents a full picture of Herschel Schacter, the leader and the man, and he was not flawless. Serious scholarship shows us history in its full scope, not just the most flattering or pleasant parts.

Most of all, what Medoff shows is that while Schacter left Buchenwald after two and a half months, Buchenwald never left Schacter. “What I saw in Buchenwald was seared into my heart and mind,” Schacter often said. He saw, first hand, the consequences of the Nazis’ depravity and the Jews’ vulnerability, and he devoted the rest of his life to ensuring that the Jewish people would have the military, political and spiritual fortitude to prevent it from ever happening again.

Bat-Ami Zucker is a professor of history at Bar-Ilan University.

Reprinted from the Washington Jewish Week by permission of the author. It has been lightly edited for space.

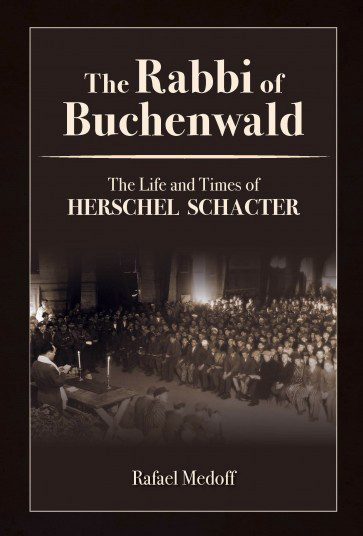

Main Photo: Rabbi Herschel Schacter speaking in 1971.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger