In Holland, one of the world’s most expensive Chanukah menorahs hides in plain sight

By Cnaan Liphshiz

The Amsterdam Jewish Historical Museum’s Nieuwenhuys menorah. (Courtesy of the the Amsterdam Jewish Historical Museum)

AMSTERDAM (JTA) – Nothing about the appearance of object MB02280 at this city’s Jewish Historical Museum suggests it is the capital’s priciest Chanukah menorah, worth more than the average local price of a duplex home.

Shaped like the body of a violin, it is only 16 inches tall. Its base cradles eight detachable oil cups intended to function as candles on Chanukah, when Jews light candles to commemorate a 167 BCE revolt against the Greeks. They are set against the menorah’s smooth, reflective surface, whose edges boast elaborate rococo reliefs.

But for all its charms, the Nieuwenhuys menorah – its creator was the non-Jewish silversmith Harmanus Nieuwenhuys – doesn’t stand out from the other menorahs on display next to it at the museum. Far from the oldest one there, the menorah certainly doesn’t look like it’s worth its estimated price of $450,000.

The Nieuwenhuys menorah can hide in plain sight because its worth owes “more to its story than to its physical characteristics,” said Irene Faber, the museum’s collections curator.

Made in 1751 for an unidentified Jewish patron, the Nieuwenhuys menorah’s story encapsulates the checkered history of Dutch Jewry. And it is tied to the country’s royal family, as well as a Jewish war hero who gave his life for his country and his name to one of its most cherished tourist attractions.

The price tag of the Nieuwenhuys menorah, which does not have an official name, is roughly known because a very similar menorah made by the same silversmith fetched an unprecedented $441,000 at a 2016 auction. A collector who remained anonymous clinched it at the end of an unexpected bidding war that made international news. It was initially expected to fetch no more than $15,000.

Another reason for the more vigorous bidding: The menorah came from the collection of the Maduros, a well-known Portuguese Jewish family that produced one of Holland’s most celebrated war heroes. The Nazis murdered George Maduro at the Dachau concentration camp after they caught him smuggling downed British pilots back home. In 1952, his parents built in his memory one of Holland’s must-see tourist attractions: the Madurodam, a miniature city.

“I imagine the connection to the Maduro family drove up the price,” said Nathan Bouscher, the director of the Corinphila Auctions house south of Amsterdam, which has handled items connected with famous Dutch Jews.

Besides the menorah on display at the Jewish Historical Museum, the Netherlands has another very expensive one in the Rintel Menorah: A 4-footer that the Jewish Historical Museum bought last year for a whopping $563,000. Far more ostentatious than the modest-looking Nieuwenhuys menorah, the Rintel, from 1753, is made of pure silver and weighs several kilograms. It is currently on loan to the Kroller-Muller Museum 50 miles east of Amsterdam.

In countless wartime broadcasts, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands rallied the Dutch but mentioned Jews only three times. (National Archive of the Netherlands)

The Jewish Historical Museum has no intention of selling the Nieuwenhuys, Faber said, although it could attract even more spectacular bids owing to its provenance: It was bought by the late queen of the Netherlands, Wilhelmina, as a gift for her mother and given to the museum by her great-grandson, King Willem-Alexander.

“We don’t know who commissioned the work, but from the reputation of the artist and the amount of labor it took, it was probably a wealthy Jewish family, perhaps of Sephardic descent,” Faber told JTA a few weeks ago at the museum.

At the center of the object is a round network of arabesque-like decorations “that probably contains the owner’s initials in a monogram,” Faber said, “but we haven’t been able to decipher it. It’s a riddle.”

The monogram was one of several techniques that Nieuwenhuys and other Christian silversmiths in the Netherlands had developed for their rich Jewish clients.

Before the 19th century, no Jews were allowed to smith silver in the Netherlands because they were excluded from the Dutch silversmiths guilds, which were abolished in the 1800s.

“This exclusion was beneficial [to the guild] because it kept out competition, but it meant that Christian smiths needed to become experts at making Jewish religious artifacts like this menorah,” Faber said.

Works like the menorah on display at the museum illustrate how some Jewish customers clearly were art lovers with sophisticated tastes.

Whereas the Maduro menorah was symmetrical with Baroque highlights, the Nieuwenhuys is asymmetrical with rococo characteristics that were “pretty avant-garde for its time,” Faber said. The smooth surfaces are “another bold choice, showing finesse,” she added.

Whoever owned the menorah no longer possessed it by 1907, when Queen Wilhelmina bought it for an unknown price at an auction to give it as a gift to her mother, Princess Emma.

This purchase may appear inconsequential to a contemporary observer, but its significance becomes evident when examined against the backdrop of institutionalized antisemitism among other European royal houses and governments.

The German Emperor Wilhelm II, a contemporary of Wilhelmina, was a passionate antisemite who famously said in 1925 that “Jews and mosquitoes are a nuisance that humankind must get rid of some way or another,” adding, “I believe the best way is Gas.”

Belgium’s King Leopold III was more politically correct, stating magnanimously in 1942 that he has “no personal animosity” toward Jews, but declaring them nonetheless “a danger” to his country. He raised no objections when the Germans and their collaborators began deporting Belgian Jews to their deaths.

But in the Netherlands, where thousands of Jews found haven after fleeing the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisition of the 16th century, royals not only refrained from such statements but were genuinely “interested in other faiths, including the Jewish one,” Faber said.

Wilhelmina’s gifting of a menorah to her mother “isn’t strange for her,” Faber said. “I imagine she found it fun, something to talk about with her mother, to see together how it works.” After all, “Jews have always been under the protection of the Royal House.”

Except, that is, during the years 1940-45, when Queen Wilhelmina and the Royal House fled to the United Kingdom. Wilhelmina mentioned the suffering of her Jewish subjects only three times in her radio speeches to the Dutch people during five years of exile.

Whereas before the war “Jews always sought the Royal House,” during and after “it appeared Wilhelmina didn’t think too much about the Jews,” Faber said. This was “a stain” on relations between Dutch Jews and the Royal House, which underwent a “rupture.”

But this was gradually healed in the postwar years.

The fact that King Willem-Alexander, Wilhelmina’s great-grandson, in 2012 gave the Nieuwenhuys menorah on an open-ended loan to the Jewish museum on its 90th anniversary “symbolizes the healing of the rupture,” Faber said.

Israel and US postal services issue joint Chanukah stamp

JERUSALEM (JTA) – Israel Post and the U.S. Postal Service have issued a joint stamp for Chanukah.

The stamp also is meant to celebrate 70 years since the establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and the United States, Israel Post said in a statement.

The new stamp design was launched simultaneously in the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, the oldest synagogue in the United States, and at the American Center in Jerusalem.

“Today’s joint stamp issue is a symbol of the shared values and the cultural affinity between the United States and Israel,” U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman said at the Jerusalem ceremony.

Postal Service Judicial Officer Gary Shapiro said in Rhode Island: “Starting today, this work of art celebrating the Jewish Festival of Lights will travel on millions of letters and packages throughout America and around the world.”

The stamp art features a Chanukah menorah created using the technique of papercutting, a Jewish folk art, by artist Tamar Fishman. Behind the menorah is a shape that resembles an ancient oil jug representing the miracle of the oil that burned in the candelabra in the Holy Temple in Jerusalem after its sacking and recapture for the eight days necessary to resupply. Additional design elements include dreidels and a pomegranate plant with fruit and flowers.

The stamp is being issued in the United States as a Forever stamp, which will always be equal in value to the current first class mail one-ounce price. It will sell in Israel for 8.30 shekels, the cost of a regular first-class stamp.

The first joint U.S.-Israel Chanukah postal stamp was issued in 1996.

You can purchase yours now in The Postal Store®! #HanukkahStamp.

How a Chanukah song made its way into the Hebrew translation of Harry Potter

By Josefin Dolsten

(JTA) – If you read the Harry Potter series in Hebrew you may have noticed a curious Jewish fact: Though Sirius Black isn’t Jewish, the character sings a Chanukah song in one scene.

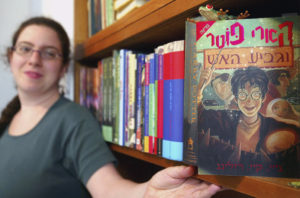

Gili Bar-Hillel with her Hebrew-language version of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, one of the four Harry Potter books she translated, in her Tel Aviv office, June 23, 2003. (David Silverman/Getty Images)

In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Hebrew translator Gili Bar Hillel reveals some behind-the-scenes tidbits about her Harry Potter translation process. In the original English version, Black parodies a Christmas song, “God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen,” but Bar Hillel felt that wouldn’t resonate with Israeli readers.

Instead, she referenced a well-known Chanukah song, “Mi Yimallel (Gvurot Yisrael)” so that Jewish readers would be able to relate.

“There were fans who ridiculed this and said that I was trying to convert Harry to Judaism, but really the point was just to convey the cheer and festivity of making up words to a holiday song,” she said. “I don’t think any of the characters come off as obviously Christian, other than in a vague sort of cultural way, so I didn’t feel it was a huge deal if I substituted one seasonal holiday for another!”

That wasn’t Bar Hillel’s only translation dilemma. She struggled with finding the right phrase for “Pensieve,” a container used to store memories. After weeks of thinking, she came up with the term “Hagigit.”

The phrase is “a portmanteau of ‘hagig’ – a fleeting idea – and ‘gigit’ – a washtub,” Bar Hillel said.

It doesn’t seem like author J.K. Rowling would mind the liberties Bar Hillel took. The British author has recently become a vocal critic of antisemitism, using Twitter to call out people peddling anti-Jewish arguments. Her latest book even includes a villain whose obsessive hatred of Zionism turns into antisemitism.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger