The new normal: Families on Zoom, solo seders and broken traditions

By Ben Sales

(JTA) – Rena Munster was looking forward to hosting a Passover seder for the first time.

In past years, her parents or another relative hosted the meal. But this year she had invited her parents, siblings and other extended family to her Washington, D.C., home. Her husband, an amateur ceramics artist, was making a set of dishes for the holiday.

And she was most excited for her family’s traditional day of cooking before the seder: making short-rib tzimmes, desserts that would pass muster year-round, and a series of harosets made by her uncle and tailored to each family member’s dietary restrictions.

Then came the new coronavirus. Now the family is preparing to scrap travel plans and hold the seder via video chat, like so much else in this new era. Munster expects to en-joy her family’s usual spirited discussions and singing. But she will miss the meal.

“The hardest thing to translate into an online platform is going to be the food,” she said. “The family recipes and all the things that we’re used to probably won’t be possible. … We always get together to help with the preparations, and that’s just as much a part of the holiday as the holiday itself.”

In a Jewish calendar packed with ritual observances and religious feasts, the Passover seder is the quintessential shared holiday experience. It is perhaps the most widely observed Jewish holiday ritual in the United States, according to the Pew Research Center’s 2013 study of American Jewry. And the story of the journey from slavery to freedom, along with the songs, customs and food, have become a core part of Jewish tradition.

But all of that has been upended by COVID-19 and the restrictions necessary to contain its spread. Israel has limited gatherings to 10 people – smaller than many ex-tended families – and Americans have been asked to do the same. Countries are shutting their borders, making Passover travel near impossible. Hotels and summer camps that have held Passover programs, as well as synagogues that hold communal seders, have been canceled.

Kosher food professionals say shelves of kosher grocery stores will probably still be stocked with matzah and other Passover staples. Rabbi Menachem Genack, CEO of the Orthodox Union’s Kosher Division, said that due to social distancing, some kosher supervisors have been supervising food production plants via a live-streamed walk-through. But he said the food is still being produced.

“Most of the kosher-for-Pesach production began a long time ago,” he said. “There’s not going to be any problem at all in terms of availability of products for Pesach.”

On the other end of the supply chain, Alfredo Guzman, a manager at Kosher Market-place in Manhattan, said two deliveries of Passover food have been delayed but were expected to arrive momentarily. Guzman was worried as well that because of social distancing measures, he would only be allowed to let in a limited number of customers at a time during one of the busiest times of the year.

“I really don’t know what we’re going to have, what is coming, what is not coming, regarding products for Passover,” he said. “A lot of people are going to get nervous.”

Even if the food does make it to the shelves and into people’s kitchens, the limitations on large gatherings could be a problem for people like Alexander Rapaport, who runs the Masbia network of soup kitchens in New York City. Masbia hosts two seders every year for the needy, usually drawing around 40 people per night. Rapaport stressed that because many observant Jews having little trouble finding an invitation to a family or communal seder, those who come to a Masbia seder truly have nowhere else to go.

“We are hoping for the best and we will definitely follow the Health Department guide-lines on how to operate a seder – spread out the seating, limit capacity,” he said on March 17. “It depends how severe it will be three weeks from now. I hope we don’t have to cancel.”

As Passover nears amid the coronavirus outbreak, some Jews would find any kosher grocery store a luxury. Rabbi Ariel Fisher, who is living in Dakar, Senegal, for the year while his wife conducts field research for her doctorate in anthropology, hopes to re-turn to New York City to officiate at a wedding and spend the holiday with his parents. But if travel becomes impossible, he may be stuck in the West African city, where he estimates that the nearest kosher store is more than 1,000 miles away in Morocco.

Now he is scrambling to make sure that they will have enough matzah and kosher wine for the holiday. He is hoping the local Israeli diplomats will be able to get a shipment of matzah, and also asked a good friend in the local U.S. embassy – which has access to Amazon Prime – to order some for him online. Barring that, he will try to import matzah all the way from South Africa.

And if all of that fails, he plans to make matzah himself – starting with the actual wheat. In any case, if Fisher and his wife end up in Senegal for the holiday, they plan to host a seder for the tiny community of Jews there who also would be unable to travel.

“If we are actually here for Pesach, it will be the first Pesach in my life that I won’t have a Pesach store to go to to buy my supplies,” Fisher said. “While it’s not an ideal situation, the prospect of sharing Pesach with the friends and Jewish community that we’ve built here over the past few months is exciting.”

Others now face the unusual prospect of conducting the communal meal alone. Efrem Epstein, who lives alone in Manhattan, planned to join with friends or family, or a synagogue, for the seders. Now he’s wondering whether he’ll end up hiding the afikomen and finding it himself.

“Throughout the Haggadah, we read about many accounts of our ancestors, whether it be in Egypt or whether it be hiding in caves or any other times, that are going through some very challenging times,” Epstein said. “I’m an extrovert. I like being around people, but I also know that there are sources saying that if one is doing seder by them-selves, they should ask the Mah Nishtana of themselves. If that’s what I have to do this year, I accept it.”

If people are limited to small or virtual seders on the first nights of Passover, they might have a kind of second chance, said Uri Allen, associate rabbi of Temple Beth Sholom in Roslyn, New York. Allen is in a group of rabbis pondering the renewed relevance of Pesach Sheni, literally “Second Passover,” a day that comes exactly a month after the first day of Passover. In ancient times, Pesach Sheni was a second chance to make the paschal sacrifice for those who had been unable to on the holiday itself.

Allen said that in any event, Jews should have a seder on the first night of Passover. But if they are looking for a chance to make a communal seder with friends or family, then depending on the coronavirus’s spread, they might be able to do so on Pesach Sheni – without the blessings or dietary restrictions.

“I’m imagining both for my family and also probably many other families who are used to a certain kind of seder, larger gatherings and things like that, that probably won’t happen a lot this year,” Allen said.

“I would definitely encourage and advocate, if your seder got interrupted or disrupted because of the coronavirus, why not have the seder that you wanted on Pesach Sheni – provided everything is clear and people can resume some sort of normal life.”

He wanted to encapsulate Beijing’s Jewish community in a Haggadah. Then COVID-19 came along.

By Alan Grabinsky

(JTA) – Unlike Shanghai or Hong Kong, which received Jews fleeing from World War II, Beijing does not have a robust Jewish history.

In the words of Joshua Kurtzig, former president of the Reform congregation there, the massive Chinese capital is a “very transient city,” especially for Jews – meaning that many pass through without putting down generations of roots.

Some 1,000 Jews now live in Beijing among its 20 million residents, and the congregation, Kehillat Beijing, has no permanent clergy.

“There are no Jewish tours here,” said Leon Fenster, 33, a London-born artist who is active in the Beijing Jewish community.

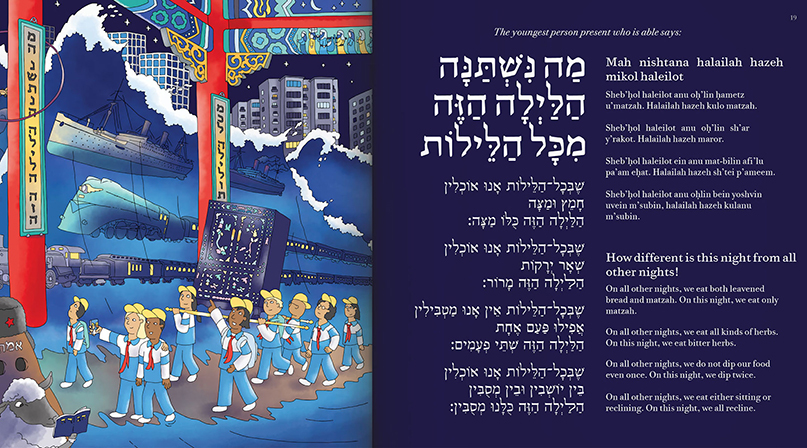

In an attempt to give the community some defining character – and intertwine it with the city’s millennia of rich history – Fenster has illustrated a Beijing-themed Haggadah in which the Exodus story takes place in the modern-day capital. The images are lush and full of meaning in both the Chinese and Jewish cultural contexts.

Fenster planned to inaugurate the Haggadah by using it to lead a massive seder in Beijing, but the rapid spread of the coronavirus, which is keeping all of China under lock-down, has complicated the effort.

After the outbreak picked up steam, Fenster traveled to Taiwan, which is seen as a safer territory because of its effectiveness so far in containing COVID-19. The Beijing community, according to Fenster, will not celebrate a physical seder this year.

Fenster has been interested in illustrating the essence of the Jewish Diaspora since he was in college. Trained as an architect at University College London, he won a Presidential Medal Award given by the Royal Institute of British Architects in 2014 for his drawings on how synagogues should reflect the Jewish diasporic condition. In 2015, he moved to Beijing as a scholar in residence at Tsinghua University, where he drew his first non-architectural drawing: a Haggadah concept.

He laid this idea aside and continued painting hypertextual drawings depicting life in the city, eventually exhibiting works in galleries in Beijing, the United Kingdom and Israel. But the idea for a Beijing Haggadah returned as he came to experience the transient nature of the Beijing community firsthand.

“There is a Diaspora of Beijing Jews who moved out of the city and think of China as a place where they found their Judaism,” he said.

Kurtzig, now the president of Kehillat Shanghai, echoed that feeling.

“You feel like a minority because you’re not Chinese, and then feel like a minority be-cause you’re Jewish,” he said.

The 180-page Haggadah is written in Hebrew, English and Chinese. According to Fenster, he needed to be careful not to incorporate too much Chinese because the government could see the project as proselytizing, which it does not permit.

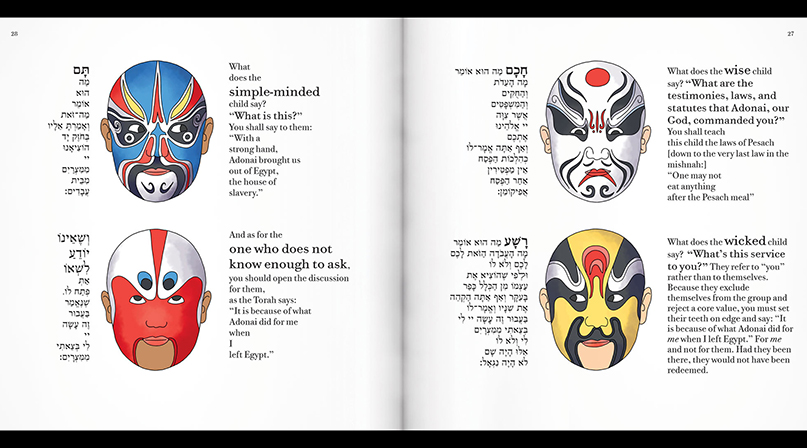

The book situates landmarks and cultural markers of the city in the myth of the Exodus. Jews walking through the parted Red Sea are dressed like Beijing schoolchildren. The Four Children wear different Beijing opera masks – an ancient custom born in the city – that designate certain character types.

“The more you know Beijing, the more this will have an emotional meaning for you,” he said.

With 40 to 50 core members, Kehillat Beijing’s Reform community (Chabad only opened a branch in the city in 2001) is made up of expatriates from the United States, England, Australia, Canada, France and the United Kingdom. Members lead the prayer services. Passover is one of the biggest events, Fenster said, drawing more than 80 participants to seder and taking place in the congregation’s main venue, a ballroom of a social club.

Kehillat Beijing was established by an American businesswoman, Roberta Lipson, who came to Beijing in 1979 with an MBA from Columbia University. She would go on to found the Chinese hospital company United Family Healthcare and become its CEO. She’s now married to Ted Plakfer, the Beijing bureau chief for The Economist.

One of the group’s first communal events was a Passover seder, Lipson has written, at the city’s Foreign Service International Club. Members had to teach the club’s kitchen staff how to make gefilte fish.

Over the years, Lipson has established a warm relationship with the more Orthodox Chabad community that has moved into the city.

“I appreciate that people now have a choice of how they want to approach Jewish observance and prayer. Kehillat Beijing exists for those who come from a liberal, conservative, reform, reconstructionist approach and for the many ‘mixed families,’” she wrote for the website of the Jerusalem Unity Prize. “On the other hand, there are now many people who live in or frequently visit our city who are more comfortable at Chabad services. We all celebrate the diversity we share and find it fulfilling that there are options.”

The Haggadah project was sponsored by Stephen M.L. Cohen and Carol Fishman Cohen in memory of their son, Michael H.K. Cohen, who was involved with Kehillat Beijing and the Beijing Moishe House but died of suicide upon his return to the United States. The news sent shockwaves across Beijing’s Jewish community, said Fenster.

In one of the Haggadah images, Fenster drew Michael seated with Roberta and other local leaders at a seder table.

Fenster originally wanted to print 600 copies of the book in Beijing. But now he will lead a seder in Taiwan and inaugurate the Haggadah in an online forum. He’ll wait for the seder next year to do a real celebratory launch in Beijing.

“This will be a soft inauguration,” he said. “I’m excited about the idea. It will be nice for people, wherever they are in the world.”

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger