What happened to all the art that Nazis looted?

This Jewish Museum exhibit tells the story of several masterworks

By Chloe Sarib

Great works of art often become so present in our everyday lives — the “Mona Lisa” on a mug, “The Starry Night” on a sweater, Basquiat in Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s Tiffany campaign — that it’s easy to forget how fragile the originals are. These images that populate our collective conscious-ness all started as a single destructible canvas. But most museums don’t highlight the life these artworks have had as physical objects — often be-cause that history is wrapped up in colonialism and theft.

At the new Jewish Museum exhibition “Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art,” which opened last month in New York, this over-looked aspect of a painting’s history becomes the focus.

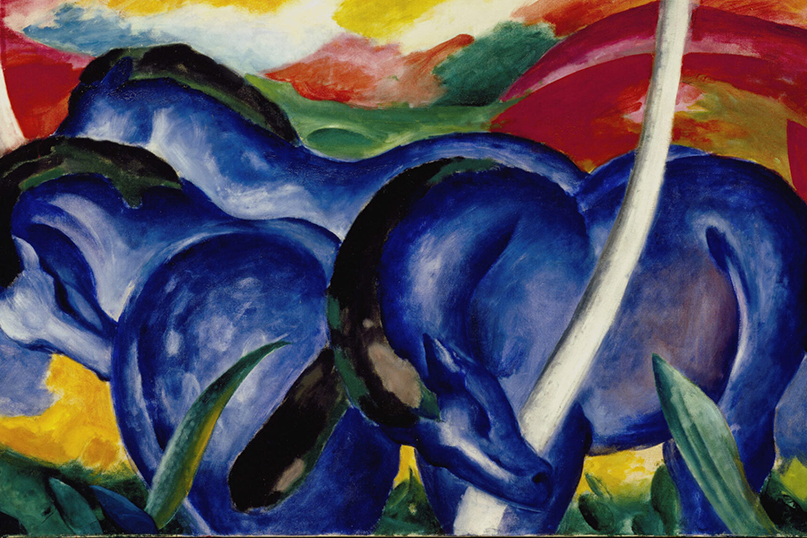

“It is often difficult to understand the ‘biography’ of an artwork simply by looking at it, and even more difficult to uncover the lives and experiences of the people behind it,” reads the text on the first wall visitors encounter, displayed beside Franz Marc’s “The Large Blue Horses.”

The gallery is organized around how the artwork it features — including works by Chagall and Pissarro (both Jewish), Matisse, Picasso, Bonnard, Klee and more — came to hang there. All the pieces displayed have one quality in common: They were either directly affected or inspired by the looting and destruction of the Nazis.

“The vast and systemic pillaging of artworks during World War II, and the eventual rescue and return of many, is one of the most dramatic stories of twentieth-century art… Artworks that withstood the immense tragedy of the war survived against extraordinary odds,” the text continues. “Many exist today as a result of great personal risk and ingenuity.”

One of the most striking instances of bravery the exhibit recounts is that of Rose Valland, a curator at the Jeu de Paume, which housed the work of the Impressionists. During the collaborationist Vichy regime, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or ERR, took over the museum build-ing. The ERR, “one of the largest Nazi art-looting task forces operating throughout occupied Europe,” used the space to store masterpieces it had taken.

Valland, who had worked at the Jeu de Paume before the war, stayed on during the Occupation and collaborated with the French Resistance to track what the Nazis did with the stolen paintings.

“At great personal risk,” including sneaking into the Nazi office at night to photograph important documents, “she recorded incoming and outgoing shipments and made detailed maps of the extensive network of Nazi transportation and storage facilities.” Pieces by Jewish or modernist art-ists were often labeled “degenerate” and slated for destruction. Valland was unable to save many of them and referred to the room where they were housed as the “Room of the Martyrs.”

In the exhibit, Valland’s story is overlaid on a 1942 photograph of this room. Some of the works in it — by Andre Dérain and Claude Monet, among others — are believed to have been destroyed. But three of the paintings that survived are on the adjacent wall: “Bather and Rocks” by Paul Cezanne, “Group of Characters” by Pablo Picasso, and “Composi-tion” by Fédor Löwenstein. They last hung together in the Room of the Martyrs, awaiting their fate like many of the Jews of Europe.

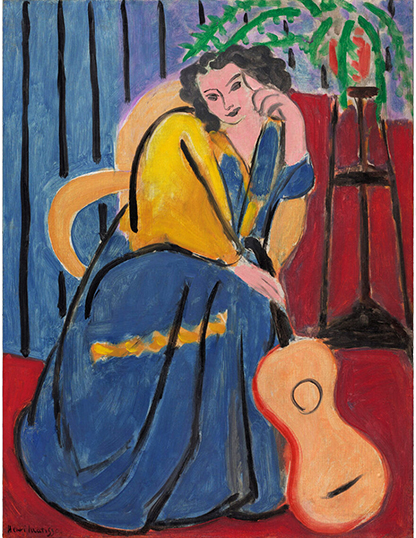

Some Impressionist paintings on display at the Jewish Museum, like Ma-tisse’s “Girl in Yellow and Blue with Guitar,” spent the Holocaust in the personal collections of high-ranking Nazi officials — Hermann Goering in this case.

Others — like Marc Chagall’s “Purim,” a study for a commissioned St. Petersburg mural he never painted — were confiscated, labeled “degenera-te” for their Jewish authors and content. But that didn’t stop the Nazis from selling them to fund the war effort. The exhibit calls out these finan-cial incentives that spurred the Nazis to steal from Jewish collectors: It was as much about seizing Jewish wealth as about any ideological be-liefs. Germany was in debt when the Nazis came to power, and even “de-generate” art was often sold on the international market “to raise funds for the Nazi war machine” if they thought it would fetch a good price. So, the Nazis weren’t even principled in their anti-Jewishness; they were happy to profit off of works by Jewish artists and were often motivated by simple greed.

“Purim,” painted in 1916-17, contains “folkloric imagery and vivid colors drawn from Chagall’s memories of his childhood in a Jewish enclave in the Russian empire.” Seeing a depiction of a holiday that celebrates Jews surviving persecution in this World War II context is poignant.

The exhibit includes documents from the collection points, in Munich and Offenbach, where the Allies traced the paths of stolen work, stored them when recovered, and eventually tried to “reverse the flow” by sending them back where they belonged. Staring at a map of how far some con-fiscated Jewish literature had traveled is intimidating in the sheer scope of this staggering pre-internet task.

“Afterlives” also features art by Jews who faced persecution directly — pieces made at the camps themselves or while in hiding. The haunting, delicate drawings of Jacob Barosin, who made them while fleeing to France and ultimately to the U.S., were moving. And the presence of “Bat-tle on a Bridge,” a looted painting so revered by the Nazis that Hitler had earmarked it for his future personal Fuhrermuseum in Austria, was chilling. Its inventory number, 2207, is still visible on the back of the can-vas.

But what is most captivating about the exhibit was how it helps the visitor imagine what Jewish cultural life was like before the Nazis came to power. I often have the impression that accounts of the Holocaust concentrate more on the horrors of the camps and less and on the individual lives and communities they destroyed. Here, I learned about Jewish gallerist Paul Rosenberg, whose impressive gallery the Nazis co-opted — after seizing his valuable art, of course — for the “Institute of the Study on the Jewish Question,” an antisemitic propaganda machine. I learned about his son Alexander, who, while liberating a train with the Free French Forces thought to be full of passengers, recovered some of his father’s art against all odds. I saw August Sander’s “Persecuted Jews” portrait series from late-’30s Germany, and looked into the faces of people forced to leave their homes. And I saw a huge collection of orphaned Judaica and ritual objects from Danzig (now Gdansk), Poland, where the Jewish com-munity shipped two tons of their treasures to New York for safekeeping in 1939. If no safe free Jews remained in Danzig 15 years later, these items would be entrusted to the museum. None did.

The exhibit also includes the work of four contemporary artists grappling with the contents of “Afterlives” and the era it evokes. Maria Eichhorn pulls from the art restitution work of Hannah Arendt. Hadar Gad uses her painstaking process to paint the disassembly of Danzig’s Great Syna-gogue. Lisa Oppenheim collages the only existing archival photograph of a lost still-life painting with Google Maps images of the clouds above the house where its Jewish owners lived. And Dor Guez, a Palestinian North African artist from Israel, created an installation from objects belonging to his paternal grandparents, who escaped concentration camps in Nazi-occupied Tunisia. They previously ran a theater company, and a manu-script written by his grandfather in his Tunisian Judeo-Arabic dialect was damaged in transit. Guez blew up the unfamiliar handwriting and ink blots into abstracted prints that hang on the wall. In Guez’s words, “the words are engulfed in abstract spots, and these become a metaphor for the harmonious conjunction between two Semitic languages, between one mother tongue and another, and between homeland and a new country.”

I’ll let the exhibit’s curators sum up how I felt as I left: “Many of the artists, collectors, and descendants who owned these items are gone, and as the war recedes in time it can become even harder to grasp the traumatic events they endured. Yet through these works, and the histories that at-tend them, new connections to the past can be forged.”

“Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art” is on view at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan through Jan. 9, 2022.

Chloe Sarbib is associate editor of arts and culture at Alma, where this ar-ticle originally appeared.

Worcester Art Museum showcases art stolen from prolific Viennese collector during World War II

By Stacey Dresner

WORCESTER, Massachusetts – Several pieces of art looted by the Nazis during World War II are now on display in an exhibit at the Worcester Art Museum.

“What the Nazis Stole from Richard Neumann (and the search to get it back)” arrived in Central Massachusetts in April; the exhibit will be on display until Jan. 16, 2022.

Richard Neumann was an Austrian-Jew, born in Vienna to a wealthy family that owned textile mills throughout the country. He received his PhD in Philosophy from the University of Heidelberg but went on to serve as the president of his family’s textile business.

He was a lover of art, who by his 40s had collected more than 200 works, mostly Baroque art of the early 1700s. He lost much of that art after the Nazis occupied Austria, through forced sales and an inability to get export licenses. Neumann and his wife escaped from Nazi-occupied Vienna in 1938 and was able to send some of his art ahead of him to Paris. Forced to flee again in 1942, he sold what was left of his collection – for below market prices — and booked passage on a boat to Cuba. The Neumanns lived for several years in Cuba where Richard worked in the textile mill industry. He moved to New York in the 1950s.

While he attempted lawsuits to have his art returned to him, none of his efforts were successful. Neumann died in 1959.

For more than 50 years, members of his family have tried to reassemble his art collection. Two of the pieces on display at the Worcester Art Museum, “Monks at Mealtime” by Alessandro Magnasco (1667-1749) and Neri di Bicci’s ‘Madonna With Child’ (mid-1400s) were put up for sale at Sothby’s in recent years and were reacquired by Neumann’s family.

In all, 14 pieces of art that have been returned to Neumann’s descendants make up the exhibit at the Worcester Art Museum. They include 13 Old Master paintings and sculptures, including works by artists of the Italian Renaissance including Alessandro Magnasco, Giovanni Battista Pittoni, Alessandro Longhi, Alessandro Algardi and Giuseppe Sanmartino.

oil on panel.(Courtesy the Selldorff Family)

The exhibit also documents his escape from Vienna and Paris during the war, his passion for art, and the family’s 50-year effort to reassemble his collection.

The Jewish Federation of Central Mass. is a major sponsor of the Richard Neumann exhibit. The Federation sponsored a Zoom lecture on the Richard Neumann and his art last spring.

“I look at it through the lens of Holocaust remembrance and the lessons that are associated with that,” said Steven Schimmel, executive director of the Jewish Federation of Central Mass.

“What I’m impressed by about the exhibit itself is that it helps to tell the story of the Holocaust in a personal way,” Schimmel continued. “It provides insight into the fact that the victims of the Holocaust were not only real people, but in some cases, very prominent leaders in their communities. The story of the Neumanns is told through this art which helps to bring a light and personality to Holocaust remembrance.

“I think anything that can be done to help tell the story of those who were affected by the rise of Naziism and the terrors of that time is important, but when you are able to do it in a creative way like this, there is something more visceral about it.”

As part of its sponsorship, Federation members will be able to visit the exhibit free of charge in the month of October.

Also providing support for the exhibit is the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University.

“The tragedy of the Holocaust is so vast and complicated, and the restitution of these artworks may not seem like the most compelling aspect from the tragic angle, in the context of all the last lives, but I think it’s still very important to understand that a major part of the Nazi project had an economic dimension, a cultural dimension,” explained Mary Jane Rein, executive director of the Strassler Center. “Taking these artworks and basically forcing Jewish collectors to sell them, or to leave them behind, is a very important aspect of the economic dimension of the Holocaust and I think that it demands our attention. The fact that so much material still remains in museums is deeply shameful. While it may not be tragic in terms relative to the massive loss of life that the Jewish community experienced during the Holocaust, it’s still something that is a part of the Nazi project that deserves our attention and really deserves our outrage. And I think that museums that hold on to these materials should be really ashamed of it. So, I’m very proud of the fact that the Strasser center is partnering with the Worcester Art Museum and bringing attention to this subject… I hope that the museum is successful in showing the public the importance of this effort to bring artwork back to its rightful owners.”

For more information, email information@worcesterart.org or call (508) 799-4406.

Main Photo: The Room of the Martyrs, in the Archives du Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangère – La Courneuve (Jewish Museum)

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger