By Ben Harris

(JTA) – As the coronavirus pandemic forces Jews around the world to contemplate a Passover holiday in which large family gatherings will be all but impossible, an unusual question posed to a group of Israeli rabbis led to an extraordinary answer.

The question was whether it might be permissible for families to use internet-enabled videoconferencing to celebrate the Passover seder together even as they are sequestered in separate homes. Orthodox Jewish practice normally prohibits the use of electronics on the Sabbath and Jewish festivals, but might the unprecedented restrictions suddenly thrust upon billions of people permit an exception?

Remarkably, 14 Sephardic rabbis last week answered in the affirmative.

Some conditions were attached. The computer would have to be enabled prior to the onset of Passover and remain untouched for the duration of the holiday. And the leniency would only apply to the current emergency.

But given the unique importance of the seder ritual and the extreme conditions now in effect, the rabbis wrote, the use of videoconferencing technology is permitted “to remove sadness from adults and the elderly, to give them the motivation to continue to fight for their lives, and to avoid depression and mental weakness which could bring them to despair of life.”

The coronavirus pandemic has upended so many parts of life that it’s perhaps little surprise that it’s also having a significant impact in the field of Jewish law, or halacha. The sudden impossibility of once routine facets of observant Jewish life has generated a surge in questions never considered before – and modern technology means that Jews the world over are more able than ever to ask those questions and share their answers.

“I don’t think there’s ever been anything like this because of the proliferation of questions and because of the extraordinary means of communications,” said David Berger, a historian and dean of the Graduate School of Jewish Studies at Yeshiva University.

Among the questions rabbis have had to confront during the corona crisis: Is it permissible to constitute a Jewish prayer quorum over internet-enabled videoconference? Can married couples be physically intimate if the woman cannot immerse in a ritual bath because they are closed for public health reasons? How should burials be handled if authorities prohibit Jewish rituals around the preparation of bodies? Can synagogue services be live-streamed on Shabbat?

Rabbis are also beginning to consider some agonizing possibilities. Several Conservative movement authorities have published papers about what Jewish ethics has to say about medical triage, anticipating a moment when doctors may have to make difficult choices about who gets treatment. (See story on adjacent page)

“This has been ‘yomam valaylah’ – it’s been day and night,” said Rabbi Elliott Dorff, the co-chair of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, the Conservative movement’s authority on questions of Jewish law. “Once this is all over, this is going to be a really interesting case study of how halacha evolves quickly when it needs to.”

In Romania, the government’s recent declaration that any coronavirus fatalities had to be buried immediately presented Chief Rabbi Rafael Shaffer with a tortuous dilemma: What if a Jewish person died on Shabbat? Burying the body immediately would have resulted in a clear violation of the Jewish Sabbath, but allowing the body to be cremated is also a severe violation of Jewish law.

“The burial should be done on Shabbat if necessary,” Shaffer told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency after consulting with rabbinic authorities in Israel. “If it’s the only possibility to avoid cremation, then it should be done on Shabbat by non-Jews.”

For the moment, that situation remains in the realm of the theoretical. But other halachic questions are of urgent necessity. Many of the recent opinions have explicitly invoked the principle of “she’at had’chak” – literally “time of pressure,” a concept in Jewish law that permits a reliance on less authoritative opinions in emergency situations.

“No one thinks you can permit biblical violations for a pressure that doesn’t amount to threatening lives,” said Rabbi Aryeh Klapper, the Orthodox dean of the Center for Modern Torah Scholarship. “But maybe you can rely on less authoritative understandings of what the biblical prohibition is.”

The Conservative movement, which tends to take a more flexible line on matters of Jewish law than Orthodox authorities, has supported a number of leniencies under the rubric of she’at had’chak.

In March, Dorff and his law committee co-chair, Rabbi Pamela Barmash, issued an opinion permitting a prayer quorum to be constituted over internet-enabled videoconference. That opinion, which temporarily suspended a nearly unanimous 2001 ruling that such a quorum was not permissible, would enable the recitation of the Mourner’s Kaddish by people isolated in their homes. Common practice is that the mourner’s prayer can only be said if 10 Jewish adults are gathered in one physical location.

The law committee also has expressed support for loosening various restrictions around physical touch between married couples should Jewish ritual baths be forced to close. Couples that closely observe Jewish law traditionally refrain from any form of touch for the period of the woman’s menstruation and for a week after, resuming contact only after immersion in a mikvah.

But the committee posted a letter on its website this week from Rabbi Joshua Heller asserting that under certain circumstances, and only for the period of the coronavirus crisis, a woman could resume sexual relations with her husband after showering in 11.25 gallons of water – a rough approximation of the Talmudic measure of 40 kabim.

“I think we are learning from earlier historical epochs of crisis and taking inspiration from the flexibility that our predecessors showed,” said Rabbi Daniel Nevins, a committee member and the dean of the rabbinical school at the Jewish Theological Seminary.

To be sure, not all rabbis have accepted these leniencies.

After Rabbi Daniel Sperber, a liberal Orthodox rabbi in Israel, issued an opinion permitting some forms of physical touch between married couples should ritual baths become inaccessible, another Israeli Orthodox rabbi, Shmuel Eliyahu, called the opinion a “complete mistake.”

Israel’s two chief rabbis, David Lau and Yitzhak Yosef, said the opinion permitting videoconferencing at the seder was “unqualified.”

And Rabbi Hershel Schachter, a leading Orthodox authority at Yeshiva University, wrote recently that a prayer quorum could not be constituted by participants standing on nearby porches – even if they could all see each other.

“The 10 men must all be standing in the same room,” Schachter wrote.

But Schachter, who has personally published no less than a dozen opinions on matters related to coronavirus, has shown flexibility in other areas.

Schachter has ruled that a patient discharged from a hospital on Shabbat can be driven home by a family member because it’s dangerous to remain in the hospital longer than necessary and taxis carry their own risks of coronavirus transmission. He has said that isolated individuals who suffer from psychological conditions that might endanger their lives if they were unable to communicate with family may use phone or internet to communicate on a Jewish holiday.

And in a ruling that has wide applicability at a time when many people are preparing to host Passover meals for the first time, he suggested a workaround for the obligation of immersing utensils in a ritual bath before using them. Since baths are now closed for such purposes, Schachter ruled that one could use the utensils without immersion by first declaring them legally ownerless – a workaround that would normally not be permitted.

Many rabbis have expressed concern that such loosening of the rules, even if expressly done only to address a pressing (and presumably temporary) need, might nevertheless create new norms of behavior that will outlast the current crisis. If so, it wouldn’t be the first time.

According to a recent article by Rabbi Elli Fisher, during the 19th-century cholera epidemic, there were so many mourners that Rabbi Akiva Eger, who led the Jewish community in Poznan, Poland, ruled that it was permissible for many mourners to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish simultaneously. At the time, the practice was that only one person recited Kaddish at a time.

Given the numbers of the dead, that practice would have left people with few opportunities to recite the mourner’s prayer. The practice of reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish as a group remains the dominant one in synagogues today.

“I do think that our people are wise enough and insightful enough to understand the difference between this crisis situation and normal situations,” Barmash said. “I think in some sense that fear is giving in to a low opinion of our people. And I think that our people are wise and insightful and do recognize the distinction.”

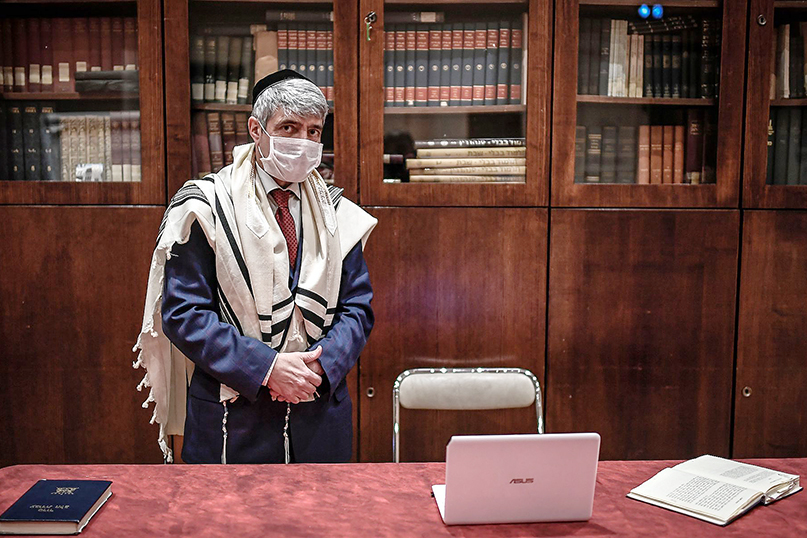

Main Photo: French Rabbi Philippe Haddad prepares for a Shabbat service via videoconference at the Copernic Synagogue in Paris, March 28, 2020. (Credit: Stephane de Sakutin/AFP via Getty Images)

What happens when we run out of ventilators? Jewish law and state guidelines may have different answers.

By Ira Bedzow

NEW YORK, New York – The COVID-19 pandemic facing this city will test our country’s most deeply cherished values: respect for multiculturalism and religious freedom on the one side and the state’s responsibility to promote the common good on the other. This inherent tension is quite literally an issue of life and death.

As the Ledger went to press, it appeared that the tide was beginning to turn in New York City, but hospitals still remained close to experiencing a shortage of personal protective equipment and ventilators, which would greatly tax the hospital system’s ability to provide care. To be clear, at press time, the city’s hospitals had not run out of ventilators. But preparation was warranted in New York as well as elsewhere around the country where the virus had not yet peaked..

As hospitals develop triage protocols to prepare themselves for the time when they will need to treat too many patients with not enough medical resources, rabbis and public religious figures are grappling with the halachic answers to those same questions. And the protocols that many hospitals may ultimately adopt are going to clash with the position held by most, if not all, Orthodox rabbinic authorities.

If two patients show up at the hospital at the same time in need of the only ventilator, both hospital guidelines and rabbis assert that physicians should use clinical judgment to determine which patient has a better chance of survival.

The problem arises once a patient is already put on a ventilator. In New York, for example, many hospitals look to the 2015 Ventilator Allocation Guidelines, written by the New York State Task Force on Life and the Law, to help them figure out how to ration ventilators.

In a crisis, hospitals continually assess patients to determine whether they should stay on a ventilator or should be removed so that someone else can have a chance to live. The 2015 guidelines recommend that after being placed on a ventilator, patients must be reassessed after 120 hours, and every 48 hours thereafter, to see if there has been an improvement in their overall health. If there hasn’t been, the patient should be removed from the ventilator so it can be given to another person with a better chance of survival.

The details of the guidelines’ recommendations would not apply in the case of COVID-19, since patients typically must be on ventilators for a week or two before they show signs of improvement. Therefore, any new guidelines that emerge will necessarily have longer timelines before recommending reassessment. But the overall idea of periodically seeing if a patient should continue on a ventilator or be removed for the sake of saving another person will be adopted in the new guidelines.

The normative Orthodox position in such a situation is far different: Once placed on a ventilator, a patient cannot be taken off unless the condition improves or the patient passes away – even if someone else with a higher chance of survival will be deprived of a ventilator as a result.

This position is grounded in the idea that “one life should not be pushed aside for another.” In the Mishneh Torah, Maimonides writes that in a situation where a group of Jewish people is being accosted by idolaters who threaten them by saying, “Give us one of you and we will kill him. If you don’t, we will kill all of you,” they should all be killed rather than hand over a Jewish life. In essence, halachically, it is better to allow many to die than to actively participate in killing a single person.

The majority of contemporary American Orthodox rabbis rely on the rulings of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein to provide practical guidance in the case of triage. When Feinstein was asked about triage in the early 1980s, he wrote (Igrot Moshe, Hoshen Mishpat 2:73-75) that if a patient is already being treated, even if physicians incorrectly judged his or her survivability and mistakenly allocated resources to his care, another person with higher chances of survival does not take precedence and resources should not be reallocated.

Feinstein’s reasoning is as follows: There is no obligation for one patient to surrender his life for the sake of another. Therefore, when the patient was allocated medical resources, the resources in effect became the patient’s for as long as the individual maintained life. It is not the case that medical resources are given to the patient contingently by the hospital until the hospital decides to take them away for the sake of another person. Rather, the resources have been committed to the patient as long as they are keeping him alive, without contingency. This is the case even if the second person is in a life-threatening condition and could be saved if given the resources.

As you can see, the difference is clear – hospitals will re-evaluate and reallocate resources in hopes of maximizing the number of people they can save. The Orthodox position places a primary value on stopping any type of active killing. The religious mandate is to endeavor to save lives, not to think that we have ultimate power to decide who lives and who doesn’t.

As New York City hospitals have not yet reached capacity, this clash of values has stayed in the realm of the theoretical. However, we already are beginning to see how even the idea that hospitals will not follow Jewish law is causing great worry in the Jewish community.

Maimonides Medical Center, located in the heavily Jewish Borough Park section of Brooklyn, is following the concerns of the Orthodox community: The hospital has committed to intubate patients and work with local religious leaders to provide patients the care they need based on their religious beliefs for as long as they can. However, Gov. Andrew Cuomo has pushed to have all of the city’s hospitals work as one system, which will include a set of common guidelines when there may not be enough medical resources to go around.

If, God forbid, we get to a point where triage protocols must be followed, the state will choose the common good over respect for religious freedom. This calculation is embedded in the Western concept of liberty from the outset, as expressed by John Stuart Mill in his essay “On Liberty.”

“The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others,” Mill wrote.

Though this may not be the first case where the state is faced with choosing the common good over the rights of individuals, it certainly is the most devastating. It’s tragic not only because hospitals may not have enough resources to care for its patient population, but also because our country must push aside the values of tolerance and religious freedom for another set of priorities.

Ira Bedzow is the director of the Biomedical Ethics and Humanities Program at New York Medical College.

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger