Shemini Atzeret is the holiday that follows immediately after the seventh day of Sukkot. Literally, Shemini Atzeret means “the eighth [day] of assembly.” The Torah designates this day as one of solemn assembly and prohibits labor.

In 2019, Shemini Atzeret begins at sundown on Monday, Oct. 20 and ends at sundown on Tuesday, Oct. 21. Simchat Torah immediately follows on Tuesday evening, and ends on Wednesday, Oct. 22.

Shemini Atzeret serves to conclude the holiday of Sukkot, although it technically stands as its own festival. In this way Sukkot begins with a yom tov (full holiday) and ends with a yom tov, while the days in between are the intermediate festival days (hol ha-mo’ed). Thus, the concluding holiday acts as a transitional day leading the worshipper out of the various levels of meaning inherent in Sukkot. The community assembles again to end the festival.

Jewish tradition has attributed various meanings to Shemini Atzeret, to which the Torah offers little justification. One example: The Rabbis say that the festival is God’s way to retain closeness with the Jewish people for a little while longer; Sukkot was a pilgrimage festival in which the nation gathered in Jerusalem during Temple times. The addition of Shemini Atzeret delayed their departure briefly.

The medieval sage, Rashi, understood Shemini Atzeret through a parable. Imagine a king who had invited his children to dine with him for seven days, but after a week begged them to stay one day longer. In this parable, God is the king and the Jews are the children. The banquet is Sukkot (celebrating the bounty of the harvest) which is stretched on for one extra day, Shemini Atzeret. It’s a rather lovely description of God’s relationship to the Jewish people.

It is customary to read the book of Ecclesiastes (Kohelet) on the Sabbath of the intermediate days of Sukkot. However, should there be no Sabbath on those days, Ecclesiastes is read on Shemini Atzeret. The theme of Ecclesiastes is very fitting for this holiday, as it emphasizes that all of nature is a closed system, and life itself can appear to be a futile journey.

The dynamic that fights off this sense of futility is the individual’s relationship with God. The nature themes and the spiritual musings found in Ecclesiastes mirror many of the themes of Sukkot, and we are reminded of them once again on Shemini Atzeret as we close the holiday. The prayer for rain recited on Shemini Atzeret provides a further thematic link with nature and perhaps hints at the ancient Sukkot water libation festival.

In Israel and in liberal Jewish congregations Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah are celebrated on the same day. In all other congregations, Simchat Torah is celebrated the day after Shemini Atzeeret, following the tradition of adding an additional day to festivals in the Diaspora.

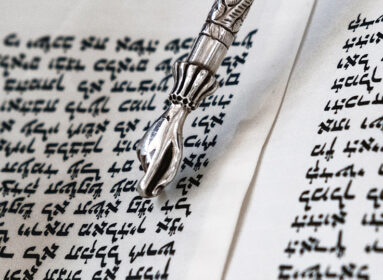

Simchat Torah – which roughly translates to “rejoicing with the Torah” – is a holiday that occurs at the same time, but has an entirely different focal point. On this festival, the Jewish community ends its cycle of public Torah readings and immediately begins the next cycle of readings. All the Torah scrolls are removed from the ark in the synagogue, and the bimah or sanctuary is circled seven times (or fewer, depending on the congregation’s tradition) in a festive procession known as a hakafot. The congregation celebrates this completion and beginning by dancing and singing with the Torah scrolls.

On Simchat Torah the ending of the book of Deuteronomy is often read several times, since it is traditional to offer an aliyah to all those who wish to participate. The term used for this aliyah is hatan Torah, the “bridegroom of the Torah.”

Immediately following this aliyah, the first part of Genesis is recited, and this aliyah is called hatan Bereshit, “the bridegroom of Genesis.” [Egalitarian congregations may also offer a parallel aliyah for the kallah, the “bride of the Torah” or the “bride of Genesis.”] These terms speak of the perceived relationship the Jewish people have with Torah study. The commitment to the Torah is likened to that of a marriage in which two parties are singularly committed to each other.

It is an intimate relationship that challenges the individual and defines much of his/her identity. The marriage symbolism in the relationship between God and the people Israel is also found in seven processions around the synagogue, calling to mind the tradition of a bride circling the groom seven times.

The cycle of readings, moving from end to beginning, mirrors the cycle of the hakafot, the circles walked around the ark. The entire image becomes symbolic of unending Torah learning. Unlike Shavuot, the holiday that celebrates the receiving of the Torah, Simchat Torah commemorates the community’s commitment to learning and its love of the Torah. Whereas Shavuot focuses on the burden of responsibility in receiving the Torah, Simchat Torah emphasizes the ecstatic joy of studying Torah. Simchat Torah reflects the rabbinic teaching that one studies Torah one’s entire lifetime and always finds new meanings within it.

The period of the High Holidays concludes with Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah. Beginning in the month of Elul and spanning Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot and finally Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, the High Holiday period encompasses many of the themes that are central to Judaism. Accountability, spiritual awareness, harmony within nature, individual and community issues all find a place within this time period and set the tone for the coming year.

This article is reprinted from My Jewish Learning (www.myjewishlearning.com).

Main Photo: “The Feast of the Rejoicing of the Law at the Synagogue in Leghorn” (Solomon Alexander Hart/The Jewish Museum)

Southern New England Jewish Ledger

Southern New England Jewish Ledger