Lemba leader in Fairfield Nov. 18

By Cindy Mindell

Lemba tribal leaders in Zimbabwe and South Africa – also known as the Black Jews of Southern Africa – have long claimed to be descended from Jewish traders who traveled to Africa from Israel via Yemen many generations ago. A 1999 DNA study confirmed a Jewish genetic marker, and the Lemba’s Judaic-like customs set them apart from neighboring tribes: kashrut, male circumcision, a weekly holy day, belief in one God, and marrying within the tribe.

Recently, advanced DNA research has identified a priestly “Cohen” haplotype gene in more than 50 percent of all males in the priestly Buba clan, equal to or higher than the percentage of Cohanim in Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jewish groups around the world. According to Lemba oral tradition, it was the Buba who led the Lemba out of Israel.

Modreck Zvakavapano Maeresera is the president of the newly established Harare Lemba Synagogue, where he leads Shabbat services and promotes Jewish education in Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital city. A Shabbat-observant Jew, he has added a translation of Shona, the main language in Zimbabwe, to the English-Hebrew Shabbat prayerbook, and is working on a new Hebrew-Shona version.

Maeresera will speak at Congregation Beth El in Fairfield on Wednesday, Nov. 18.

“Growing up in a Lemba community, one is taught to embrace Lemba, culture, traditions, and values from an early age,” says Maeresera, now 40. “I was taught that I was different from other tribes and I was made to take pride in my being Lemba. Behaving in a way that was unbefitting of a Lemba boy would attract an admonition from the elders, who would point out that I was behaving like a Musenzi or non-Lemba. Not washing hands and face as soon as I woke up, not washing hands before eating, not being respectful to elders were some of the behaviors the elders pointed out as non-Lemba behavior. I was taught from an early age not to eat at other people’s houses or even sleep in non-Lemba houses to avoid violation of kashrut laws.”

Maeresera says that the Lemba had “a very cordial relationship” with their non-Lemba neighbors. For example, Lemba traditionally kept large herds of cattle, used in Zimbabwe to till the land. The Lemba would loan oxen and cows to non-Lemba for plowing and milking; in return, the non-Lemba would help weed the Lemba fields. In fact, most non-Lemba neighbors kept kosher, and would call on the Lemba to slaughter a chicken, goat, or cow. “This they did because they valued our friendship and wanted to maintain a cordial relationship with us,” Maeresera says. “Growing up, I never saw a pig in the neighboring non-Lemba villages. They didn’t keep pigs because they knew the Lemba loathed them.”

This relationship varies from location to location. “In some non-Lemba communities, especially those that live far away from Lemba communities, our customs are viewed as strange,” Maeresera says. “In some areas, we are even stigmatized as hard-headed and miserly Jews. In some districts, circumcised people are stigmatized as argumentative and stubborn. So it varies from place to place.”

Jews visiting a Lemba village from outside the Lemba community would encounter familiar Jewish practices and traditions, Maeresera says, including kashrut, the celebration of holidays like Rosh Chodesh, Rosh Hashana, and Yom Kippur, and marriage customs.

Maeresera began taking on leadership roles in his Jewish community as a teen, when he was the shochet (Jewish ritual slaughterer) for his school. He later served as secretary of the Lemba Cultural Association in South Africa. Maeresera earned a diploma in journalism and media studies from the Institute of Commercial Management, based in the UK, and is a recruitment and screening officer for Legenda College in Malaysia. He and his wife, Brenda, have two sons, Aviv and Shlomo.

Now, in addition to his work in Harare, Maeresera travels south to the Lemba village of Mapakomhere to help with Passover seders and other holiday celebrations, and to the Zimbabwean countryside to support the more rural Lemba communities in establishing their congregations. Maeresera is compiling a Lemba Haggadah that will include the Lemba story as well as the traditional Passover story.

Traditionally, the Lemba have lived in village communities, where it is easy to maintain and keep their culture and traditions. As Lemba (and others) increasingly migrate to cities to seek work, Jewish life can be more difficult to sustain.

“A good example is that we have no kosher butcheries [in Harare], so we end up not eating beef,” Maeresera says. “If we need meat, we buy live chickens to slaughter. We also live apart from each other, not in communities, and that makes it hard for the city Lemba to maintain our identity.”

He is on a U.S. speaking tour with Kulanu (Hebrew for “All of Us”), a New York-based non-profit organization founded in 1994 to support isolated and emerging Jewish communities around the world, many of whom have long been disconnected from the worldwide Jewish community. He has written a series of articles on Lemba history and tradition for Kulanu’s blog.

“My vision is to have a vibrant Lemba community that is fully committed to observing Judaism, the religion of our forefathers, and to have the necessary infrastructure that a Jewish community would need – synagogues, schools, and religious leaders,” says Maeresera. “In the near future, I hope the Lemba will be fully reintegrated into mainstream Judaism.”

The Fairfield stop was organized by Justin Beck, chair of adult education and Israel advocacy at Congregation Beth El, and co-hosted by Congregations B’nai Israel and Rodeph Sholom (Bridgeport), Congregation B’nai Torah (Trumbull), and Congregation for Humanistic Judaism of Fairfield County.

“Since the times of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and culminating with the life-altering event with Moses at Mount Sinai, humanity has been programmed to rediscover our unified connection with our Creator,” says Beck. “Each and every individual, from every culture across the globe, has a unique and important role to play in this process. It is imperative, now more than ever, that we recognize the value of every soul and their special gift. We are pleased to host our honored guest from the Lemba tribe in Zimbabwe, who will share and enlighten us, bringing us one step closer to our ever-expanding world consciousness, to a harmonious existence.”

Modreck Maeresera will speak on Wednesday, Nov. 18, 7:30 p.m., at Congregation Beth El, 1200 Fairfield Woods Road, Fairfield. For information: congbethel.net / (203) 374-5544. Admission is free.

Comments? email cindym@jewishledger.com.

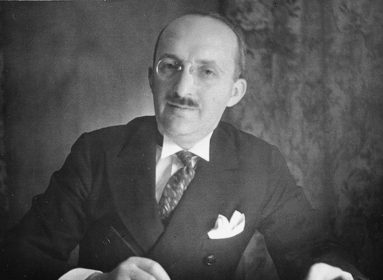

Modreck Maeresera

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger