“I believe that by studying Hasidism we can learn about the unique experience of Hasidism, but we can also learn something important about the universal human experience of spirituality.”

By Judie Jacobson

A native of Swidnica, Silesia, Marcin Wodzinski is a professor of Jewish history and literature, and head of the Department of Jewish Studies at the University of Wrocław in Poland. The scope of his academic interests and research focuses on Hebrew epigraphy, Jewish material culture, and the social and religious history of the Jews in 19th-century Eastern Europe, especially the history of Hasidism and the Haskalah.

A native of Swidnica, Silesia, Marcin Wodzinski is a professor of Jewish history and literature, and head of the Department of Jewish Studies at the University of Wrocław in Poland. The scope of his academic interests and research focuses on Hebrew epigraphy, Jewish material culture, and the social and religious history of the Jews in 19th-century Eastern Europe, especially the history of Hasidism and the Haskalah.

Wodzinski, who is not Jewish, has also spent extended periods of time at universities in Israel and the US and served from 2007 to 2014 as chief historian at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw.

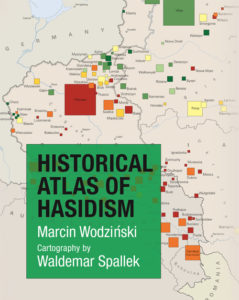

The author of more than 100 articles in Polish, English, Hebrew, French, and Czech, as well as 13 books (two of them co-authored), his most recent books are Historical Atlas of Hasidism (Princeton, 2018), Hasidism: Key Questions (Oxford, 2018), as well as Hasidism: A New History (Princeton, 2017), which he co-authored.

Dr. Wodzinski will deliver a lecture on “The Hasidic World: From Eastern Europe to Contemporary America” on Sunday, Oct. 7, 7 p.m., at The Emanuel Synagogue.

Recently, the Ledger interviewed Dr. Wodzinski about his groundbreaking research into the world of Hasidism.

JEWISH LEDGER (JL): How did you, a Polish non-Jew, develop so great an interest in Hasidism? Why would Poles, most of whom are Catholic, be interested in this subject?

MARCIN WODZINSKI (MW): I think there is a positive correlation between strength of Catholicism in Poland and relatively wide interest in Hasidism: unlike in history, many religious people today have a positive interest in the religious life of other religions. For people in Poland, this makes Hasidism an obvious object of interest, as Hasidism emerged in Poland, much of its history is intrinsically intertwined with history of Poland, and this might be today the one of the most important religious phenomena to historically develop in Poland ever – and I don’t mean only within the Jewish community, but of all religious phenomena.

Also, interest in Hasidism is simply a part of far more general interest in Jewish history and culture that from the 1980s has flourished in Poland. The Museum of the History of Polish Jews, opened three years ago in Warsaw, is today the single most popular museum in Poland. And every year at my alma mater, University of Wrocław, we accept up to 80 candidates for a BA in Jewish studies, in addition to several MA and PhD students. This is far larger than any Jewish studies program in Israel! [We don’t ask about their religion] and origin, but you might easily gather many of them are non-Jewish.

JL: Tell us about your new book, Historical Atlas of Hasidism – the first cartographic reference book on Hasidism. How does it contribute to an understanding of Hasidism?

MW: This is large format full-color book of 74 maps, 100 illustrations, charts, tables, and text that together attempt to show an overlooked aspect of the Hasidic movement, and a critically important aspect, in my opinion.

Quite often, both scholars and non-academic members of the public look at Hasidism as an intellectual phenomenon, they are interested in the teachings of the Hasidic masters and the philosophical or doctrinal traditions in Hasidism. This is certainly an important part of Hasidism, but not all of it. In addition, many people, following Abraham Joshua Heschel’s famous dictum, believe that Judaism, and Hasidism in particular, is a religion of time and not a religion of space. Especially for those who can’t differentiate between Ukrainian Bratslav, where Rabbi Nachman of Braslav lived, and German Breslau, this is an easy excuse to treat all of Eastern Europe as terra incognita. Together this creates an image of Hasidism that is unbearably elitist, aterritorial, and even ahistorical.

The atlas demonstrates how wrong this perspective is. It shows how the Hasidim lived outside of their leaders’ courts, how they prayed, how they were rooted in their places of residence and how their religious experience was informed by the spatial conditions of the place they lived in. In addition to these new insights, the atlas is methodologically innovative, addressed to a diverse group of readers, and at the same time visually striking. I hope it will change the way many people look at Hasidism, and hopefully at Jewish life and history more generally.

JL: Your book Hasidism: Key Questions has been referred to as a “radically” new way of looking at Hasidism. How so?

MW: In fact, Hasidism: Key Questions was published exactly the same month as Historical Atlas of Hasidism, July 2018, and it is a part of the same larger research project that I have run for almost 12 years. Now it bears fruit of three books, two of them just published and the third one in the pipeline. For these reasons, conceptual foundations of Hasidism: Key Questions are somewhat similar to those of the atlas. It stems from the criticism of dominant concepts of looking at and writing about Hasidism. First, as hinted, the attention of scholars was focused over the years mainly on the intellectual heritage of the Hasidic movement. In addition, scholars tended not to incorporate non-Hasidic, non-Hebrew, and non-Yiddish primary source materials. Also, they focused almost exclusively on the beginnings of the movement; until very recently 90 percent of the scholarship focused on the initial 10 percent of Hasidic history. And, finally, the majority of studies dealt with the Hasidic elite and treated it as an ahistorical, purely intellectual phenomenon.

By rejecting these assumptions, my book shows an essentially unknown image of Hasidism experienced and performed, and not only intellectually conceived; not elitist, but egalitarian (of course, with all pre-modern limitations of egalitarianism, i.e. with exclusion of the poor, women, and many other underprivileged groups) – as it developed over a long period of time from the late 18th century until today.

JL: And what makes this so radical?

MW: I presume it sounds too academic, doesn’t it? But guided by these principles I asked seven key questions regarding what Hasidism really was and how it really functioned. In short, my responses show a Hasidism that we don’t know. That is: Hasidism was not what you think; the place of women was different than traditionally assumed; from the perspective of rank-and-file followers, the role of a tsadik was significantly different than what we know about it; we have a very wrong impression of how many Hasidim there were in Eastern Europe over the centuries and where they lived; we have an equally wrong impression of the economic status of the Hasidim; and, finally, we misunderstand the end of Hasidism in Eastern Europe.

JL: Let’s follow on the last point. You maintain in this book that the end of Hasidism in Eastern Europe and its subsequent shift to the US and Israel actually began during World War I, and not, as many might assume, as a result of World War II. What caused it to wane during or in the aftermath of WWI? And did World War II further exacerbate its decline in Europe?

MW: Indeed. Today, the Holocaust has overshadowed that memory, but when one speaks of the end of the traditional Hasidic world in Eastern Europe, it actually ended with World War I. Take into consideration the usual atrocities of the war in addition to mass dislocations, exceptionally high casualties and material losses, destruction of traditional social structures, the rise of radicalism outside and within Jewish society, waves of pogroms, Bolshevik revolution and the subsequent anti-religious campaign in the Soviet Union. The world changed beyond recognition. In 1918 the American-Jewish journalist and ex-Hasid Yitzhok Even stated that “the relation of the war to the sudden decline of Chassidism is obvious.” He doubted “whether with the cessation of the war the Zadik will be restored to his former position.” He was right.

JL: What do you think is the major misconception people have about Hasidism?

MW: I think it is about Hasidism as a sect. This term is often used in relation to Hasidism and, for many, it unconsciously projects on Hasidism characteristics associated in popular discourse with sectarianism: dependency, intolerance, exclusiveness and secretiveness, separateness from and rejection of society, tension with the surrounding culture and society, narrow-mindedness, manipulative and brainwashing practices, irrational behavior, coerciveness. This is very wrong. What is worse, when one looks at Hasidism through the cognitive category of a sect, one fails to see what Hasidism really was. I claim that historically Hasidism was never a sect, but, if one looks for a structure of closest resemblance to Hasidism in traditional Jewish culture, it was a confraternity, a chevra.

JL: What in particular would you like readers to take away from your books?

MW: Today, I’d like them to walk away with the two books they buy! But seriously, I’m genuinely fascinated with Hasidism. It’s so unique, but at the same time so much resembles other religious phenomena across the world. I believe that by studying Hasidism we can appreciate both; we can learn about unique experience of Hasidism, but we can also learn something important about the universal human experience of spirituality, the ways people structure it, experience and perform it.

JL: What is your vision for the future of Hasidism?

MW: Difficult question. Historians usually focus on the past, not today or tomorrow. But the atlas indeed ends with two chapters on contemporary Hasidism. It also presents the first ever estimation of the demographic strength of the Hasidic movement today, which allows for some prognostics as to the future.

From a tiny group of Holocaust survivors, Hasidism has grown today into a significant sector of a Jewish society worldwide. But I think that those who are fearful of a Hasidic conquest are as erroneous as those who ignore its importance. The Hasidim make up today around five percent of world Jewry, the same in Israel and North America. It is somewhat higher in the UK or Belgium, but in general they are very far from anything close to a Hasidic dominance. What is more, their tendency to create enclaves, such as Kiryas Joel or Kaser, make their influence very localized.

At the same time, Hasidism more than any other religious phenomenon of modern Jewish history captures the imagination of contemporary, secular societies, Jewish and non-Jewish alike. For many, Hasidism is simply an embodiment of traditional Judaism and traditional Jewish culture. If I were to guess the future, I’d say Hasidism has a good chance of continuing both trends – namely, it will continue to play an important role in the consciousness of Jewish and non-Jewish public opinion and will continue to grow demographically, though without anything close to a demographic dominance, except for a few haredi enclaves.

At the same time, I predict Hasidism will continue to diversify internally, as it is visible already, and will grow an increasingly large gray zone of semi-Hasidic, post-Hasidic, neo-Hasidic or near-Hasidic identities and social roles.

Most importantly, however it develops, it will continue to be a fascinating phenomenon.

JL: Before we end, let’s touch on another topic. What is your take on the rising tide of antisemitism in Poland today that seems to be an outgrowth of the conflict regarding the participation of many Polish people in the persecution of their Jewish neighbors during the Holocaust?

MW: You might be surprised, but I’m not especially concerned about the rise of antisemitism in Poland today. What you refer to is the outcome of the huge debate that changed the Polish discourse over last 18 years. Initiated by Jan T. Gross’ book Neighbors, it made a huge impact on the way Poles look at themselves. Naturally, it polarized opinions. For some it showed an ambivalence regarding the past. Some others, agitated by the blunt generalizations implicit in your very question, developed defensive strategies of rejecting the historical truth. Still, some others developed antisemitic sentiments. I was shocked when an antisemitic activist burned an effigy of a Jew at the market square of my hometown. But I was equally heartened by the public reaction to this act. Altogether the Polish society over the last 18 years did far more than many others to learn about their dark past and to redefine itself. What was truly worrying was the way the Polish state authorities avoided outright condemnation of the incident.

JL: So what are you concerned about if not the rise of antisemitism?

MW: As I said, what worries me today is not the rise of antisemitism itself, but the broader phenomenon it belongs to. A tide of populism, chauvinism, xenophobia, and authoritarian tendencies is visible worldwide, including the US and Israel, but Poland seems to be struck by it especially heavily. What you might have heard of as the Holocaust bill passed by the Polish parliament in February this year, actually subscribes to this wider tide. Both American and Polish state politics belongs in some way to this trend, too. I’m most concerned where it will bring us.

Dr. Marcin Wodzinski will discuss “The Hasidic World: From Eastern Europe to Contemporary America” on Sunday, Oct. 7, at 7 p.m., at The Emanuel Synagogue, 160 Mohegan Dr., West Hartford. The program is co-sponsored by Beth David Synagogue, Congregation Beth Israel, Trinity College Jewish Studies, and Young Israel of West Hartford. Light refreshments will be served. Dr. Wodzinski’s talk is free and open to the public. Reservations are requested. Contact Gail Adler at gailadler@aol.com.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger