By Shlomo Riskin

“This shall be the law of the leper in the day of his cleansing, he shall be brought unto the priest” (Lev. 14:2).

Do houses have souls? Do nations?

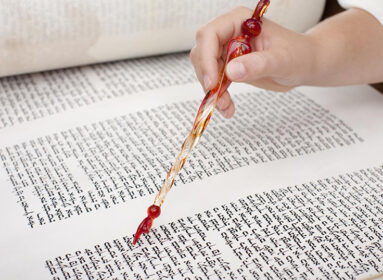

In the opening of this week’s portion of Metzorah, the Torah introduces us to the law commanding a person to go to the priest who determined the nature of his ‘plague of leprosy’ (nega tzara’at). If the scab was diagnosed as qualifying, the development of the disease required the constant inspection of the priest. Our portion of Metzorah opens with the complex details of the purification process once the disease is over. This ritual requires two kosher birds, a piece of cedar, crimson wool, and a hyssop branch. One bird is slaughtered while the other is ultimately sent away. But this is only the beginning of a purification process that lasts eight days, culminating in a guilt offering brought at the Holy Temple.

Only after the entire procedure was concluded could a person be declared ritually clean. But if this all sounds foreign, complicated and involved, the Biblical concepts appear even stranger when we discover that this “plague of leprosy” is not limited to humans: “God spoke unto Moses and Aaron, saying: ‘When you come to the land of Canaan, which I give to you as an inheritance, and I put the plague of leprosy in a house of the land of your possession, then he that owns the house shall come and tell the priest” (Lev. 14:33-35).

How are we to understand that the very same maladynega tzara’at – that describes what is generally referred to as a leprous ailment of a human being, has the power to also afflict the walls of a house – a person is one thing, but a house suffering a plague of leprosy?

When we examine the text we find an interesting distinction between these two species of tzara’at. “The plague of leprosy” that strikes people is presented in straight-forward terms: “If a person shall have in the skin a swelling, a scab, or a bright spot, and it be in the skin of his flesh the plague of leprosy” (Lev. 13:3).

But the plague that strikes houses is introduced by an entirely different concept: “When you come to the land of Canaan, which I am giving to you as an inheritance, I will put the plague of leprosy” (Lev. 14:34).

Why is the commandment of the plagued house placed in the context of the Land of Israel? If indeed the disease can descend upon houses, why only the houses in the Land of Israel?

A third element to consider are the differences in the visible aspects of these two diseases. Regarding the person himself, the Torah speaks of a white discoloration, but as far as the house is concerned, if a white spot appeared on the wall nothing would be wrong.

“Then the priest shall command that they empty the house… and he shall look at the plague and behold, if the plague be in the walls and consists of penetrating streaks that are bright green or bright red…” (Lev. 14:36-37).

We must keep in mind that the translation a “plague of leprosy” is inadequate. Biblical commentaries ranging from the 12th century Ramban to the 19th century Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch claim that nega tzara’at cannot possibly be an illness in the classic sense, for if that were true, why does the Torah assign the ‘medical’ task of determining illness to a priest? Priests were teachers and keepers of the religious tradition, not doctors or medical experts.

If nega tzara’at is a spiritual illness, a metaphor for the state of the soul, then just as one soul is linked to one body, the souls of the members of a family are linked to the dwelling where they all live together. And the walls of a house certainly reflect the atmosphere engendered by its residents. A house can be either warm or cold, loving or tense. Some houses are ablaze with life, permeating Jewishness and hospitality: mezuzot on the doorposts, candelabra, menorahs and Jewish art on the walls, books on Judaism on the shelves, and place-settings for guests always adorning the table. But in other homes, the silence is so heavy it feels like a living tomb, or the screams of passionate red-hot anger which can be heard outside frighten away any would-be visitor, or the green envy of the residents evident in the gossip they constantly speak causes any guest to feel uncomfortable.

Why should this “disease” be specifically connected to the Land – or more specifically, the people – of Israel? To find the unique quality of Israel all we have to do is examine the idea of Beit Yisrael, the House of Israel. The nature of a household is that as long as there is mutual love and shared responsibility, then that house will be blessed and its walls won’t be struck with a plague of leprosy. To the extent that the covenant of mutual responsibility is embraced by the people, then the house of Israel will be blessed. We must act toward each other with the same morality, ethics and love present in every blessed family. If not, a nega tzara’at awaits us. And our holy land of Israel is especially sensitive to any moral infraction.

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin is chancellor of Ohr Torah Stone and chief rabbi of Efrat, Israel.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger