By Paul Bass

The following is an excerpt of a story reprinted with permission of the “New Haven Independent” (www.newhavenindependent.org).

Old and New Testament verses converged inside a federal courtroom Friday, Jan. 16, as a judge sentenced a leader of one of New Haven’s largest-ever mortgage-fraud rings to 22 months behind bars — less than half the time given to co-conspirators who pocketed far less money.

The difference: The other co-conspirators fought the government. The leader sentenced in U.S. District Court on Church Street Friday, Menachem Yosef “Yossi” Levitin, spent four years helping the government find, then prosecute, his former allies.

By his own estimate, Levitin, who is 29 years old, pocketed up to a half-million dollars in broker’s fees on more than 40 sham property sales from 2006 to 2008. Levitin and allies created fake forms and falsely inflated the true sales prices, then collected mortgages based on the inflated prices and split the proceeds. The sham deals cheated lenders out of $7 million, according to the government. They also left behind a trail of blight in Newhallville, the Hill, and Fair Haven during last decade’s Great Recession.

Levitin faced more than eight years and $20 million in fines for his committing mail fraud, wire fraud, and bank fraud in connection with the scam. He pleaded guilty to those crimes.

On Friday, hours before the onset of the Sabbath, Willie Dow, the attorney for Levitin, an Orthodox Jew, appealed to U.S. District Court Judge Janet Hall to limit the sentence to a year and a day.

Dow called his yeshiva-trained client “the personification of the prodigal son” in the New Testament. Levitin is the sixth of 10 children of a respected New Haven Chasidic rabbi. As relatives and friends in black hats and yarmulkes silently recited psalms in the court pews, Rabbi Berl Levitin of Norton Street pleaded with the judge for leniency. He said “moschiach” — the messiah — is on his way, and good can come out of this sad episode.

“Your honor, I believe you’re an agent on earth of the court on high,” he told her.

“My son never stopped praying,” even when he strayed, Rabbi Levitin said. He said his son has since pursued the Yom Kippur liturgical proclamation that yeshivah, tefillah and tzedekah — Hebrew words for repentance, prayer, and righteous deeds — can avert bad “decrees.” The son dabbed his tearing eyes with a tissue as the father described growing closer to him during his ordeal and seeing him become not just honest, but “extra honest” in his business and charitable dealings.

Yossi Levitin spoke briefly, too. “I’m completely ashamed of my actions” and the shame it brought to family and community, he told the judge. Today, he said, he considers himself a changed man, “an ethical and moral businessman.”

The government, too, asked the judge to “depart below” the 78-to-97-month range federal sentencing guidelines suggested.

Throughout Friday’s session, a catch-22 was on display: The government sometimes makes its strongest case against members of a criminal conspiracy by offering leniency to the person who led or benefited most from the conspiracy — because that person can furnish crucial evidence. To lure conspirators to participate, the government agrees to submit “5K motions” to ask judges to depart from sentencing guidelines. That means the leaders can spend less time in jail than equally or less culpable people.

As Judge Hall put it Friday, “cooperators are often like Mr. Levitin. They have a very large role [in the crime]. That’s what makes them good cooperators.”

Hall said she struggled with arriving at a sentence that balanced society’s need to punish fraud — a “serious” crime that undermines the economic system and, in this case, contributed to the collapse of the housing market — with Levitin’s invaluable help to the government in locking up his accomplices.

“You’re obviously a good person,” Hall told him. She said the presence of so many family members and friends in the courtroom “signals” the support he has to remake his life: “What they’re saying to you is, ‘You’re a good enough person that I’m here for you today, and I’ll be here for you in the future.’

“The challenge for me is to weigh the extensive scope of your participation in this crime against the rest of your life — and in particular your assistance to the government.”

She then sentenced Levitin to 22 months in a minimum-security federal prison followed by five years of supervised release; at Dow’s request she agreed to let him wait until after the Passover holiday to surrender. She also ordered Levitin to pay $2.6 million in restitution on top of the $1.6 million to $1.8 million he has already forfeited to the government in cash and properties.

“This was a very difficult decision,” Hall told Levitin. “You’re much more than the offense that brings you to court today.”

Crash Of A High-Flyer

The story that brought Levitin to Hall’s courtroom resembles the cautionary tales of canonical literature.

Before reaching the age of 30, Levitin rose higher and sank lower than many hustlers twice his age. In his teens Levitin dropped out of a series of religious schools and began dealing in real estate. Riding around town on a motorcycle, wearing dark glasses, he rose to the heights of New Haven’s lucrative poverty-landlording and property-flipping world, learning along the way how to recruit and work the lawyers, buyers, and loan officers to create sham deals and steal millions of dollars from mortgage lenders. He and his accomplices arranged to snap up properties, then forge documents to pretend the properties sold for more money than they actually did. They obtained mortgages based on the inflated fake prices, split the proceeds, then largely left the properties to rot and struggling neighborhoods to contain the damage. The government identified at least 40 such transactions from 2006 through 2008. Levitin lured lawyers and strawbuyers, among others, into the conspiracy.

Then, in 2010, the feds busted the ring and arrested Levitin. He pleaded guilty in 2012. From 2010 to 2014 he held two dozen meetings with prosecutors and testified in court against his former co-conspirators in return for a lighter jail sentence for himself.

Thanks to Levitin’s help, his co-conspirators — some of whom made less than 1 percent of the amount Levitin pocketed in the scams — are sitting in jail or are heading there.

The feds kept their end of the bargain. The government asked Judge Hall to reduce the sentence based on his “pivotal” role in their prosecutions of the rest of the ring.

“His substantial assistance to the government that began three months after his arrest helped the government understand how the scheme was formed, who was responsible for what elements of the conspiracy, and what actually happened during key junctures in the conspiracy,” the U.S. Attorney’s Office wrote in its sentencing memorandum to Judge Hall.

Despite Levitin’s admitted fraud and thievery, the government allowed him to return to rebuilding his real estate empire in New Haven during the four years he met with them to prepare their cases against his accomplices. Even before he served any time. The feds did require him to forfeit an estimated $1.6 million worth of properties and cash before rebuilding his empire.

A Pious Childhood

Dow cited Levitin’s continued landlording as evidence that he has turned his life around. One of Levitin’s Newhallville tenants, Nina Fawcett, showed up in court Friday to tell Judge Hall that Levitin has helped accommodate her special-needs son and provided water to neighbors’ greenspace.

In his remarks in court as well as in his sentencing memo to Hall, Dow also walked a line between not seeming to excuse Levitin for his years of premeditated white-collar crime and limiting his role compared to that of his co-conspirators, and perhaps even the lenders Levitin bilked.

“The 29-year-old man who appears for sentencing is far different from the young property manager who was instructed in a method for buying and selling real estate almost a decade ago by two men twice his age. Young and unschooled, Joseph Levitin was proved a template skewed to take advantage of the lax lending practices which existed in the first decade of this century,” Dow wrote in his sentencing memo.

Dow offered a detail-rich version of Levitin’s “unique” upbringing in Beaver Hills, one that portrays Levitin’s turn to a life of crime almost noble, or at least the course that practically anyone would consider pursuing.

“His home had no television, video games or internet access. Family life and activities revolved around their faith and living their faith. There was neither concern nor desire for material possessions, almost to a fault. The house was not well maintained due to limited resources. Foreclosure notices were not unknown. Better Homes and Gardens was neither the aspiration nor the reality….”

That “life was not for” Levitin, Dow continued. “He didn’t want to have to worry about the mortgage being foreclosed or holes in the ceiling where rain came in, or a limited wardrobe. He wanted a job and wanted to be able to earn enough to own his own home.” His parents sent him religious schools in Brooklyn, in Pennsylvania, in Italy, then a rabbinical college in Brooklyn. “Joseph had difficulty buying into ‘the program,’” so he turned to real estate.

Dow’s memo describes Levitin as “an outlier who was anxious to live and succeed in a go-go secular world his parents and siblings never chose to inhabit. Joseph learned well from his mentors” in crime. The memo proceeds to magnify the role of lawyers whom Levitin recruited to the conspiracy, while portraying Levitin’s most significant act the help he eventually offered the prosecution. In Dow’s telling, Levitin “did not appreciate how far he has strayed from the religious precepts by which his family lives. He has returned to those roots. He has become a successful businessman.”

Double-Dealing

The lead prosecutor, Assistant U.S. Attorney David Huang, confirmed to Judge Hall that Levitin played a crucial role in gaining convictions in this conspiracy. In remarks in court and in the government’s sentencing memo, on the other hand, Huang continued to describe Levitin as “one of the three most culpable” ringleaders in the scene.

The government’s memo contains details of Levitin’s actions that Dow left out — including his turning on his co-conspirators even before he stopped committing crimes with them and participating with the government.

Defense attorney Dow recognized that he couldn’t appear to downplay Levitin’s role too much: He had sat in on Hall’s Dec. 16 sentencing of another leader of the conspiracy and heard Hall dismiss defense attempts to pin blame on irresponsible banks or lawyers. Dow Friday quoted back to her a remark she had made that day from the bench: “There were many people on the road traveling 85 miles per hour. Only one got pulled over. It didn’t make that person any less guilty.”

At the same time, to try to convince Hall to give Levitin as little jail time as some of the smaller players, Dow sought to portray Levitin’s older, more experienced fellow leaders of the conspiracy as more culpable — because of their age and experience. He sought to portray the lawyers involved as perhaps as culpable as Levitin, even though they may have earned hardly any money and handled only a small batch of closings apiece. He called laywers the “bishops” in real-estate deals. They “bless the proceedings.”

Hall wasn’t buying. Levitin may have been 21 when he entered the conspiracy, she said. But he was already a successful businessman. He learned fast how to fake real-estate deals and pocket illicit cash. “A lie” is the same if uttered by a 21-year-old or a 51-year-old, she said.

As for the lawyers — “If I had a lawyer who did 46 closings over two years, I don’t think they would have gotten [only] 24 months in jail.” Levitin oversaw the fradulent theft of $7 million, she said. “Seven million dollars is a lot of money.”

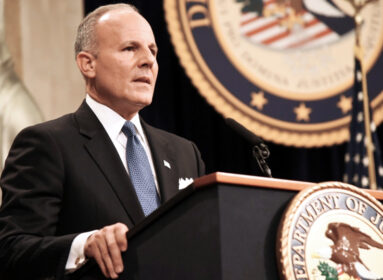

CAP: Levitin, at right, with attorney Dow outside court.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger