By Cindy Mindell

Mrs. Kaufmann Nussbaum (pictured in 1955) was one of the founding members of the Deborah Society, the oldest society of women in Connecticut. Formed in 1852 by a group of German-speaking wives of Beth Israel members, the society served the Jewish community for 136 years, providing religious, social and philanthropic functions. Photo credit: Marjorie Rafal, The Way We Were 1843-2001.

WEST HARTFORD – Connecticut is home to more than 100 Jewish congregations, from full-time synagogues and Chabad houses to chavurot and other groups that meet weekly or monthly or only during the summer, to onsite sanctuaries in senior-living communities.

The point is, finding a Jewish worship service in Connecticut is not a major challenge. So, to a 21st-century Jewish Nutmegger, it might seem amazing that the state spent most of its first two centuries as a theocracy, with the Congregational Church as the official religion. Other Protestant sects were not considered equal until 1818, and Jewish public worship was specifically excluded by law – even though court records indicate that there were Jews living in Hartford as early as 1659.

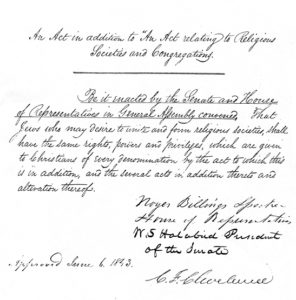

All that changed in 1843, when the three-year-old Congregation Mishkan Israel in New Haven, a “society for the worship of God,” sought to purchase land for a cemetery and approached the Connecticut General Assembly. In “The Petition of Louis Rothschild and Others for Certain Religious Privileges,” the group requests that the legislative body “take our cause into consideration and grant us relief in this case by giving us the same privileges and immunities as are now enjoyed by Christian societies of all denominations, which we, being Jews, do not now enjoy.”

After some back-and-forth among various committees, the General Assembly eventually passed a Special Act, declaring “that Jews who may desire to unite and form religious societies shall have the same rights, powers, and privileges which are given to Christians of every denomination.”

The Jewish communities of New Haven and Hartford wasted no time: Congregation Mishkan Israel immediately purchased land in Westville to establish a cemetery, still in use today, and formalized the temporary worship space above a store in downtown New Haven as a synagogue. In Hartford, a group of German-Jewish immigrants established the Orthodox Congregation Beth Israel, meeting in members’ homes until 1876, when the newly-built synagogue at 21 Charter Oak Avenue opened its doors.

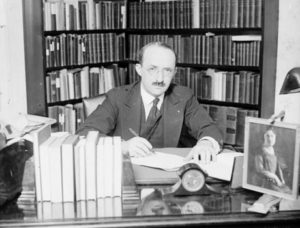

The officially recorded first meeting of the congregation was held at the home of A. Rothenberg on Sheldon Street in downtown Hartford. Members, including Gerson Fox (pictured above), Alexander Rothschild, Aaron Blumenthal, Meyer Stern, David Engel, and Moses Ballerstein collected dues and elected officers, including their first president, Meyer Stern, and their first sexton, David Engel.

This shared 175th anniversary – of the Special Act extending religious freedom to Connecticut Jews, and of Congregation Beth Israel – will be celebrated on Wednesday, June 6 at Hartford’s Old State House.

The event is co-sponsored by Congregation Mishkan Israel, which celebrated its 175th anniversary in 2015; Charter Oak Cultural Center; Hartford Seminary; Connecticut Council for Interreligious Understanding; Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford; and Connecticut Historical Society Museum and Library.

The first Jewish congregation established in Hartford, Beth Israel joined with other American Reform Jewish synagogues in 1877 to form the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (now the Union for Reform Judaism), an umbrella support organization.

Rabbi Abraham Feldman came to the Beth Israel pulpit in 1925, and would lead the congregation until 1968, when he became rabbi emeritus. (Rabbi Feldman also co-founded the Jewish Ledger in 1929.) In 1936, the congregation moved to its current location at 701 Farmington Avenue in West Hartford, a building designed by architect Charles R. Greco and listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1995. Feldman was succeeded by Rabbi Harold Silver, a third-generation rabbi and the nephew of the influential American Zionist leader, Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver. After Harold Silver retired and became rabbi emeritus in 1993, Rabbi Simeon Glaser led the congregation for four years, followed by Stephen Fuchs, who became rabbi emeritus in 2011. Beth Israel is currently led by Senior Rabbi Michael Pincus and Assistant Rabbi Andi Fliegler.

The 175th anniversary has kicked up a bit of friendly competition between the Hartford and New Haven Jewish communities.

“There’s a long-running debate as to who is the oldest; it depends on your definition,” says Pincus. “Mishkan Israel was the one who filed the request because they wanted a place to bury their dead. Beth Israel was a group holding meetings and wanted to buy property for a synagogue.”

And while Connecticut scholars haven’t been able to unearth the names of the “Others” cited in the 1843 petition title, Beth Israel historian Jane Zande is pretty sure they included Hartford Jews.

“We assume that Beth Israel was involved because we were already in Hartford – close to the General Assembly – and we were already meeting as Jews and creating community,” she says.

The idea to involve other congregations and community organizations came from Gail Mangs, chair of Beth Israel’s 175th anniversary planning committee.

“It’s a big milestone for our congregation but in light of what’s going on in our world today, we wanted to bring it to a broader spectrum and talk about religious freedom,” Pincus says. “We wanted to expand and so we reached out to a number or organizations that work to broaden that expression of religious unity and get across the message of religious understanding for everybody.”

Many people might find aspects of the state’s history “shocking,” Pincus says: not only that it took until the mid-19th century to grant Jews religious freedom, but that Protestant sects other than the Congregationalists were banned until 1818, and the General Assembly did not ratify the Bill of Rights until 1939.

“And yet, Connecticut is seen these days as one of the most liberal, open-minded states in the country,” Pincus says. “So I think it’s interesting to shed light on that and reflect that even in this state, we’ve come a long way and we still have a long way to go. We should be very thankful that we live in a place where everyone can practice their religion as they wish to.”

What might the next 175 years look like for Beth Israel?

To learn more about Congregation Beth Israel’s first 175 years, visit the history timeline in the synagogue lobby, 701 Farmington Ave., West Hartford or online at cbict.org.

“Beth Israel was very ‘Classical Reform’ in the ‘40s and early ‘50s, and we discarded some Jewish traditional practices until the ‘60s, like bar mitzvah, the wedding chuppah, and kippot – all of which we have reintroduced,” Zande says. “We continue to reach back to our traditions and bring them into our worship services and the way we practice Judaism. At the same time, we’re looking forward, creating new styles of worship services that both include traditional rituals and introduce new aspects, like music and holding services in natural settings. Another thing we’re doing is strengthening our relationships among each other and being more welcoming to interfaith families, Jews by choice, and the LGBTQ community, so we’re reaching out to a much more diverse range of Jewish people.”

Five years ago, on the occasion of Beth Israel’s 170th anniversary, Pincus told the Ledger, “Our community grows ever more heterogeneous and complicated. And yet, the very reasons that this synagogue was first founded have not changed: to be there for each other in good times and in bad, to learn, to grow, and to make this world a better place – these are the reasons this community was founded and what we hope to continue to be.”

Today, Pincus sees the congregation continuing its long legacy of social action, civic engagement, and interfaith bridge-building that has been part of the Beth Israel culture since the 1930s.

“I think that we are more and more working together to transform the privileges and rights that the law provides into relationships and partnerships,” he says. “I hope that we’re going to continue to build those relationships and partnerships.”

Congregation Beth Israel celebrates 175 years of Jewish religious freedom in Connecticut: Wednesday, June 6, 6 p.m., Old Statehouse, 800 Main St., Hartford; Seating is limited; $5 parking is available for the State House Square Garage, 55 Market Street; bring your ticket to the Old State House for validation. Info: cbict.org, (860) 233-8215.

The historical background in this article was culled from “The 1843 Petition: Gaining Religious Freedom for Connecticut Jews,” a lecture delivered by architectural historian Mary M. Donohue at the Old State House in Hartford in May 2016 and broadcast on Connecticut Network. Donahue is the assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger