By Shlomo Riskin

We recently marked one year since the passing of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, the great halachic and political leader of millions of Jews throughout Israel and the world. Our portion this week devotes an entire chapter to the purchase of a gravesite for the burial of Sarah, Matriarch of Israel. What is the meaning behind Abraham’s bargaining for a burial plot, and what connection, if anything, does this biblical story have to do with Rabbi Ovadia’s funeral last year?

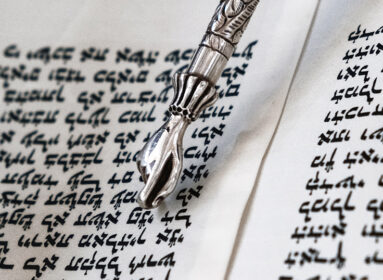

Let us begin with our text. Abraham, an itinerant shepherd throughout the area that will one day become the Land of Israel, approaches the “Children of Heth” (the Hittites): “I am a stranger-resident among you,” he says. “Give me possession of a gravesite so that I may bury my dead from before me” (Gen. 23:4).

The Children of Heth seem more than generous in their response: “You are a Prince of God in our midst; in the choicest of gravesites may you bury your dead. None of us will withhold his gravesite from you” (23:6).

Abraham is not satisfied. He requests a meeting with Ephron the son of Zohar, to whom he wishes to pay “top dollar and cash-in-hand” for the Machpela Tomb at the end of his field. The residents of Heth want to give Abraham a free burial plot; Abraham insists on paying a high price.

The “bargaining” begins.

Ephron insists on giving the patriarch a free plot; but when he finally names a price, it is an excessive 400 silver shekels. According to the Code of Hammurabi, an average workingman’s annual wages at the time were six to eight shekels. Abraham paid the equivalent of 70 years of wages for one burial plot.

What is the text teaching us? Abraham is heaven-bent on establishing the unique Hebrew identity of his beloved wife, Sarah, no matter what the financial cost – an identity which will be defined and determined by her gravesite. In the ancient world, a citizen of a specific locality received only one advantage as a result of his citizenship: a free burial plot in that locality (with the exception of Athens, where citizens had the right to vote).

Now we can understand Abraham’s bargaining with the children of Heth. Abraham opens the conversation defining himself as an alien resident; on the one hand, he is a Hebrew, not a Hittite, a stranger of a radically different religion and culture; on the other hand, he is an upright resident, ready to cooperate with the Hittite civil laws in every way. The children of Heth are happy to adopt this highly successful patriarch of a new tribe as one of their own, to “assimilate” him within their culture.

Abraham is ultimately willing to pay any price for Sarah’s total independence from their surrounding civilization, for her persona as a Hebrew will be expressed and established by the place and manner in which she is buried. Where you are buried and how you are mourned reveals volumes about the life that you lived. The manner in which a nation reveres its dead goes a long way in defining its future. Is it any wonder that the Hebrew word kever (burial plot) is used by the talmudic authorities as a synonym for rehem (womb)?

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef’s funeral last year was undoubtedly the largest in Israel’s history, estimated to have included some 800,000 mourners. It expressed the amazing power of Torah, the most authentic and eternal legacy of our people. He was mourned as a Prince of Torah, as the greatest unifying authority of Torah law in our generation, a unifying Torah respected and accepted by Ashkenazim, Sephardim, haredim (ultra-Orthodox), Modern Orthodox and secular alike – for representatives from all walks of Israeli life came to his door to seek halachic advice and live by his rulings.

His Torah, true to the tradition of the greatest Torah leaders of the last 2,000 years, was unique in our generation. It was a Torah which breathed democracy, because although he came from Iraq and expressed the Iraqi (Babylonian) tradition, his was the ultimate word for Ashkenazim, too – and so he gave standing and respect to a population which had previously been discriminated against by the ruling WASP (“White Ashkenazi Sabra Populace”) of Israel.

His Torah was a Torah of peace and moderation – he ruled that in the interest of peace and the saving of human lives, we could give up Yamit in Sinai. His Torah was a Torah of inclusiveness – he ruled that the Jews of Ethiopia, considered to be of the lost tribe of Dan by the 16th century authority Radbaz (Rabbi David ben Zimra), were legitimately Jewish and did not require conversion, and he ruled that all the military conversions were legitimate. And his Torah was a Torah of compassion, which sought to solve problems rather than create them.

May his memory and his way serve as a light that will continue to illuminate the future of our people.

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin is chancellor of Ohr Torah Stone and chief rabbi of Efrat, Israel.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger