Anne Frank’s stepsister brings her uplifting story of hope and survival to Hartford

By Judie Jacobson

HARTFORD – In Feburary of 1940, Eva Geiringer was nine years old and living a good life in her native Vienna when the rising tide of antisemitism forced her family to uproot their lives and resettle in Amsterdam. It was there Eva’s family met the family of Otto Frank, who had relocated to the city after fleeing their home in Germany. Eva became friends with one of the Franks’ two daughters – Anne.

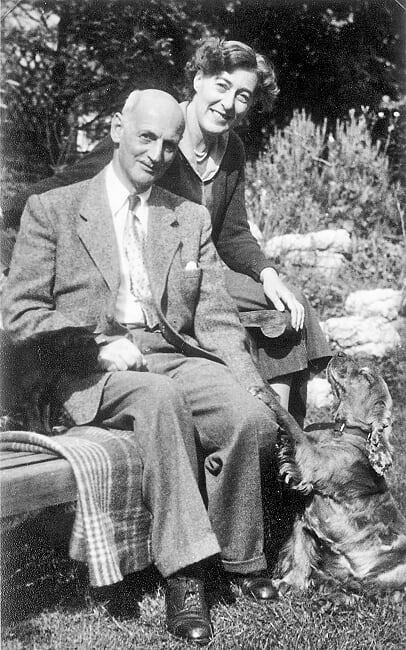

As the Holocaust intensified, both families were forced into hiding…only to be discovered and imprisoned in concentration camp. Only Eva and her mother, whom she called “Mutti,” survived, as did Otto Frank. Eva’s father and brother were killed, as was Otto Frank’s wife and two daughters. Otto Frank and Eva and Mutti (whose real name was Fritzi) were reunited. Eventually, Otto and Fritzi married.

Today, Eva Geiringer Schloss who lives in Europe with her husband Zvi Schloss, is a peace activist, international speaker, teacher and humanitarian.

Schloss will tell her compelling story on Sunday evening, Oct. 28 at the Klein Memorial Auditorium in Bridgeport. Her talk is sponsored by Chabad of Fairfield.

She will also speak at a special event hosted by Chabad of Greater Hartford on Monday evening, Oct. 29 at The Bushnell Performing Arts Center in Hartford, following Chabad’s Annual Gala.

“While Eva’s story recalls a time of great darkness, it also reminds us of the power of hope and how we can each make a positive difference,” says Rabbi Yosef Wolvovksy of Chabad Jewish Center in Glastonbury, pointing out that Schloss’ talk coincides with the 80th anniversary of the infamous Kristallnacht – the Night of Broken Glass – that took place on Nov. 9, 1938.

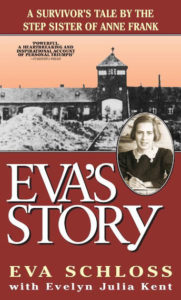

The author of Eva’s Story: A Survivor’s Tale, Schloss travels the world sharing with audiences young and old the compelling story of surviving the Holocaust and rebuilding her life.

A recent New York Times documentary featuring Schloss’s involvement with a virtual Holocaust testimonial project, was among 10 Academy Award contenders in this year’s documentary short subject category.

“Eva is a courageous individual who works tirelessly to end the violence and bigotry that continues to plague our world,” says Rabbi Shlame Landa of Chabad of Fairfield.

Schloss spoke about her family’s relationship with the Franks and her experience in the Holocaust and its aftermath in her book, which includes an interview conducted in 2009. The following are excerpts of that interview.

Anne Frank (2nd from left), Eva Schloss (4th from left) and friends at Anne’s 10th birthday party (June 12, 1939).

Q: In early 1934, the Otto Frank family left Germany and moved into a home on the Merwedeplein in Amsterdam. Did you meet the Frank family when you moved there?

A: We arrived in Amsterdam in February 1940. We had our own apartment [on the Merwedeplein, the newly developed South Amsterdam neighborhood that had become a magnet for German-Jewish refugees], and we were together again as a family.

Anne Frank and I knew each other for about two-and-a-half years on the Merwedeplein. She was just month younger than I was. We saw each other every day after school because the children of the neighborhood would play together outside on the street. But Anne was more advanced and sophisticated than I was. She was quite a talker, and she liked telling her stories and being the center of attention. I was more shy at that time. Anne loved parties and she liked having a boyfriend; in fact, she was quite a flirt.

Q: Many Amsterdam Jews had gone into hiding by July 1942. The Franks and the van Pelses had eight people hiding together. But you and Mutti were separated from [your brother] Heinz and [your father] Pappy?

A: My father and Otto Frank decided to go into hiding in July of 1942, when about 10,000 young people received deportation orders – to be conscripted into labor camps. My older brother, Heinz, received that notice, as did Anne Frank’s older sister, Margot. That’s when our parents decided that it was time to disappear.

…We depended on brave Dutch people who were risking their lives to help Jewish people. Most people in the city lived in small apartments, so there was not enough room – and it was too risky – to take in a whole family. A family of four would have been too many. … There were sometimes more people hiding together on farms (as Heinz and Pappy were) simply because there was more room on the farms.

Q: The Nazis must have realized that many Jews had simply disappeared. How often did they come looking for hidden Jews?

A: There were house searches about every week. Before we were arrested, Mutti and I had to change hiding places seven times in two years. …. Mutti and I were not living with Pappy and Heinz during that time, but we were able to visit them sometimes because we could actually travel on trains: we did not look Jewish with our blond hair, and we had false papers as well. But one time when we went to visit them, we were followed from our hiding place, and it was a trap. We had been betrayed by a Dutch nurse who was a double agent. So all four of us were arrested at the same time.

Q: A very small number of Jews actually survived the concentration camps. But you, your mother did. What enabled you to survive?

A: Luck…luck…and more luck. Our family was deported to Birkenau in May 1944, and the Frank family was deported in August 1944. Had we been deported to the camps earlier, we would probably never have survived. Also, we did not have to wait until the end of the war to be liberated because we were free as of January 1945, when the Russians came. As it was, Anne and Margot Frank died of typhus; my brother died of exhaustion during the forced marches – and probably my father, too.

Millions of other people did not survive the camps and the death marches, and it’s good for folks to know about this because many do not realize what it meant. … We were waiting for death. Anyone who died before being summoned to be gassed was just one less person they had to kill. So they made life as difficult and terrible as possible. … When we were in Birkenau, many times I felt that my life was threatened, but I never gave up hope. If you thought for one second that you had no hope, you would soon be dead. So we remained too stubborn to give up hope.

Q: Though you refer to events in your story sometimes as “answers to prayer,” you describe your family as “High Holy Days” Jews rather than fully observant or devout. Did your experiences during the war change your faith?

A: Many people did lose their belief in the existence of God – including me. The only thing we could do unhindered in the camp was silently pray for life to return to normal, in my case for Pappy and Heinz to return. Unfortunately, those prayers seemed to be of no avail. So when I first came out of the camps, I was an atheist. But after the war was over and as time moved on, and I saw the wonderful things around me in nature, in the births of my children and grandchildren – well, I thought it’s all so wonderful, so marvelous, that there must be a higher being. I thought that life would be meaningless if I were just to live it out and say, “That’s it!”

I questioned whether it was God’s responsibility that the death camps existed. And I decided no, it’s our responsibility. God gave us free will, and it is up to us to choose between good and evil. When I reflected more on my whole experience and my survival, I became a believer again, a very committed Jew. I realized that we did survive – against all odds. No Jew was supposed to have survived. But our race and people did survive! I believe that we have a special task to fulfill in this world, which is till now a mystery. But one day God will show his face again.

Q: After Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated, you and Mutti were back in Amsterdam. Is that where you reconnected with Otto Frank?

A: Otto had learned of his wife’s death on the trip to Odessa that those of us who had been liberated from Auschwitz had taken. But it was not until we were all back in Amsterdam that he learned of the death of his daughters. Otto had tracked down a woman who had been at Bergen-Belsen when Anne and Margot died. When Otto first came to our house, it was to tell us that terrible news. He was just devastated.

Otto returned a few days later with a parcel under his arm; he opened it very carefully and lovingly. It was Anne’s diary, and I remember that scene very clearly. Otto could only read a couple passages from it before bursting into tears. It was too emotional an experience for him. But the diary was really a lifeline for him, because before that he was in a desperate state; but through the diary, he found that Anne was still really with him.

Q: You have said that you were very bitter and full of hatred for 20 years after your survival of the camps. How were you able to break that cycle and rebuild your life?

A: It took a very, very long time for me to get over my depression, my hatred of the Nazis and my suspicion of people in general. Otto Frank started coming to our home very often, to talk with Fritzi (Mutti) and me, and to help my mother with me. I was a very sad teenager, very difficult. I couldn’t live an ordinary life – couldn’t make friends – and he was a childless father, a man who had lost everything that was dear to him in life. So we all became very close.

…After finishing school, I left for England for a year, and I suppose my mother and Otto became even closer. They were married in 1953, a year after I got married, and were together for 27 years – until Otto’s death in 1980. And I’ve never seen a happier couple than those two. They really devoted their lives to the publication and aftermath of Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl (it was made into a play and a movie and was translated into 70 languages). When my mother died in 1998, I found copies fo 30,000 letters that they had written to people all over the world. That really was their life.

Q: What do you believe young people and adults can learn from your story?

Q: What do you believe young people and adults can learn from your story?

A: My story is Anne Frank’s story after her famous Diary ends. It is thus a sequel to Anne’s Diary, the story she could not tell because she died, but that I could tell because I survived. In telling the story of a girl of Anne’s same age and one of her playmates in Amsterdam, my story shows what would have happened to Anne – and did happen to the rest of us – after we were all betrayed and arrested.

I wrote my story in part to commemorate the lives of 12 million people all over Europe who were victims of the Nazi regime.

For ticket information regarding Eva Schloss’ talk on Sunday, Oct. 28, 5 p.m. at Klein Memorial Auditorium, 910 Fairfield Ave., Bridgeport, visit chabadFF.com.

For ticket information regarding the Monday, Oct. 29 talk, 7 p.m. at the Bushnell Theater, visit historic even.org or call (860) 232-1116.

The Connecticut Jewish Ledger is a media sponsor the Hartford event.

CAP: Anne Frank (right) plays on the Merwedeplein, the Amsterdam neighborhood that became a magnet for Jewish refugees, with her friends Eva Schloss (left) and Susanne Ledermann (center). Anne perished in Bergen-Belsen in 1945, and Susanne perished in Auschwitz in 1943, both at the age of 15.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger