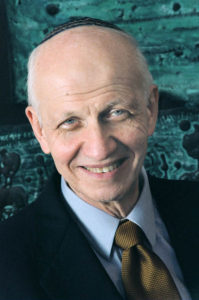

By Rabbi Irving Greenberg

Why does Yom HaShoah come out on the date of Yom HaShoah, that is, on 27 Nisan on the Hebrew calendar [which begins this year on the evening of May 1]?

The date of the mourners’ day for the destruction of the Temple was set on 9 Av, the traditional anniversary of the day in 70 C.E. when the Romans set the Beit HaMikdash (Holy Sanctuary) on fire. Passover is celebrated on 15 Nisan, the full moon of the spring month, the traditional anniversary of the Israelite Exodus from Egypt. But no one great catastrophe in the Holocaust occurred on 27 Nisan.

In actual fact, 27 Nisan represents no actual historical anniversary. The placement of Yom Hashoah is the outcome of pluralism in Jewish life and a profound philosophical and religious judgment. Understanding the timing is critical to the proper understanding of Yom HaShoah.

First, the pluralism. The initial pressure for a day to commemorate the Holocaust came from the survivors of the Holocaust in Israel, specifically from leaders of the ghetto fighters, partisans and the underground resistance to the Nazis.

After the Shoah, they came to Israel with strong connections to the Zionist leadership which shared their views. People like David Ben-Gurion originally came from those destroyed communities. They mourned the destruction and were committed to commemoration. However, the fighters were determined to remember and honor the uprisings, above all. They were somewhat embarrassed that the six million victims of the Shoah did not fight back.

Sad to say, the worldwide Jewish people – which had failed to do enough to protest the ongoing Holocaust, which had failed to inform and help European Jewry, which had failed to press the Allies to take adequate measures – initially reacted by blaming the victims for not saving themselves. This temporary aberration of judgment – which overlooked the victims’ heroic stand for dignity and preserving the image of God of every Jew in the Shoah – eventually passed as deeper understanding set in.

To the ghetto fighters, the appropriate day of commemoration was the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising – April 19, 1943, 15 Nisan, 5703. They would remember all the victims of the Holocaust but they wanted to hold up the fighters as the ideal symbols of Jewry in extremis.

Of course, 15 Nisan is the first day of the Pesach holiday, the anniversary of the Exodus, the core redemption event of Jewish history. The representatives of Orthodox Jewry strongly objected to using this date. The heart of Judaism is its affirmation that the world will be perfected, that good will defeat evil, that freedom, dignity and justice are the ultimate birthright of everyone. To override this holiday of liberation and crush the day beneath the weight of woe and death of the Shoah would constitute surrender of Judaism’s message. It would turn the religion that chooses life into a commemoration of the triumph of death. In the political give and take, the date of Yom HaShoah was pushed off eleven days.

With hindsight, we can say that these objections included another deep truth. To honor and privilege the ghetto fighters in this way would have constituted a degradation of the vast majority of victims who were caught by surprise, overwhelmed by force, betrayed by circumstances. Their only possible heroism was to maintain their life and relationships and dignity as best they could in the face of catastrophe.

Choosing 27 Nisan makes a highly symbolic statement. Traditionally, days of mourning were excluded from the month of Nisan because it is filled with rejoicing and the afterglow of the Exodus. By permitting Yom HaShoah to be scheduled in this 30-day period, the Orthodox conceded that the Exodus message is wounded by the assault of the Shoah. But the proponents conceded that the Exodus remains the primary Jewish affirmation. Thus, the Jewish consensus spoke through pluralism.

The decisive vote was cast by the Zionist leadership, religious and secular alike. Yom HaShoah would occur eight days before Yom Ha’atzmaut, Israel Independence Day. This day celebrates the response of world Jewry to the total assault of death on life, the Shoah. Jewry renewed its life, took up power, and began the greatest rebirth and renaissance of its history.

Thus, Jews affirmed that without denying the fierce, incredible power of evil and death we, nevertheless, give the final word to life and redemption. The two days are forever twinned in opposition – as challenge and response, as victory of death and triumph of life, as death and resurrection.

One of the most effective traditions of Holocaust memory is the March of the Living. Thousands of young Jews from all over the world march together through Auschwitz and other places fraught with Holocaust tragedy on Yom HaShoah. But they go on to Jerusalem where they celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut together with the vibrant Jewish people in Israel.

This understanding must guide our commemoration of Yom HaShoah. We must not succumb to the tendentious claim that in America, the Jewish community has substituted the Holocaust for the positive message of the Torah. It is false that the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum or university chairs in Holocaust studies come at the expense of all the other forms of Jewish education.

Encounter with the Holocaust is like the Akedah (Binding of Isaac); tradition defines it as a nisayon (a test). In responding we are in danger of losing our soul, but in responding correctly we are elevated. In confronting the total death in the Holocaust, the Jewish people risked nihilism and despair but rallied to increase its commitment to life.

Now we know that in affirming life, we must be prepared to brave the worst that death can inflict on us. Now Jews know the tragic cost of our covenant of redemption. Wiser, more realistic, more determined than ever, we retell the whole Jewish story – of which the Holocaust is an inseparable, searing part – of the journey from slavery to freedom, from death to life.

This article was first published by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on April 7, 1996.

Rabbi Irving “Yitz” Greenberg was, at the time this article was written, founding president of CLAL – The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a position he held for 23 years. An influential theologian, activist and prolific author, he is widely regarded as a seminal thinker on the Holocaust as a turning point in Jewish and Western culture and on the State of Israel as the Jewish assumption of power hand the beginning of a new era in Jewish history. Among his many posts, he served as chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council from 2000–2002. He is currently writing a comprehensive theology of Judaism as the religion of tikkun olam, seeking to perfect the world.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger