By Rafael Medoff

President Trump’s recent remark about Henry Ford’s “good bloodlines” has aroused curiosity and controversy. Trump actually is not the first president to subscribe to the discredited notion that there is such a thing as “good” blood and “bad” blood. But you have to go back nearly a century to find another American head of state who openly embraced such notions.

During his visit to a Ford Motor Company plant in Michigan on May 21, Mr. Trump was supposed to read from a prepared text, in which he would state simply, “The company founded by a man named Henry Ford teamed up with the company founded by Thomas Edison – that’s General Electric.”

But with Ford executive chairman William C. Ford Jr., the great-grandson of Henry Ford, standing nearby, Trump turned to him and ad-libbed: “The company founded by a man named Henry Ford–good bloodlines, good bloodlines, if you believe in that stuff. You got good blood. They teamed up with the company founded by Thomas Edison – that’s General Electric. It’s good stuff. That’s good stuff.”

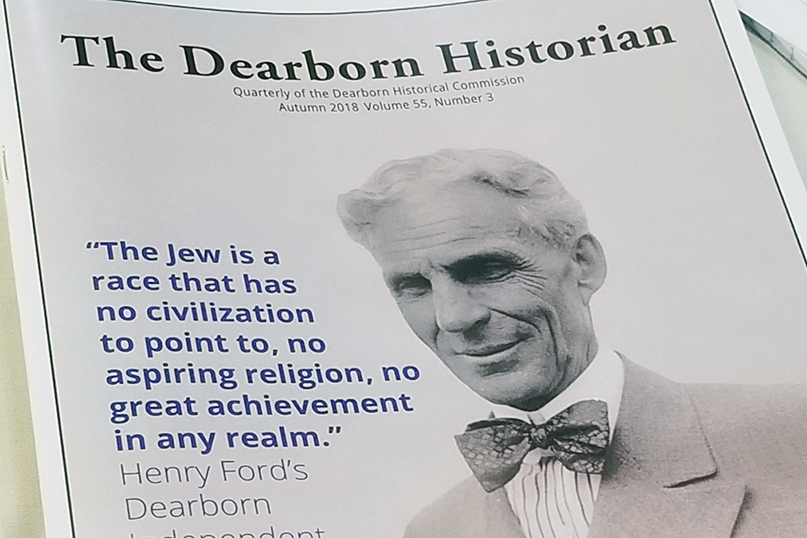

One wishes the president of the United States would have more than a passing familiarity with American history. Perhaps it is unrealistic to expect Mr. Trump to know that Henry Ford was America’s worst promulgator of antisemitism in the 1920s – for which Adolf Hitler praised him, by name, in the pages of Mein Kampf. Or that Ford accepted Nazi Germany’s highest award for foreigners, the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, in 1938. Still, Trump’s advisers and speechwriters have an obligation to keep him fully informed.

The more disturbing question, however, pertains to President Trump’s references to “good blood.” Granted, he inserted the caveat, “if you believe in that stuff.” But the very fact that he brought it up, unprovoked – and the fact that he has made similar remarks in the past – suggests that he, for one, does “believe in that stuff.”

In 2016, Mr. Trump told British business leaders that they have “good bloodlines” and “amazing DNA.” At a rally in Mississippi that year, he said, “I have great genes and all that stuff, which I’m a believer in.” In a 2014 documentary, he said, “I’m proud to have that German blood, there’s no question about it. Great stuff.”

Some of his statements regarding genes and blood concern his uncle, the late Dr. John Trump. As a presidential candidate in 2015, he asserted at one rally that he has “good genes, very good genes, okay, very smart” as supposedly proven by the fact that his uncle was a professor at MIT. Earlier this year, President Trump said he believes he has “a natural ability” in the field of medicine because his uncle “was a great super genius.”

The idea that a person’s abilities and behavior are determined chiefly by their “blood” or genes was widespread in the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It went hand in glove with the notion that whites from northern Europe were a superior race that was under siege by inferior races from Africa, Asia, and southern and eastern Europe.

Such attitudes extended even to the White House. Theodore Roosevelt wrote in 1897 – just a few years before he became president – that it was important to “keep for the white race the best portion of the new world’s surface.” He insisted it was the responsibility of “Anglo-Saxon women” to bear children “numerous enough so that the race shall increase and not decrease.”

Woodrow Wilson wrote a book in 1902 in which he warned that “men of the lowest class” from Italy and “of the meaner sort” from Hungary and Poland, were “men out of the ranks where there was neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence; and they came in the numbers which increased from year to year, as if the countries of the south of Europe were disburdening themselves of the more sordid and hapless elements of their population.”

There is “a fundamental, eternal, inescapable difference” between the races, President Warren Harding declared in a speech in 1921. “Racial amalgamation there cannot be.”

Vice president – and soon to be president – Calvin Coolidge wrote in Good Housekeeping magazine in 1921: “There are racial considerations too grave to be brushed aside for any sentimental reasons. Biological laws tell us that certain divergent people will not mix or blend. The Nordics propagate themselves successfully. With other races, the outcome shows deterioration on both sides.”

Based on that premise, the U.S. government adopted restrictive immigration laws, based on national origins, in the early 1920s. “We have closed the doors just in time to prevent our Nordic population being overrun by the lower races,” Senator David A. Reed, one of the authors of the restrictive legislation, asserted in a New York Times oped. “The racial composition of America at the present time thus is made permanent.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt shared these sentiments. In the 1920s, he wrote articles warning that “the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results.” He asserted that America should welcome European immigrants who possessed “blood of the right sort.” In 1939, as president, he privately boasted to a Senate ally that “we know there is no Jewish blood in our veins.”

FDR’s harsh policy of suppressing Jewish refugee immigration far below what the quota laws allowed, in the 1930s and 1940s, reflected his vision of a United States that was overwhelmingly white, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant. In his view, modest numbers of foreigners should be admitted only if they were, as he put it, “spread thin” around the country and thoroughly assimilated.

With the advent of modern science and more enlightened views concerning race and culture, century-old attitudes about one race being better than others generally have been discarded, except among a small fringe of extremists. All that talk about the value of “good bloodlines,” which did not disturb many people eighty or a hundred years ago, by now should be a thing of the past. The fact that the president of the United States is expressing such views in the year 2020 is a reminder that some bad ideas do not easily go out of style.

Dr. Medoff is founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and author of more than 20 books about Jewish history and the Holocaust.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger