By Jonathan S. Tobin

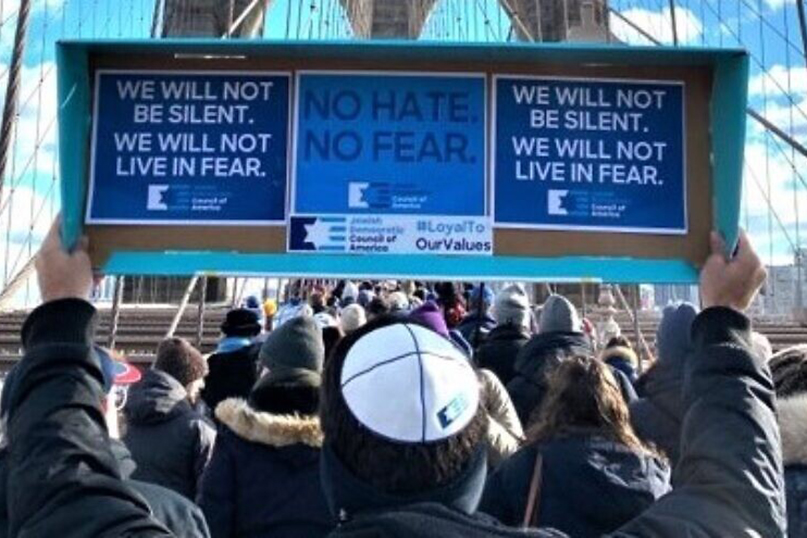

(JNS) The march over the Brooklyn Bridge and the ensuing rally against antisemitism on Jan. 5, attended by an estimated 25,000 people, was a necessary, if belated, response to a surge of attacks against Jews in the Greater New York area in the last year. That so many Jews were willing to openly express both their pride in being Jewish and their willingness to publicly stand up against hate sent an important message to the world, as well as inspiring Jews throughout the United States to express solidarity with the victims of the scourge of hatred that has come their way of late.

But in the aftermath of the rally, some unanswered questions still loom over the warm feelings that the march generated: What can we do about antisemitism among African-Americans, and how can we discuss it in a way that will confront the sources of hate without engaging in rhetoric that will be interpreted as racist and thus exacerbate the problem?

The difference between the crime spree against ultra-Orthodox Jews in New York, and what happened in Pittsburgh and Poway, Calif., is that the perpetrators of the latter crimes fit most of the Jewish community’s general idea of an antisemite. We’re used to thinking of far-right white-supremacist/neo-Nazis as Jew-haters we should despise and fear. However, those responsible for the attacks against Chassidim in Brooklyn, the shooting at a kosher supermarket in Jersey City and the stabbings at a rabbi’s house in Monsey were black.

So it was little surprise that not only was the organized Jewish community, which rightly regards the struggle for civil rights for African-Americans as linked to the battle against antisemitism, was slow to react to the attacks in New York. But now that the leading groups are trying to take this problem seriously, their resolve is being undermined by a sense within much of the Jewish community that speaking too loudly about antisemitism among blacks is tantamount to racism. The same arguments are being thrown about criticizing the efforts of those who are trying to change a new “bail reform” law that has resulted in the release of some of those guilty of attacking Jews.

Generalizing about blacks and antisemitism is a mistake.

The presence of African-American community leaders and politicians at the march was heartening. So, too, are the many testimonies that have come forward from individuals about acts of caring and kindness towards the ultra-Orthodox community that has been targeted for violence from many of their African-American neighbors. Those who would treat this as a conflict between two communities that are locked in an existential struggle are wrong.

Yet the history of black-Jewish relations, especially in New York City over the last half century, is complicated. While they might have once seemed like two minority communities that were natural allies in the struggle for civil rights, blacks and Jews also found themselves on the opposite sides of many issues in the 1960s and its aftermath. And the antisemitism of many leading black activists in the 1960s during conflicts over housing, the education system and other disputes was a distressing development.

The tensions between poor blacks and the ultra-Orthodox Jews who remained in Brooklyn neighborhoods that other Jews fled might have created misunderstandings on both sides. But the Crown Heights riots of 1991 that activists like Al Sharpton helped incite, in which a 29-year-old Orthodox Jewish student from Australia was murdered and many others injured, was part of this legacy. The fact remains that surveys over the last quarter century have consistently shown that African-Americans hold antisemitic views at a rate far higher than the rest of the population. Twenty years after Crown Heights, an Anti-Defamation League survey showed that 29 expressed “strongly antisemitic views.”

That problem has grown worse as black activists have embraced false intersectional theories that view Jews and Israel as on the other side of an intractable divide between oppressors and “people of color” even though the majority of Israelis can be described by the same phrase. There is nothing remotely in common between the struggle for civil rights in this country and the Palestinian war to destroy the only Jewish state on the planet.

Nor can the influence of hatemongers like Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, a group that has far more active followers and sympathizers than any of the white-supremacist groups, be denied.

Many in the Jewish community prefer to downplay these factors because they don’t fit into their preferred narrative about antisemitism—and of late, that President Donald Trump has something to do with it. Others, like the Reform movement of Judaism, thinks the problem is Jewish racism, as Rabbi Jonah Pesner stated when successfully urging the denomination to support reparations for the descendants of African-American slaves. Such sentiments meld with those who prefer to blame the victims of the violence and see attacks on Jews as a natural reaction to gentrification or economic exploitation of blacks.

These fallacious arguments are sometimes rooted in the prejudicial attitudes many secular and non-Orthodox Jews have about the ultra-Orthodox. Nor is it out of line or racist to ask more African-American leaders to be outspoken in denouncing antisemitism in their communities and encourage programs, such as those promoted by the ADL, which will help young blacks see through the lies told by the Jew-haters.

Yet as much as we must resist the impulse to avoid criticizing black antisemitism because of their long history of oppression, the opposite is also true. It is equally important for those calling attention to black antisemitism to realize that Jews and blacks are not competing for victim status. Nor is it helpful or accurate to assume that minority communities are invariably hostile, or that common ground can’t still be found. This discussion can be derailed by insensitive or needlessly inflammatory rhetoric, even if the motives of those speaking out on the issue are not racist. How we discuss the reality of black antisemitism is as important as our willingness to acknowledge it.

Jonathan S. Tobin is editor in chief of JNS—Jewish News Syndicate. He is also a contributing writer for National Review and a columnist for the New York Post, Haaretz and other publications.

Main Photo: Some 25,000 people converged on Manhattan’s Foley Square, crossed the Brooklyn Bridge and made their way to Cadman Plaza as part of a “No Hate. No Fear.” rally on Jan. 5, 2020. (Credit: Halie Soifer/Jewish Democratic Council of America)

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger