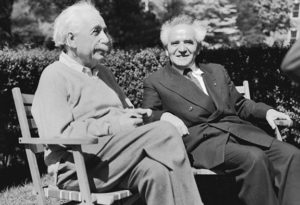

On the 140th birthday of Albert Einstein, Hebrew University reveals the content of its newly acquired archive of the brilliant physicist’s original manuscripts. (Embassy of Israel in Washington, D.C. via JNS) The one generally known story about Albert Einstein and Israel is true. The 20th century’s greatest scientific genius refused David Ben-Gurion’s offer to become its second president.

But this fact yields a false sense of Einstein’s relationship with Zionism. Einstein, who was born in 1879 and died in 1955, was a Zionist from 1919 onwards, when he was converted to the cause by Chaim Weizmann’s lieutenant, Kurt Blumenfeld.

Thus, in 1921, Einstein accompanied Weizmann on a fundraising tour of the United States for the planned Hebrew University. Attracting front-page headlines and enthusiastic crowds, it raised $700,000 – a remarkable sum in those days.

Two years later, in February 1923, Einstein visited British Mandate Palestine. During this trip, he gave the first scientific lecture at Hebrew University and joined Weizmann on its board of governors. Einstein continued to raise money for the university into the 1950s.

On that visit, he also planted a tree in front of the Technion, an institution he would later support, including serving as chairman of the Technion Society.

In the 1930s, Einstein took on an honorary post as chairman of the United Jewish Appeal. This involved more than lending his name. Einstein gave radio addresses about the dangers Jews faced in Europe and he denounced the limitations against Jewish emigration into Palestine.

Einstein’s decision to turn down Israel’s presidency was certainly not motivated by disregard or indifference, but rather by respect.

As he put it, “I am deeply moved by the offer from our State of Israel, and at once saddened and ashamed that I cannot accept it. … I lack both the natural aptitude and the experience to deal properly with people and to exercise official functions. … I am the more distressed over these circumstances because my relationship to the Jewish people has become my strongest human bond, ever since I became fully aware of our precarious situation among the nations of the world.”

In the last days of his life, Einstein was working doggedly on a speech in support of Israel. Although he died before he was scheduled to deliver it, the address survives. In it, he said Israel’s creation was “an event which actively engages the conscience of this generation. It is, therefore, a bitter paradox to find that a state which was destined to be a shelter for a martyred people is itself threatened by grave dangers to its own security. The universal conscience cannot be indifferent to such peril.”

Einstein bequeathed his personal archives and all literary rights to his works to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Recently, Hebrew University’s Albert Einstein Archives received an additional gift of new manuscripts – both personal and professional in nature – which were purchased from a private collector in Chapel Hill, North Carolina and donated by the Crown-Goodman Family Foundation in Chicago. The archives contain more than 80,000 items.

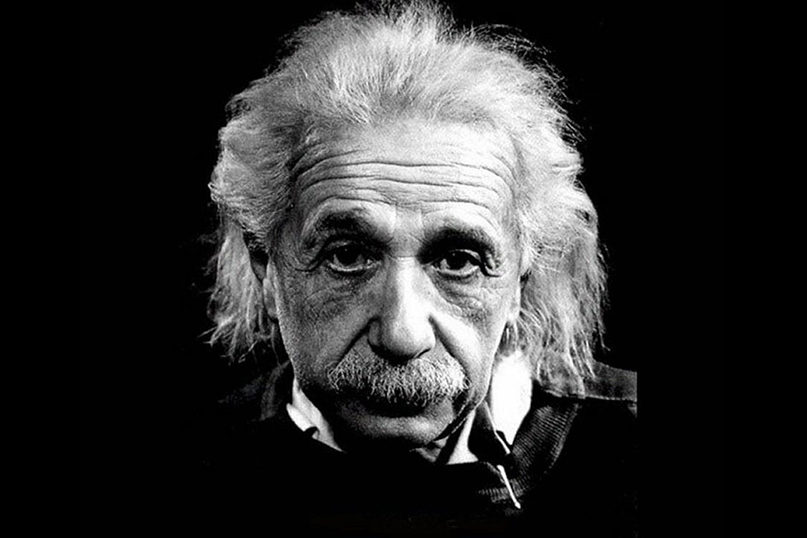

Manuscripts offer insights into Einstein’s mind

One thing is for sure. While the writing on the pages lying on the table under a clear protective glass appeared as nonsensical gibberish or useless, mind-bending mathematical equations, they were anything but. These were some of Albert Einstein’s original manuscripts – 110 pages in all – recently donated to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem by the Crown-Goodman Family Foundation, purchased from Gary Berger, a private collector in North Carolina.

The pages, donated just before Einstein would have turned 140 (he was born on March 14, also commonly known as Pi Day, when mathematics is celebrated), are just further testament to Einstein’s intellectual legacy.

His contributions to science are world-renowned and far-reaching. However, not many people make the connection between the Jewish physicist and the State of Israel, and how his brilliant theories years ago contributed to the science behind Israel’s alleged second-strike nuclear capabilities, as well as SpaceIL’s lunar lander “Beresheet,” currently hurtling at 6.5 miles per second through space towards an eventual and hopefully successful moon landing.

Karen Cortell Reisman’s grandparents Lina and Julius Kocherthaler with Einstein. (Lina is to the right of Einstein, in a white kerchief, and Julius, in the cap, is beside her.)Credit: Ardon Bar-Hama/Einstein Archives at Hebrew University.

Einstein was one of the founders of Hebrew University in Jerusalem. To him, the university represented a combined commitment to a Jewish identity, the pursuit of truth and respect for all human beings. For these reasons, Einstein bequeathed his personal and scientific writings to the university, and the Albert Einstein Archives were born.

As the Archives’ academic director Professor Hanoch Gutfreund shared, “We at the Hebrew University are proud to serve as the eternal home for Albert Einstein’s intellectual legacy, as was his wish.”

Karen Cortell Reisman, the granddaughter of Einstein’s cousin, Lina Kocherthaler, flew in from Texas to attend the celebration. She shared personal experiences of growing up and being related to Einstein.

“Whenever someone came to visit our home, we always showed them our ‘Einstein Wall,’ which was full of photos and letters from my grandmother’s famous cousin,” she recalled.

Kocherthaler and Einstein often traveled together and remained in close contact throughout their lives, sharing decades’ worth of correspondence.

“Later, when I got married, instead of a Tiffany bowl or crystal vase, I asked my family for a gift that would be much more meaningful to me: a July 1949 letter that Einstein, along with my father and mother, wrote to Lina,” said Cortell Reisman.

She offered a glimpse of the man behind the theories and explained that she wanted to show Einstein as a man with humility, grace and a sense of humor. She shared that he once wrote to a relative who was moving homes, quipping that she was moving her “center of gravity.”

‘An important addition to our collection’

Einstein’s 1930 appendix on Unified Theory. Credit: Ardon Bar-Hama/Einstein Archives at Hebrew University.

Dr. Roni Grosz, curator of the Einstein archives, said this is the largest collection of Einstein-related documents in the world – with more than 82,000 items to date – and will remain the foremost collection.

“On this occasion,” he said, “I want to take the opportunity to explain what it means for an archives to acquire 110 documents of this caliber. This is a rare find. While the content was known … these papers are a generous donation to the archives. It adds prestige to our institution.”

Grosz explained that the originals “are an important addition to our collection” though he emphasized that it would take time for his department to understand them fully, as “we do not know yet which pages belong together.”

The new collection contains a handwritten, unpublished appendix to a scientific article on the Unified Theory that Einstein submitted to the Prussian Academy of Science in 1930. The article was one of many in Einstein’s attempts to unify the forces of nature into one single theory and he devoted the last 30 years of his life to this effort, which physicists are still grappling with today. This appendix, Page 3, has never before been seen or studied, and was thought lost until now.

There is also a letter from Einstein to his son Hans Albert, who was living in Switzerland at the time. Einstein expresses concern about the deteriorating situation in Europe and the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany: “I read with some apprehension that there is quite a movement in Switzerland, instigated by the German bandits. But I believe that even in Germany things are slowly starting to change. Let’s just hope we won’t have a Europe war first … the rest of Europe is now starting to finally take the thing seriously, especially the British. If they would have come down hard a year and a half ago, it would have been better and easier.”

Four letters from Einstein to his life-long friend and fellow scientist, Michele Besso, are also included. Three of the 1916 letters refer to Einstein’s monumental work, based on a “glorious idea” about the absorption and emission of light by atoms. (This idea later became the basis for laser technology.) In the fourth letter, Einstein confesses that after 50 years of thinking about it, he still does not understand the quantum nature of light.

The letters to Besso also contain Einstein’s witty and personal remarks about family matters and Jewish identity. In one, he teases Besso for having converted to Christianity: “You will certainly not go to hell, even if you had yourself baptized.” Though Einstein is impressed that Besso is learning Hebrew and shared, “As a goy, you are not obliged to learn the language of our fathers, whilst I as a ‘Jewish saint’ must feel ashamed at the fact that I know next to nothing of it. But I prefer to feel ashamed than to learn it.”

Gutfreund was visibly excited when he said, “This is a birthday present for Einstein. … The importance of having originals is that it has significant research value.”

Parts of this report were written by Israel Kasnett.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger