The Amichai Windows, opens a window onto love, war, and being Jewish in the 20th century.

By Judie Jacobson

The Amichai Windows – an 18-copy limited edition artist book of the poems of the renowned Israeli artist Yehuda Amichai – is an homage to one of the greatest Hebrew-language poets since King David. Amichai, who was born in Germany in 1924 and died in Israel in 2000, was nominated for the Nobel Prize and won numerous awards in Israel and abroad for his poems.

Created over the course of 10 years by book artist and poet Rick Black, the exquisite artist book is a bilingual collection of Amichai work that sheds light on love, war, and being Jewish today.

Andi Arnovitz, an American Israeli printmaker, book artist and multi-media artist, termed The Amichai Windows “a visual and tactile feast – not only does one become immersed in the words and images but one must reveal and discover the poems, too.”

Recently, the Yale University Library bought the first copy and will host a program, “Windows in the Poetry of Yehuda Amichai,” at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library on Tuesday, Oct. 30, 5 – 7 p.m. The evening will include a talk by Rick Black and a roundtable discussion and reception with several Yale University professors including Shiri Goren, Hebrew program director, Barbara Harshav, translator of Amichai’s poetry, and Katie Trumpener, professor of comparative literature and English. A copy of The Amichai Windows will be on display during the event.

“I want people to absorb the texture of the papers in their fingertips and the meaning of the words in their hearts,” said Black, a former New York Times reporter in Jerusalem who has run his own poetry press for the past 12 years.

Black lived in Jerusalem for six years, initially studying Hebrew literature on a scholarship at The Hebrew University. Subsequently, he got a job at the Associated Press, where he wrote and translated articles from the Hebrew newspapers plus the hourly news broadcasts. He then moved over to The New York Times, where he wrote cultural, business and travel pieces while also providing translations of the Hebrew media. Upon returning to the States, Black got a job as the press liaison at the Israeli consulate in Philadelphia. He ghost-wrote op-ed pieces for the consul general, coordinated media coverage of events and spoke to the Jewish community about the conflict in the Middle East – which is when he met Hana and Yehuda Amichai.

In 2005, Black founded a small poetry press called Turtle Light Press. Two years after that, Black suggested a limited edition artist book of Yehuda Amichai’s work to Amichai’s widow, Hana – and the result has been the production of The Amichai Windows.

JEWISH LEDGER (JL): Can you explain what an artist book is?

RICK BLACK (RB): A traditional book always has three aspects: a binding, covers and sequential pages. But an artist book does not have to have all of those things. It can have one or the other; it doesn’t even have to have words.

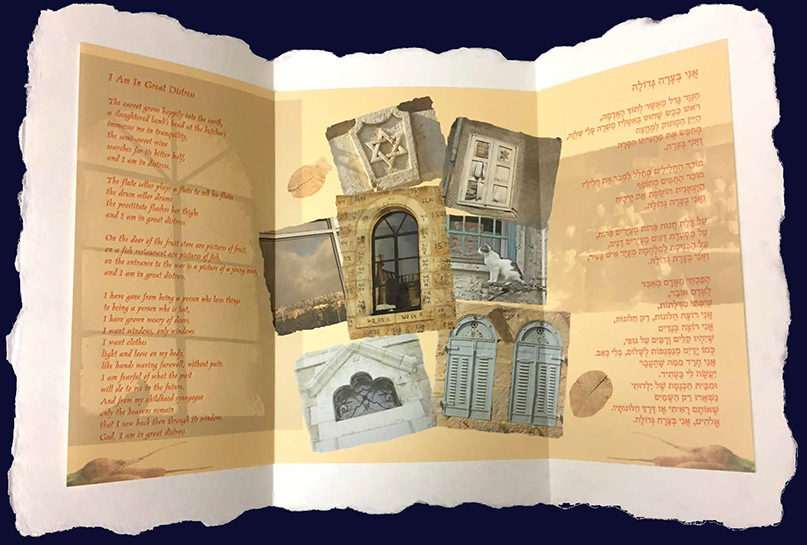

Book artists are constantly exploring and testing the boundaries of what a book is and can be. I like to merge the form and content of a book together. So, for instance, in The Amichai Windows, the container or box functions as a simulacrum of a window that needs to be opened – and then one comes to a curtain that one needs to lift up.

I am always playing with the idea of windows, of what is seen and not seen from a window. It’s similar to what we see and don’t see in a poem – they’re really metaphors for each other.

JL: Why did you print only 18 books?

RB: I only printed 18 books for a number of reasons. In Hebrew, the alphabetical letters have numerical equivalents. So, “aleph” equals one, etc. The word, “chai,” which means “life” or “alive,” has a numerical equivalent of 18. So, I wanted to reflect that in the number of the edition; but “chai” is also the last part of the poet’s name, Amichai. So, it’s also a tribute to him.

Moreover, Amichai was kind of a playful personality and I wanted to reflect that in the book. So, I blind embossed – that means that I ran the press without ink to make a colorless impression in the paper – I blind embossed the word “chai,” on each of the 18 poems, as if he were signing off on each triptych sheet, but it’s hard to see and you have to search for it.

Lastly, it has taken me 10 years already to make the book so who knows how long it would have taken to make even more copies! I am hoping to do an extended exhibition at a museum or library or find another way to share it with more people.

JL: What is the significance of the “windows” in the title The Amichai Windows?

RB: Hmnn… this could be a long answer. In brief, why windows? It’s a metaphor with its own symbolism. A poet’s window on the world; a view onto modern-day Israel and Jewish history as well as a look within at what it means to be a Jew today and our own personal experiences.

Here are the opening graphs of my intro to the book in the guide that accompanies it:

We often pause to gaze out a window. It allows us to center ourselves, to recover our balance, to reconnect with our surroundings. Sometimes we simply need to daydream, to let our minds wander aimlessly. Life passes in front of us – a constantly changing tapestry. Through a transparent pane of glass made of liquefied sand and other compounds, we can escape, if only momentarily, from a world defined by the walls around us.

The view out the window, though, is not always reassuring. Windows can get broken; danger can be seen approaching, too. We are both secure and vulnerable by a window; we can both see and be seen. What did Yehuda Amichai, one of the greatest Hebrew writers of our generation, see from his window? A soldier departing for war, a candle lit forever in memory of loved ones, a ship arriving at a sheltered port?

The Amichai Windows is an odyssey, a visual midrash, through Jewish history as filtered through the prism of 18 Amichai poems. The book is a cinematic collage of images that highlight the national and personal aspects of Amichai’s life. These photo montages span millennia in terms of geographic and temporal references, including birds and flight, exile, dislocated clock hands, Jewish ritual objects and, of course, curtains and windows.

JL: What drew you to Yehuda Amichai?

RB: In short, in a lot of ways Amichai was like a father figure to me, encouraging me to live again, to love again and to write poetry following a difficult part of my life as a war reporter in Israel.

What do I love about Amichai? Here’s a quote from him that I found in his papers at the Beinecke: “I am very happy that the poems which have helped me to heal myself also help others. I strongly believe that art has to heal and comfort and not just present the cruel reality of our modern life in Israel and the world over.”

Here’s another: “A poem is like a lullaby that you sing in order to calm yourself,” Amichai said in “Between the Pen and the Paper,” a 1965 Ha’aretz interview. “There are poems that if I hadn’t written them, I would have been completely lost.”

JL: You say that Amichai writes primarily about “love amid war” and about what it meant to be a Jew in the 20th century. And what did he have to say on those topics?

RB: Well, you really have to read the poems to answer that question; by the way, all of the translations in the book are my own. Here’s a few lines that I love from two poems, “I’m in Great Distress”:

“I want windows, only windows.

I want clothes light and loose on my body

like hands waving farewell, without pain.”

And the first stanza of a long poem, “My Son Was Drafted.”

“My son was drafted by the army. We brought him to the station with all the other youths.

Now his face, too, is added to the faces departing from me

in the passing bus and train windows of my life,

faces in pouring rain or blinded by sunlight. Now his face, too,

in a corner of the window, like postage stamps on letters.”

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger