Remembering Stacy Phillips

By Paul Bass

Reprinted with permission of New Haven Independent (www.newhavenindependent.org).

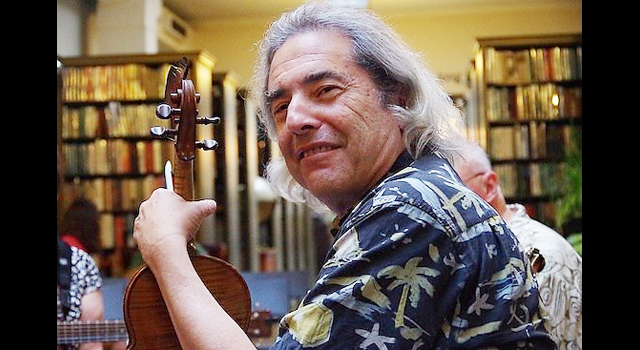

Watching Stacy Phillips contemplatively smoke his cigars in baggy pants and a T-shirt outside his Alden Avenue apartment in New Haven or pass the hat between sets with his “bluegrass characters” at the Outer Space, you might not guess he won a Grammy.

You might not know that he played with some of the leading lights of the acoustic music revival of the 1960s and 1970s. You might not guess that he wrote books on music or that he had spent decades studying the intricacies of musical genres ranging from Hawaiian to hillbilly, from klezmer to gospel, from Ukrainian to Middle Eastern. You might not know that he was considered a master of the Dobro guitar on top of playing a mean fiddle.

Stacy Phillips didn’t consider himself a big shot. He scraped together a living here, gigging with multiple New Haven-area ensembles, teaching students, and writing books for more than three decades. With an easygoing demeanor that masked an intense commitment to the highest standards, he kept old-time music alive, imbuing it with new meaning. And he inspired fellow musicians and roots-loving audiences alike.

That all came to an end Tuesday, June 5, when Phillips died in St. Francis Hospital in Hartford after lying in a coma for three days, according to bassist David Chevan, whom the family designated to speak publicly about the death. Phillips was 73 years old.

Phillips had just finished playing a gig at West Hartford’s Emanuel Synagogue Sunday with the Afro-Semitic Experience, a group he and Chevan cofounded with pianist Warren Byrd and other musicians. He was hurrying to a bluegrass gig in Old Lyme with Nick Anderson and Shady Creek when he pulled over his car “and had a massive heart attack,” according to a notice Chevan said via email Tuesday. Rushed to St. Francis, he was put into an induced coma.

“Once his family was all together he was taken off life support. He died surrounded by his closest family,” Chevan wrote.

Phillips donated his body to Yale Medical School. No funeral was planned, but Chevan organized a “musical memorial” to him that was held on Sunday afternoon, June 10, at Cafe Nine.

Phillips never amassed riches, at least not financially. But he cultivated a lifetime’s worth of rich musical experiences that he shared with countless others.

“There is a hole in my soul now that Stacy is gone,” Yale University President Peter Salovey told the Independent.

Salovey, a bluegrass bassist, was a graduate student when he met Phillips at a bluegrass concert in the 1980s. They became friends and jammed together. Even after becoming Yale’s president, Salovey annually dropped in for a few numbers during the annual Christmas Eve concert put on (for a mostly Jewish audience) at local spots by Stacy Phillips and His Bluegrass Characters, a fluid ensemble of regular players Phillips headlined the last Tuesday of every month at Best Video and the old Outer Space. Phillips played at his friend Salovey’s presidential inauguration at Yale.

“Stacy was the most gifted musician I have known,” Salovey reflected. “On both Dobro guitar and fiddle, his virtuosity could be appreciated in so many different genres and styles. Stacy was generous as a teacher and advisor to so many Yale students, converting them from classically trained violinists to creative and improvisational Appalachian fiddlers.”

Mandolinist Phil Zimmerman performed off and on with Phillips since they met in 1972, most recently in the Bluegrass Characters. Tuesday night he recalled how Phillips “would have us rehearse harmony parts note by note. He’d pick apart a song, pick apart an arrangement, just bring it to life.”

“He had a way of bringing musicians together and taking the ingredients and stirring them up and making a real cohesive,” Zimmerman said. “He had very high standards. He pushed his bandmates hard. He pushed himself harder. His greatest joy was making good music.”

“As a Dobro player, I think he was just the best in the world, no exaggeration,” said jazz saxophonist and composer Allen Lowe, one of the many veteran musicians who performed and recorded with Phillips. “Just a sweet and funny guy, quick-witted on the bandstand and off, a real old-school Yeshiva boy.”

Chumash, Chemistry Didn’t Take

Stacy Phillips was born on Sept. 29, 1944 – not as Stacy Phillips, but as Melvyn Marshall. He later adopted Stacy Phillips as his stage name.

He grew up in Washington Heights, then a tough neighborhood in upper Manhattan. He sometimes got beat up in public school. His family switched him to Jewish day schools, first Yeshiva Rabbi Moses Soloveichik (named after a relative of Peter Salovey, coincidentally), then Yeshiva University High School. His parents kept kosher but didn’t accompany him to shul on the Sabbath.

After switching schools, Phillips still had to worry about being attacked in the neighborhood. “It got to the point where I wasn’t sure I would make it through each day. It was rather dangerous,” especially around Christmas and Easter when Christian neighborhood toughs preyed on Jewish kids, he recalled in a 2016 interview on WNHH FM’s “Chai Haven” program. “That was one of the things that made me feel Jewish – I was beaten up. Humiliated. It was dark at night at Christmastime. At Yeshiva High School, I would start studying at eight in the morning. I would come home at seven at night. I would be walking home carrying 25 pounds of gemaras and chumashim …. with my tzistzis hanging out.”

Phillips didn’t come from a musical family. He didn’t pick up instruments in his teens, the age when many musicians get their start. He studied to become a chemist at the then-named Polytechnic Institute.

The studies didn’t take. “I was thinking I’d wind up being a career criminal, because I didn’t like what I was doing. I was a lousy chemist,” he recalled.

The folk music revival was going strong in New York at the time. His junior year, “a friend of mine got himself a guitar and taught himself to play. I thought, ‘Holy cow! That is possible to do?’” Phillips got a guitar too. He discovered he had talent.

At some point he was playing at a party, and a fiddle player active in the scene named Kenny Kosek noticed that Phillips had talent, too. He invited Phillips to perform with him.

That led Phillips to learn the fiddle as well. And it landed him in the Breakfast Special, a breakout acoustic roots group that recorded an iconic record for Rounder in 1977. (Rounder reissued it in 2011.) The group included banjo player Tony Trischka and mutli-instrumentalist Andy Statman, who remain nationally renowned musicians to this day. Back then, bluegrass was just beginning to enjoy its own revival. Breakfast Special delved into gospel, country western, jazz, New Orleans rock ‘n’ roll – and an Eastern European Jewish-derived music known as klezmer, which would soon undergo a revival of its own.

Voice Of The Dobro

Phillips settled in the New Haven area in the 1980s. He became a regular at clubs and outdoor concerts, playing with an endless roster of musicians. He had a loose onstage style with old-timey between-song shtick (like one memorable story about a Lower East Side man who kept getting spooked by a talking majtes herring) that matched the old-timey song lists drawn from bluegrass masters like Bill Monroe and Lester Flatt. Between the banter and the improvisational playing, audiences learned a lot about those masters and the roots of the music.

Phillips made his reputation most with his mastery of the Dobro, a resophonic acoustic guitar with a steel belly played with a slide and often placed on the musician’s lap. He recorded an album dedicated to the instrument, tailoring songs from a range of genres from Hawaiian to gospel to Jewish liturgical music to what was usually thought of as a country music tool. He also wrote an instruction manual for Dobro players.

“It’s the instrument I express myself best on. In a sense it’s my voice,” he said. “I’m not much of a singer. The instrument functions as that.”

In addition to two other solo albums, Phillips joined other musicians considered the top players of the instrument on the 1994 collection The Great Dobro Sessions. That album won a Grammy for best bluegrass album, even though, Phillips noted, “it didn’t have very much bluegrass in it.”

The album’s producers, Jerry Douglas and Tut Taylor, got the Grammy statue. Phillips received an embossed certificate. He gave it to his mother, who framed it. In time it returned to him. But he didn’t hang it on his wall.

“The awards I won – I would lose them if I didn’t put them in a central place,” he said. “Which is my freezer.”

Why the freezer?

“Because there’s space there.”

The Grammy did not change his life or lead to fame. “It’s a lot better than not having it,” he’d say with a shrug. “But the reality is a lot of great musicians haven’t won Grammies.”

In addition to headlining the Bluegrass Characters, Phillips at the time of his death played regularly in a duo with Paul Howard, with a Hawaiian music trio called Three Finger Poi, with the old-timey country Heroes of Tradition, in a traditional Irish music duo with Joe Gerhard, in a contra dance combo called The Fascinating Swivets, and in the groundbreaking ensemble The Afro-Semitic Experience, in which African-American and Jewish musicians play updated versions of gospel and Jewish liturgical songs. That group has recorded memorable albums and played often in local churches, synagogues, and other venues. Phillips was a founding member.

Playing in that group for the past 25 years enabled Phillips to remain in musical touch with his Jewish roots; while he didn’t grow up to be religiously observant, he retained a strong Jewish identity expressed through the music.

“He brought a lot to the table, including a prickly personality that grated on everyone’s nerves at some point or another,” co-founder David Chevan recalled. “He was difficult because he was a demanding perfectionist and loved rehearsing and working on parts. Some of the best transcriptions of old Eastern European Klezmer melodies were made by Stacy. He put a lot of time and effort into that work.”

Phillips joined Chevan in founding another ensemble, Nu Haven Kapelye, dedicated to klezmer music. This became a community orchestra full of volunteers. Phillips wasn’t just a lead player. He was a mentor to many in the group, Chevan recalled.

“We often have very young musicians, some as young as 10 or 11, playing alongside their elders,” Chevan said. “Year after year Stacy would find a way to bolster the confidence of the youngest, newest members of the group and encourage them and show them how to play their parts. He would often write little arrangements just for those beginning klezmer musicians.

“Yes, Stacy could be really gruff, but he was 100 percent about the love of music and music making, and what he shared with those young players had an impact. Often when I was working on a difficult passage with another section of the Kapelye he would work on violin parts with the rest of the violinists.”

Phillips’ Dobro was highlighted in some of the Afro-Semitic Experience’s most memorable recorded tracks, such as “Ani S’filosi” on the Days of Awe collection reinterpreting classic melodies from Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services. It begins with Phillips playing solo, on one string, extracting and bending each note from deep inside his soul the way supplicants beseech the Lord for one last forgiveness before the Gates of Heaven close for another year. On such tunes, Phillips said, the Dobro becomes “the small still voice. It could be my voice, alone in the universe. Or me and the maker dealing one on one.”

You can hear Phillips play a beautiful rendition of “Shalom Aleichem” and then discuss it at the beginning of a radio interview at: https://soundcloud.com/new-haven-independent/chai-haven-dobro-inspiration-unconventional-torah-advice-the-rabbi-the-reverend

Phillips’ Dobro also adds a new twist to the gospel classic “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free” (the Afro-Semitic track that closes each episode of WNHH FM’s daily “Dateline New Haven” program).

“Play It Again!”

Some of Phillips’ most memorable performances came as a sideman to bigger names. In 2008, for instance, David Bromberg called him onstage at the Little Theater on Lincoln Street. Blown away by Phillips’ playing, Bromberg called out, “Play it again!” Which Phillips did.

Tony Trischka invited Phillips onstage to take the Dobro lead on “Nashville Skyline” during a show at Cafe Nine dedicated to Bob Dylan tunes.

Phillips’s former Breakfast Special bandmates Statman and Trischka came to New Haven in 2016 to reunite onstage with Phillips at the Outer Space Ballroom. They played for hours, old friends picking up where they’d left off in New York in the 1970s. Statman and Trischka were the big names, the official bluegrass stars of the night. But everyone in the room, including them, knew that the now gray-maned Stacy Phillips, bending over his Dobro and sliding up and down the strings, was right up there with them.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger